Envisioning a New York Where Cycling Isn’t Just for Cyclists

At a panel sponsored by the American Institute of Architects last night, two of the city’s top transportation planners joined one of its hardest-working bike advocates to discuss how to make cycling a mainstream mode in New York.

The director of the Department of City Planning’s Transportation Division, Jack Schmidt, DOT Senior Policy Advisor Jon Orcutt, and Transportation Alternatives’ Caroline Samponaro each shared different perspectives on why NYC is well-suited for a boom in biking and how to make it happen. Hovering over the evening was the question of whether the city’s accelerating commitment to pro-bike policies will be matched by long-term public support and political will.

Schmidt brought a wealth of new data to the discussion. DCP recently completed two studies that highlight the potential to expand cycling, especially outside Manhattan. The first crunched Census numbers to examine what DCP calls "peripheral trips," commutes that don’t start or end in the Manhattan CBD. Though DCP began the study expecting to find common origins and destinations that might be appropriate for new transit routes, Schmidt said that isn’t what they found. "What rose to the top," he said, "was there are all these short trips that are good for biking."

Outside of Manhattan, he explained, most workers commute to the same borough they live in, and many go to the same section of the same borough. "If people are living close to where they work," he argued, "those are trips that are not suited to the automobile, that are not suited to transit; they’re suited to walking and biking."

Intra-borough commutes show a lot more walking and cycling, included in the light blue slices, but rarely less driving. Image: NYCDCP

Intra-borough commutes show a lot more walking and cycling, included in the light blue slices, but rarely less driving. Image: NYCDCPWhile DCP’s research shows that New Yorkers are already making a significant number of these short commutes by walking or biking, Schmidt concluded that there’s plenty of room for this percentage to grow. Commuters who stay within their home borough drive at similar rates to commuters with longer multi-borough trips. There is significant untapped potential, Schmidt said, to convert those short car commutes to bike commutes.

Orcutt reinforced this point, citing household travel data showing that 56 percent of all car trips in New York City are less than three miles long.

Schmidt also discussed the potential to integrate cycling with the transit system. "For most of us, the bicycle has a pretty limited range," he said, but as a link to transit, it can help almost any New Yorker get where they’re going. Already, he said, 29 percent of commuting cyclists connect with another mode, usually transit.

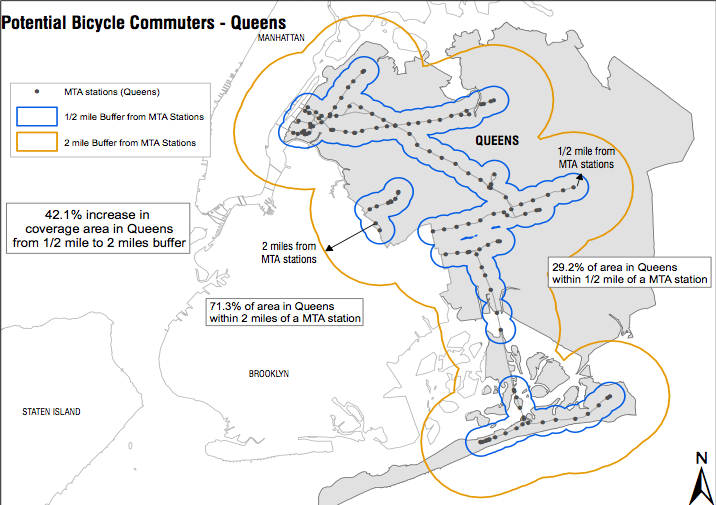

If the city built on that, biking could dramatically expand the reach of the city’s transit system. A DCP report called "Bike+Ride" found that while only 29.2 percent of Queens is within the half-mile walking distance of a subway station, a full 71.3 percent is within a conservative biking distance of two miles. In the Bronx, 56.6 percent of the borough is within walking distance to the subway, while 95.4 percent is within biking range. If New Yorkers could easily bike to the nearest station, the subway system wouldn’t just serve most New Yorkers; it could serve almost all of them.

You can’t walk to the subway from most parts of Queens. But unless you live on the eastern edge, it’s a short bike ride to a station. Image: NYCDCP

You can’t walk to the subway from most parts of Queens. But unless you live on the eastern edge, it’s a short bike ride to a station. Image: NYCDCPBut if you can’t park your bike at the subway, you can’t bike there. At 95 percent of Bronx stations, DCP found no bike parking at all. In response, DCP looked at how parking could best be added near transit. At the crowded DeKalb Avenue station in Brooklyn, for example, they recommended installing vertical bike parking.

While Schmidt focused on the types of potential bike trips, Orcutt discussed who would make those trips. Using a framework developed in Oregon, Orcutt argued that while a tiny pool of "strong and fearless" people will bike regardless of infrastructure and a slightly larger set of "enthused and confident" New Yorkers are using painted lanes, the bulk of the city is "interested but concerned." These potential riders use the greenways and are starting to use the new protected lanes, a point Orcutt illustrated by showing photos of young kids riding their bikes along the new Prospect Park West lane.

One way to lower some of the barriers that confront "interested but concerned" New Yorkers is to open up cycling through a public bike-share program. Advancing his slideshow to a picture of a yellow-taxi branded bike-share kiosk, Orcutt received instant applause. When Paris installed its bike-sharing program, he said, cycling quadrupled in one year.

In the Q&A session, Orcutt suggested a readiness for bike-sharing inside city government. When asked whether cycling infrastructure is now safe enough to launch bike-share in New York, he said: "In some parts of the city, yes. In some parts of the city not so much. But in a couple of years, you could have it." Orcutt also argued that new international examples could show that ubiquitous bike infrastructure isn’t a prerequisite for bike-share. "London certainly has far less than Paris or New York in their bike-sharing area," he said.

Samponaro agreed that bike-sharing could be a game-changer for the perception of cycling in New York. "You’re talking not just about mainstreaming biking in a city," she said, "you’re talking about making biking public transportation."

Of course, making cycling a mainstream mode is also a cultural and political question. The biggest hurdle to expanding cycling in New York isn’t feasibility, said Schmidt. "Buy-in," he said, is the challenge.

Orcutt agreed that the greatest challenge will be "the battle for public opinion over whether bicycles belong in public policy or not. The test will be in 2014, when we have a new administration. Then we’ll find out who won that battle."

Cycling is more likely to win that battle, argued Samponaro, if cyclists contribute to a culture of order on New York City’s streets. Anti-cyclist anger, she said, is a manifestation of a general feeling that streets are chaotic. New Yorkers see everyone on the street disregarding the rules and ask, "How can we handle anything more?" By enforcing traffic laws for both drivers and cyclists, and implementing traffic calming devices, the conflict over cycling could be toned down, she implied.

With leaders from both DOT and DCP on stage, a few other interesting insights into the future of cycling and transportation policy in New York were revealed as well:

- DCP is currently developing their own routing software for bike trips, to compete with Ride The City or Google Maps. Called NYCyclistNet, the program would add new lanes faster than its competitors, include all public and private bike racks in the city, and perhaps most importantly, have a feedback option that allows users to make recommendations directly to city government.

- When asked about reforming New York’s off-street parking policies, Schmidt told the crowd to "bear with us," calling the issue "something we’re very concerned about." The department is currently undergoing a major review of its parking policy. Orcutt urged those concerned about the issue to work for its inclusion in next year’s update of PlaNYC, the outreach meetings for which begin this winter. "If not everyone [in city government] got the memo," he said, "there’s time to work on that."

- The MTA is getting friendlier towards bikes, said Schmidt. "For the longest time, they were really opposed to bikes inside their system," he explained. "Now they’re realizing that bike riders are their customers, too." Though warning not to expect anything in the short term, Schmidt told cyclists that the agency is becoming a more enthusiastic partner on the issue.

- When an audience member asked a question about traffic enforcement, the panel’s organizer stepped in, saying that "we wanted to get an enforcement person here." Added Orcutt: "It’s emblematic that you don’t."

- Asked about Parks Department policies that make Central Park an obstacle for cyclists trying to go crosstown, Orcutt revealed that there is discussion of creating a two-way bike route across the park along 72nd Street.