Let’s Chop Up Superblocks

Forest City’s Atlantic Yards project would create two massive superblocks in Prospect Hts., Brooklyn

Portland, Oregon, which has ascended the ranks of cities judged most walkable, bikable, and urbane, benefits mightily from its small 200-foot square blocks, which provide businesses more street frontage and people more streets on which to bike, cycle and walk. These short blocks did not create Oregon’s and Portland’s growth management and pro-transit policies, but they gave them terrain on which these policies could take root.

Contrast that to Salt Lake City. Its founder Brigham Young for some reason opted for one of the widest urban grids anywhere. (I’ve read he wanted teams of cattle to be able to turn around?) Its streets are laid out in a grid where each blocks is 660 feet square – which means that nine Portland blocks to fill up one Salt Lake superblock. This makes getting around Salt Lake City on foot very difficult, as I can personally attest.

New York City is somewhere in the middle, at least in Manhattan. Its numbered streets are set at a pedestrian friendly 200 feet apart while its avenues are set at a pedestrian unfriendly 800 feet apart, except where broken in two by Lexington, Madison or other mid-grid streets. This deficiency has long been noted, so if anything the city should have a set policy creating new streets when possible, and so to create shorter, more pedestrian friendly blocks.

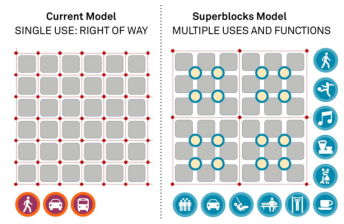

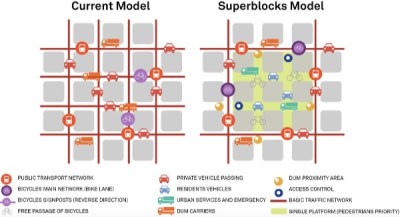

But that is not the case. Instead the city and state often encourage one of the deadest institutions, the Superblock. Not content with blocks that are too large already, the city and state often team up to create even bigger blocks, and not even pedestrian friendly versions of those.

What exactly is a superblock? This term came into vogue in planning circles more than a half century ago to describe the then fashionable idea of demapping older street grid and creating one large blocks where before many blocks had been. It was thought that the old small blocks were outmoded, and did not fit a car-friendly culture. Jane Jacobs, among others, fired a stake into the heart of this idea, and now, theoretically at least, the superblock is dead. There are few defenders of it — theoretically.

But practice is different than theory. Let’s look at a few examples.

There’s the Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn. While there are a lot of reasons to criticize this project, starting with the process that seemed to reverse the normal way development of a public parcel should proceed. But when you get down to urban design of the plan itself, it has entirely too few streets. Not only does it de-map some existing ones, it doesn’t pick up the possibility of creating new ones so that this big area could be divided into smaller, pedestrian friendly blocks.

The Hudson Yards Development on the Far West Side of Manhattan is still evolving and it’s far from clear what exactly will emerge there. But most of the proposed plans submitted by developers for the new area atop the West Side Rail Yards show towers set in parks or plazas. They seem more appropriate to an Edge City outside Dallas than in a dense urban city. Only the Brookfield plan, in its words, "honors the Manhattan street grid" by drawing several new streets across the site, and puts an emphasis on urban style buildings that front on streets.

Brookfield’s Hudson Yards project plan essentially maintains Midtown Manhattan’s street grid.

Why do developers haul out the superblock so quickly when designing current projects, and why do public officials let them, despite its near death in academic circles?

One common answer these days is terrorism concerns. Setbacks for more prominent buildings are often larger now, to allow for the placement of bollards and other protective measures. But there is a certain lack of logic here. After all, most New York City buildings do not have enormous setbacks from the street, so pushing that for newer buildings hardly deprives a terrorist of potential targets.

A stronger explanation to me lies in finance and issues of political power. Large concentrations of money affect development in New York City disproportionately, and such large concentrations of money often favor having large concentrations of land to work with. While it may be a disservice to the city to have a large, island-like superblock – traffic flow is disrupted, walking and bicycling trips are made more difficult — to the developer, a superblock allows for wide floor plates, campus-like settings and a level of land use control that would not otherwise be possible. And since the government sector is weak, large developers often end up doing what suits them first, not the public.

I’m not expecting to get rid of all superblocks. But it is a fair question whether the city should make creating a pedestrian friendly city of short blocks with buildings close to the street a priority. We have the most pedestrian oriented city in the country, but too often we chip away at its essential attributes in this regard, rather than seeking to add to them.

Photosim by Eric McNatt and Jason Lee for New York Magazine.