DOT: We Don’t Have the Money to Carry Out Our Own ‘Master Plan’

The Department of Transportation’s long-awaited Streets Master Plan presents, as expected, a glossy vision of a New York bristling with new bike lanes, new bus lanes, cleaner sidewalks, more accessibility for the disabled and roadways freer of smoke-belching trucks.

It’s a shame the agency doesn’t have the money to implement it.

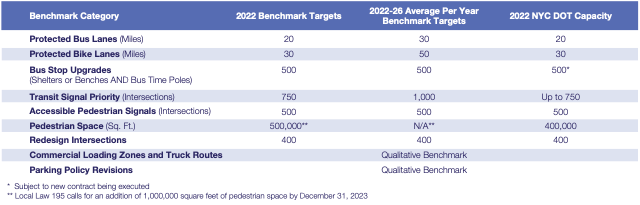

Three times in the 96-page document, which was released on Wednesday, the agency included the same graphic to emphasize (and re-emphasize) that it lacks the resources to meet the benchmark established by the Council when it passed the Streets Master Plan law in 2019.

Where the council law required the installation of 150 miles of protected bus lanes over the next five years, the DOT says it can only do 100. The council requirement of 250 miles of protected bike lanes in the same half-decade? The DOT says it can get to 150.

“I would be remiss not to mention that execution of this Plan will depend upon the continued availability in the years ahead of the financial, material, and human resources necessary to meet such ambitious objectives,” DOT Commissioner Henry “Hank” Gutman says in the introduction, echoing predecessor Polly Trottenberg’s concerns when her agency testified against the legislation that created the master plan mandate.

“Meeting these benchmarks — and the other key parts of this plan — will require increased staffing, funding, facility space, and new implementation strategies,” states the report, which includes this chart three times:

But pre-ordained lane mileage requirements does not a master plan make, the agency also argued.

“One key point is that counting location miles is not the only way to measure success,” the report states. “We will install bus lanes, bike lanes, and other helpful street elements where they will provide the most possible benefits — which may not always align with maximizing mileage or total units installed. This will affect our progress on the benchmarks, but will ultimately be better for transportation in New York.”

Instead of a comprehensive plan — with specific projects or those benchmarks clearly identified — this proposal is more like yet another call to arms to move the city away from decades of auto-centric street design and siloed processes around buses, bikes, curb management and pedestrian access.

“These are proposals, not final determinations, and we expect them to change as our planning work and the community outreach process progresses,” Gutman, who was not made available to reporters after the agency’s quiet release of the master plan at 4:44 p.m., wrote in his introduction.

So instead of the master plan many activists envisioned, this Streets Plan outlines a number of ideas, some recycled, some “transformative,” that the DOT (implicitly: Eric Adams’s DOT) can work on over the next five years. Among them:

- A “dramatic” expansion of automated traffic enforcement to include camera-based against parking in bike lanes, illegal turns and overweight trucks.

- Higher registration fees for larger and heavier passenger vehicles.

- A residential pilot for containerized trash in 2022 (which was supposed to be started already).

- “Major” transit capital improvements like bus rapid transit and working with the MTA on funding subway expansions (contingent on “a focused review of how to bring New York City’s cost in line with international standards”).

- Improving existing highly trafficked protected bike lanes with things like green wave signal timing or even widening them.

- Broaching the idea of government funding for Citi Bike: “increasing access to Citi Bike service for more New Yorkers may require a different financial model that includes government subsidy.”

- Installing accessible pedestrian signals at 500 intersections per year.

- Making the city’s cargo bike program (which is what, exactly?) permanent and expand enrollment in the program to 2,500 bikes

- Putting off tackling one of the central causes of congestion: bad curb management. “There is a need to carefully evaluate and balance the needs of the many other competing uses,” the report states in its section about parking. “Though there is no simple formula for doing this, we will endeavor to develop and apply consistent and reasonable guidelines for curb space allocation.”

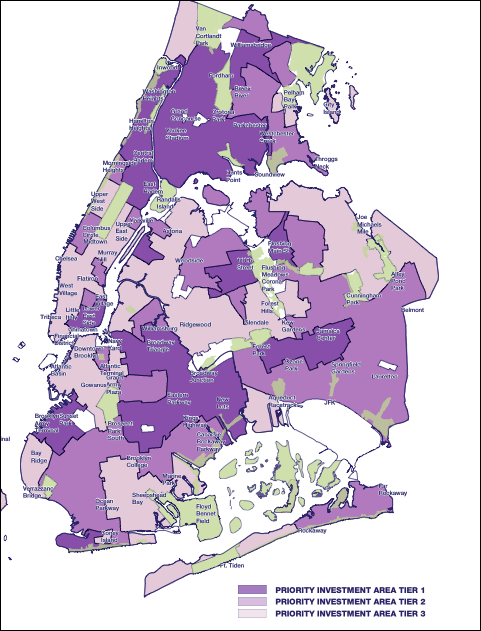

The DOT did say it would, for the first time, create a new metric for making sure projects are being undertaken equitably, creating “priority investment areas” that, activists have pointed, have been left behind in street safety improvements, resulting in higher injury rates in communities of color across the city.

“This plan establishes an overall framework for prioritizing transportation investments across the entire city,” the report states.

But even the mildest of street treatments in neighborhoods with next to no safety infrastructure get pushback from local legislators and community board leaders. The report gives a line to experimenting with different forms of community outreach but shies away from promising to treat community boards as advisory. Trottenberg once testified that the city would need a “re-envisioned public engagement model” to accomplish the goals laid out by the plan. But the report has nothing to offer there, meaning that community boards or local merchants or real estate developers can still be veto points after all.

In other words, the master plan is not a master plan at all — but just the latest guideline to be run up the flagpoles of various organizations to be shot down.

“We want more, not fewer, people to be aware of what we are planning and hope that they participate in the planning process, especially for projects that affect them directly,” the report states. “Different people will have different ideas about what is best for their community, and opinions within communities vary considerably.”

The report suffers under the weight of perhaps unfair expectations that were attached to it when it was pushed by City Council Speaker (and pre-pandemic mayoral frontrunner) Corey Johnson. He said the plan would give New Yorkers “a concrete vision of how we will reshape the city over the next five years and work toward our goal of making this a safer and more equitable place to call home.”

Still advocates were somewhat cheered, especially since incoming Mayor Eric Adams has already promised to do more bike and bus lanes than the DOT says it can handle.

“If you look at the policy agenda we put forward for the Adams administration, there’s a ton of overlap here,” said Transportation Alternatives Communications Director Cory Epstein. “But there’s an important value to having these ideas legitimized by the DOT rather than just coming from advocates on the outside. It shows these things are not just pie in the sky things that Oslo and London are talking about, it’s things that NYC DOT knows about and is talking about and now must make happen.”

But the report’s publication just one month before new agency leadership is expected to take over left one activist and seasoned city hand unimpressed.

“We don’t feel an urgency to comment on it until there’s a new commissioner next month,” said Bike New York Director of Communications and Advocacy Jon Orcutt.