High Hopes — And Higher Standards — for Bloomberg 3.0

Our series on the next four years of NYC transportation policy continues with today’s essay from Joan Byron, Director of the Pratt Center for Community Development’s Sustainability and Environmental Justice Initiative. The Rudin Center for Transportation Policy recognized Byron’s work at the Pratt Center with the 2009 Civic Leadership Award. Read previous entries in this series here and here.

In New York political time, four years passes fast. But hey, in Bogotá, Enrique Peñalosa was limited to a single three-year term as mayor, during which he built dozens of new schools and libraries, converted a golf course to a public park, laid down 100 miles of bike paths, and of course, built the Transmilenio, the system against which Bus Rapid Transit aspirants worldwide are measured.

Bogotá built out most of the TransMilenio system during Enrique Peñalosa’s single three-year term. Photo of estación Jiménez: Joan Byron.

Bogotá built out most of the TransMilenio system during Enrique Peñalosa’s single three-year term. Photo of estación Jiménez: Joan Byron.What can get done under Bloomberg 3.0? The answer depends on lots of things, some of which are now in short supply. Money, for instance. The next several NYC budget years will be hard on everybody, and really hard on the people and neighborhoods who were bypassed by the economic boom, and who’ve since been battered further by the recession depression. In this environment, will City Hall keep shoveling cash into sports stadia and shopping malls? Will it continue to count on the real estate market to throw off a few crumbs of affordable housing? Or will we seize the moment and use zoning and subsidies as tools to shape the city we want, instead of simply facilitating the worst instincts of developers?

Transportation policy under Bloomberg 3.0: Money’s not the problem

The next set of BRT routes needs to fearlessly go where no bus has gone before.

The good news is that some of the most effective transportation investments we can make in the next four years are also the most affordable. Implementing a full-featured and far-reaching Bus Rapid Transit system won’t require either New York City DOT or the MTA to come up with a big new pile of capital dollars. Good BRT, like good pedestrian and bike infrastructure, does cost money, but at a pay-as-you-go level, rather than demanding multi-billion dollar upfront investments that can take decades to deliver results. It costs millions, not billions, and it can be up in running in months, rather than decades.

And real BRT will be transformative. New York City today is home to 758,000 workers who travel over an hour each way to reach their jobs. Two-thirds of these folks are going to jobs where they earn less than $35,000. That’s not a coincidence — look at a map, and you’ll quickly see that the places poor and working-class people can afford to live are those least well-served by the subway system.

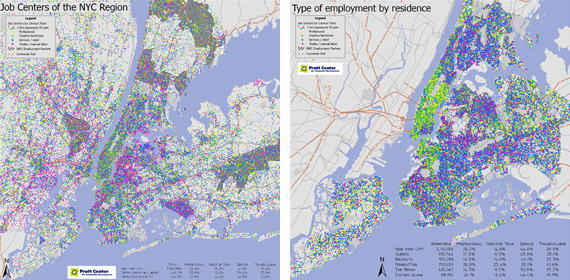

Click to view full versions of the Pratt Center’s maps depicting where NYC jobs are clustered, and where workers in different sectors live.

Click to view full versions of the Pratt Center’s maps depicting where NYC jobs are clustered, and where workers in different sectors live.Jobs in health care, retail, construction, and manufacturing are spread across the city and the region, as opposed to the high-wage sectors concentrated in the Manhattan core. Manufacturing and distribution jobs are especially isolated from the transit network. Talk to workers (or employers) and you’ll hear about dollar vans, livery cabs, employer-paid shuttles, and other work-arounds for a transit system that bypasses these vital centers of living-wage, blue-collar employment. The hospital belt in Central Brooklyn — SUNY Downstate, Kings County, Kingsbrook, and Brookdale — employs 18,250 New York City residents. More than 35,000 New Yorkers work at JFK airport, but most of them drive there, because the transit connections are expensive and inefficient.

So here’s the good news. DOT and the MTA are on the right track, and they’re picking up speed. Jay Walder really understands the importance of buses — with good reason, since much of London is built at densities comparable to Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, with subway coverage to match. In London, buses are now a primary mode, prioritized by street space allocation, enforcement, and technology. DOT and the MTA have stated their mutual commitment to making New York’s bus system perform for its 2.3 million daily riders. Last year, DOT Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan announced that the agencies would complete their 5-route "BRT Phase 1" by 2013, and simultaneously develop plans for "BRT Phase 2." These additional 8-10 routes would combine with Phase 1 to create a citywide network connecting underserved residential neighborhoods and employment centers, shortening at least some of the city’s worst commutes. This summer, the agencies launched a workshop series that was a great first step in engaging affected communities in the earliest steps of their planning process for BRT Phase 2.

The key ingredient: Vision

Aside from a relatively modest level of investment, what we need now is vision. There’s no shortage of that at either DOT or the MTA. These are the folks who brought us the Bx12, the modestly-named "Select Bus Service" that has chopped 20 minutes off thousands of Bronx commuters’ trips, and done so with little more than ingenuity and duct tape.

DOT, the MTA, and advocates need not only to get boots on the ground, but to get listening ears into neighborhoods. Pay attention.

We need more of that. The next set of BRT routes needs to fearlessly go where no bus has gone before. Its physical design standards have to maximize BRT benefits, not only for riders, but for pedestrians and cyclists. It must extend the blessings of a one-seat ride across boroughs and bridges (notably the Williamsburg Bridge, instead of dumping B44 riders onto the already overcrowded J/M/Z trains on the Brooklyn side). And the next Phase 1 routes — First and Second Avenues in Manhattan, and the B44 corridor in Brooklyn — need to be built with more of the features that mark BRT as a truly new "third mode," incorporating design features that will not only improve bus performance, but make streets safer for pedestrians and cyclists by physically taming traffic.

But even the clearest BRT vision will be gridlocked without political support, and the will within the administration to build it. What we also need, and what may be in short supply for Bloomberg 3.0, is more than political capital (this administration is nothing if not savvy about transactional politics). Far-reaching changes to our streets and transit system will require the kind of support you grow from scratch, by getting out there, talking with the people you know you’re trying to help, but who may have competing priorities, different perspectives and past experiences with this administration that have fueled their skepticism.

As we learned in working on congestion pricing, you don’t surmount those barriers by trying to steamroll legislators with artificial deadlines, or by herding "advocates" (yes, Streetsblog readers and contributors, that would be us) around 250 Broadway and the Capitol to deliver a consultant-crafted message. I only know one way to build the kind of support that both BRT and the transformation of our streets will need. It’s basically Organizing 101: You meet people where they are. If legislators don’t have our issues at the top of their list, it may well be that their constituents are more worried about their housing, their jobs, and their kids. Dissing and dismissing electeds who don’t put "our" issues at the top of their agenda is not just unhelpful — it widens the class and racial gap between an "elitist" Livable Streets Movement and everybody else.

New Yorkers have just elected a feisty new class of City Council members — and re-elected incumbents — who are likely to be less pliant than their predecessors. This could be the best thing that ever happened for equity in the causes of transportation and livable streets, if we can re-connect with the social and environmental justice roots of our work, and shed some of our elitist baggage.

DOT, the MTA, and advocates need not only to get boots on the ground, but to get listening ears into neighborhoods. Pay attention. If the arguments of pols demagoguing against good initiatives from the agency gain traction, it’s coming from someplace. Perhaps it’s a response to past failures to deal with pressing neighborhood issues — like truck traffic, hideously bad local air quality, and so on. Get out there, learn about what people are living with, and meet them where they are. Work with local organizations that are credible because they’ve been listening to their communities, and don’t treat community-based organizations as messengers to "help us get the word out," but as partners whose input adds value and whose concerns get addressed.

I don’t know what the internal budget and management constraints might be, but my fondest hope for BRT, as well as for the expansion of safe space for the vast majority who walk, bike, and take transit, is that NYC DOT will find the means to double, triple, or quadruple the number of field and office staff who work in these essential areas, and deploy these folks in the neighborhoods where most New Yorkers live, where people are being run over by cars and trucks, where kids can’t play for fear of asthma attacks, where workers are waiting for packed buses. In short, where people are literally dying for the kind of attention that’s been paid to high-profile areas in Midtown. When organizations from those neighborhoods step forward with both their problems and their ideas for solutions, they shouldn’t be told to wait for their turn, which will be sometime next year.

In short, to NYC DOT under Bloomberg 3.0: Keep doing what you’re doing. But do it faster, cover more ground, and devote acute attention and resources to the most underserved communities in the city. If you do it right, you can be assured that those communities will have your back.