Taxi Surcharges and Congestion Pricing — They Go Great Together

The surcharge on NYC medallion taxi fares that took effect this month is a bit like a bases-loaded groundout that scores a run but kills a big inning: It does some good, but a ringing base hit could have done a lot more.

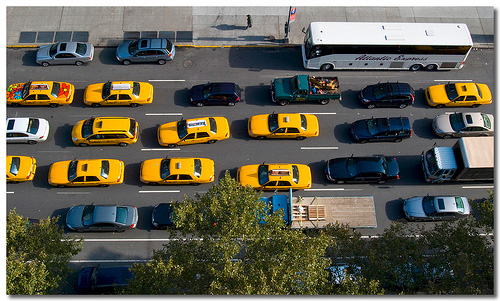

Congestion pricing paired with a significant taxi surcharge would speed cab trips and boost Manhattan’s transit funding contribution. Photo: Bill in STL/Flickr.

Congestion pricing paired with a significant taxi surcharge would speed cab trips and boost Manhattan’s transit funding contribution. Photo: Bill in STL/Flickr.The good, in this case, is a new pot of money for the financially strapped MTA: the 50 cent-a-ride surcharge is expected to raise $80 to $85 million a year according to transit officials, a figure confirmed by inputting the surcharge into the Balanced Transportation Analyzer (BTA) pricing model. While that will barely cover one percent of the MTA’s budget, it will help patch the authority’s deficit and sustain essential services like subway car cleaning and system maintenance.

A side benefit is that the discouragement of taxi use due to the surcharge should cause travel speeds in Manhattan to rise, saving time for car and truck drivers and bus passengers. With some taxi trips switching to subway or bus, transit farebox revenues will go up as well. But the surcharge is so slight — around 5 percent of a typical fare — that these gains will barely be perceptible: a mere 0.1-0.2 percent rise in Manhattan travel speeds and a $2-$3 million-per-year rise in transit revenues, according to the BTA. And any increase in taxi cruising to make up for the lost fares would cut into the minuscule improvement in traffic.

While the press bewails the surcharge’s impact on taxi users, the people likely to suffer the most are the drivers, who on average can be expected to turn 1½ to 2 fewer fares a week. Losing $20-$25 in weekly revenue may not seem like much, but it’s a bitter pill for drivers who can barely pay off their medallion leases as it is. Indeed, the taxi surcharge, enacted by the legislature as an afterthought to the "mobility (payroll) tax" last spring, may do to drivers what the new taxi credit card payment system reportedly has not: drive them to the wall, economically.

Does this mean that surcharging taxi fares to pay for transit is categorically a bad idea? Decidedly not. I’m prepared to argue that a taxi surcharge a good deal larger than 50 cents per ride is essential to the political and logistical success of congestion pricing. At the same time, congestion pricing is essential to making a taxi surcharge fair for taxi drivers and passengers. With, and only with, a cordon toll, will Manhattan traffic improve sufficiently that cabbies can book more fares per shift, not fewer. Moreover, the same speedup will enable users to save valuable time, partially compensating them for the surcharge and ensuring that the taxi sector stays robust.

To grasp these synergies, consider a variable toll to drive into the Manhattan Central Business District of $3 to $9 on weekdays and $2 to $4 on weekends, with the revenues used to cut transit fares roughly in half. Residents of Queens and Brooklyn would pony up 45 cents of every dollar in new toll revenue, because of tolls on the East River bridges. Manhattanites would contribute less than 7 cents of each dollar, less than residents of Nassau County, Staten Island and the Bronx, yet would reap most of the benefits of quieter and safer streets, cleaner air, and faster bus service.

Such a plan would be DOA in Albany. Indeed, I would argue that this very imbalance between beneficiaries and benefactors helped doom the Bloomberg cordon fee in 2008 and the Ravitch bridge tolls this year.

Now take the same toll plan and add a 33 percent taxi surcharge — yes, a one-third increase in the mileage rate, the waiting time rate and the "drop." Instantly, Manhattan residents — who comprise an estimated three-fourths of medallion taxi users — would see their payment share nearly quadruple to 25 percent. Brooklyn and Queens residents’ share would shrink from 45 percent without the taxi surcharge to 28 percent with it. The borough-inequity argument largely disappears.

Not only that, the taxi surcharge revenue, a cool $400-$500 million according to the BTA, could allow transit officials to eliminate bus fares. Free buses would be a particular boon in distant precincts where subway lines don’t reach. As well, the rise in the taxi fare would offset the fall in the "time cost" of taxi service due to the decrease in auto traffic, and keep new taxi trips from inundating the CBD. Total use of medallion cabs would stay roughly constant under this integrated plan, with the reduction in gridlock enabling drivers to handle an extra 15-20 fares per week without booking more hours.

As for the effect on taxi users, the BTA indicates that the integrated plan outlined here would add $2.16 to the price of the average CBD cab trip while shortening the ride by 1.8 minutes. In other words, passengers pay $1.20 per minute saved — a steep rate, for most of us, and it would be steeper for trips that venture outside the CBD, where the travel time savings would be smaller, percentage-wise. Even with a cordon toll, then, taxi surcharges can’t be sold to riders as an unalloyed win-win, although riders could help themselves by cab-pooling and prioritizing their taxi use.

Of course, taxi surcharges are still justified as a means of internalizing the "social delay" costs of vehicle traffic on congested streets. They’re most fair and effective, though, when coupled with cordon tolling.