With Congestion Pricing, Saving Time Trumps Reducing Pollution

A prime target of the early environmental movement was car tailpipes. And for good reason. Put a human in a garage with a running auto in the old days, and he or she would pass out within minutes and be dead in an hour. Run a few million vehicles daily in New York or Los Angeles, and the toxic air would kill thousands each year and sicken many more.

But as the saying goes, that was then, this is now. Cars now on the road are 30 to 50 times less polluting than in 1970. True, there are more cars being driven more miles, but even with a tripling of VMT (vehicle miles traveled), U.S. passenger vehicles today are probably putting out only a tenth as much air pollution as they did on the first Earth Day. Even trucks and buses are getting cleaned up. Thanks to advocates like NRDC attorney (and local transportation advocate) Rich Kassel, diesel fuels and engines are in a decade-long transition from dirty to clean. (Stood behind a soot-belching NYC Transit bus lately? Me neither.)

Old notions die hard, however. Witness the asthma mantra before and during the unsuccessful 2007-08 campaign for Mayor Bloomberg’s congestion pricing plan. And just last week, the New York Times picked up the same cudgel in a New Year’s Day editorial:

The latest report on air quality from the city’s health department is especially alarming: it showed unhealthy levels of pollution in high-population areas throughout the city. Mr. Bloomberg should revive his fight in Albany for some form of congestion pricing.

A classic non sequitur: Yes, pollution is still at unhealthy levels; yes, congestion pricing is needed; but the link from the first fact to the second is tenuous.

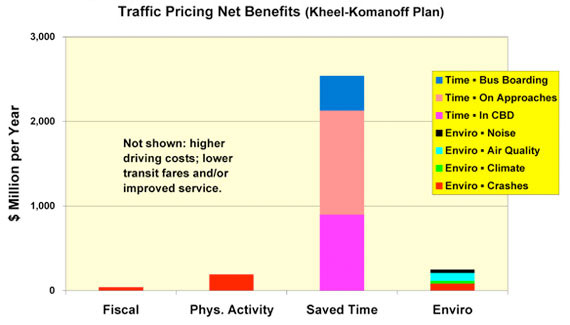

To see why, please pay a visit to the Balanced Transportation Analyzer. I’ve set the BTA with “Kheel-Komanoff” inputs: a variable $3-$6-$9 toll to drive into the Manhattan Central Business District (less on weekends and holidays), a 33 percent taxi fare surcharge, and revenues dedicated to make subways and buses cheaper and free, respectively. But my point holds with almost any cordon-based congestion pricing plan:

Direct environmental benefits from congestion pricing — fewer crashes, less traffic noise, reduced carbon emissions, and cleaner air — are worth only one-tenth as much, combined, as the time that users of autos, trucks and buses will save getting around. The air pollution benefit alone, computed as the monetary value of fewer illnesses and deaths, is less than $100 million, even counting the reduction in stop-and-go driving inside the CBD, where traffic speeds during the morning and evening peaks are predicted to increase 20-25 percent. In contrast, the projected time savings are worth $2.5 billion, or roughly 25 times as much as the improvement in air quality.

How can this be? The 25-fold difference between time benefits and air benefits isn’t from cooking the numbers. I’ve programmed the BTA with conservative estimates of the “value of time” and liberal estimates of the health value of curbing soot and ozone-forming gaseous pollutants. (I doubled the dollar-per-ton values that the hawkish California Air Resources Board uses to screen antipollution measures.)

Rather, there are three reasons that in almost any congestion pricing plan, whether Kheel-Komanoff or Bloomberg or Ravitch, the value of the time savings will dwarf the air quality benefits:

- On a regional basis, congestion pricing eliminates only a small percentage of VMT. Ditto, tailpipe emissions.

-

Emissions from present-day cars (and, increasingly, trucks and buses) are low and trending lower. Thus, the vaunted improvements in traffic flow won’t eliminate much car exhaust, because there isn’t much to begin with.

-

Time savings from tolling gridlocked roads rise geometrically with congestion. A given percentage increase in speed saves six times as many minutes when the base speed is 5 mph as when it’s 30 mph. Considering that slow speeds also imply high volumes, congestion pricing is practically ordained to generate big time savings — particularly if the tolls are varied by time of day and day of week.

The lesson for congestion pricing advocates is clear: give the "green" angle a rest. We’re not in 1970 anymore. (If per-mile emission rates hadn’t changed since Earth Day, the air quality benefits would be some 40 times greater, equaling or even surpassing the time savings.) Clean air no longer provides a powerful rationale for congestion pricing.

From a cost-benefit standpoint, the overwhelming reason to adopt congestion pricing in New York City — in addition to providing a vital new revenue stream for public transit, of course — is to enable people stuck in traffic to save time.

Curing aggravation, not asthma, should be motivation enough for congestion pricing.