BIKELASH: Powerful Pols Seeking to Block DOT’s East Flatbush Street Safety Plan in Pander to Drivers

A powerful Assembly Member in East Flatbush and an ally of the future mayor are trying to prevent city officials from making roadways safer in a majority Black neighborhood. But residents are pushing back, insisting that cyclists in the area are not invisible and deserve protection.

It’s a fight that’s come up since Assembly Member (and Brooklyn Democratic Party Chair) Rodneyse Bichotte Hermelyn and Community Board 17 Transportation Committee Chairman Roderick Daley — an appointee of Mayor-elect Eric Adams — came out in a full-throated opposition to a Department of Transportation effort to add some painted bike lanes to an injury-strewn neighborhood that has been an agency priority since at least 2017.

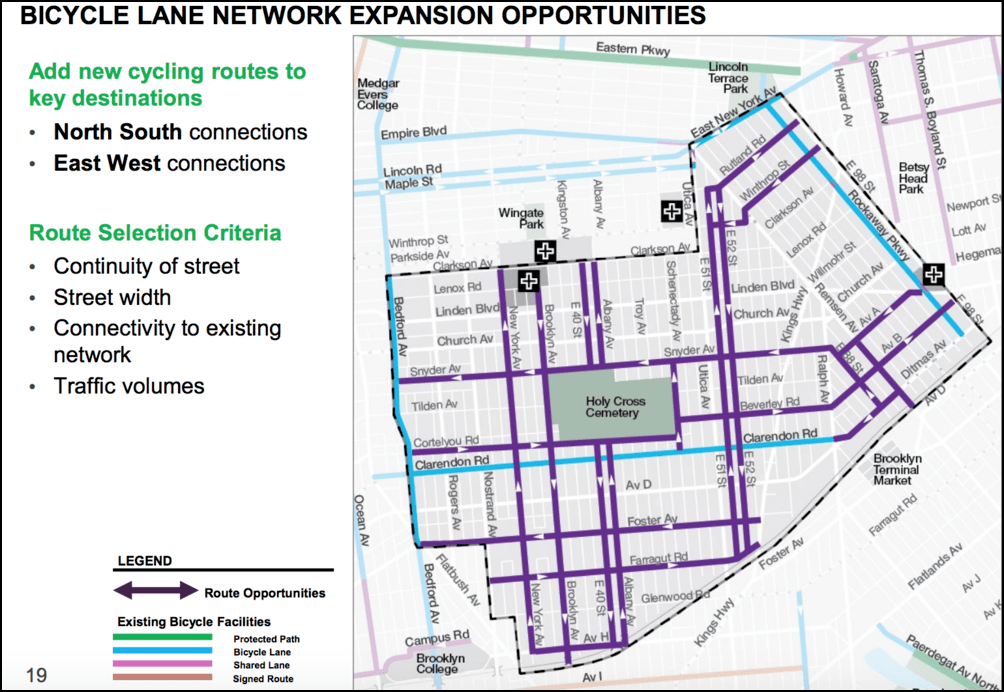

Right now, there are only three bike lanes in the district. Two run north and south (one on Rockaway Parkway on the eastern edge of the district and one on Bedford Avenue on the very western edge), and one east-west route across Clarendon Road between Bedford and Ralph avenues.

‘But people don’t bike here’

Under the DOT proposal, north- or southbound lanes would be added on New York, Brooklyn and Albany avenues and on East 40th, East 51st and East 52nd Streets, while east- or westbound lanes would be added on Snyder and Foster avenues; Farragut, Beverly and Rutland roads; and Avenues A and B. None of the painted bike lanes — repeat, none — would replace travel lanes or repurpose any of the neighborhood’s car storage spaces. The agency said it conducted months of in-person and online feedback the agency collected in the area, resulting in 800 responses, 300 of which came from face-to-face interviews.

But Transportation Committee Chairman Roderick Daley said he didn’t believe that the DOT’s survey effort was accurate because he spoke to people, too.

“I have done my own survey talking to people in the community about bike lanes,” said Daley, who was appointed to the board by Adams in 2014. “I have not gotten any positive feedback from anyone about the increase of bike lanes, I must honestly tell you that. I didn’t poll 700 people, but I did poll people on Clarendon Road and Avenue D.”

Daley’s comments, which stressed that the handful of people he spoke to was the voice of the community, could usually be dismissed as the normal community board kvetching. But Bichotte Hermelyn echoed Daley’s views and went further, demanding that the DOT abandon its efforts to make the roadways safer in her district.

“Bike lanes work in many different neighborhoods,” she said. “But in this particular neighborhood, I know for a fact — I eat, breathe and live here — and they just don’t want it, you know for many reasons. If you asked me if Community Board 17 wanted the bike lanes I would say no, they would not want the bike lanes. If you ask me, how about Community Board 2? I would say for sure. They want bike lanes.”

Bichotte Hermelyn wasn’t throwing around board numbers on flash cards, but on race cards: CB17 is 85 percent Black, while CB2, which covers Brooklyn Heights, Downtown Brooklyn and Fort Greene, has a population that’s only 22 percent Black.

As a result, a higher percentage of victims of road violence in Bichotte Hermelyn’s district are people of color. Between 2017 and October of this year, 416 cyclists have been hurt in crashes and three have been killed. Of the surrounding community districts, the only one where more cyclists were injured in the same time period was Community Board 14, which is also a safety priority district where the DOT is trying to build a bike network. CB17 is also tied for the most cyclist fatalities with Community Boards 16 and 18.

Shouldn’t safety come first?

Within six weeks of taking office in 2014, Mayor de Blasio launched his Vision Zero initiative to encourage cycling and keep bike riders safe. Cycling has definitely increased since then, but safety improvements have been limited to mostly White, mostly wealthy neighborhoods. And the result has been tragic in Community Board 17: in 2014, de Blasio’s first year, there were 3,135 reported crashes, injuring 57 cyclists, 248 pedestrians and 1,019 motorists. In 2019, the last full year not affected by pandemic driving patterns, the number of crashes increased 16 percent to 3,643, and the number of injuries to cyclists increased nearly 60 percent, to 90 injuries. Last year, 107 cyclists were injured.

And the carnage isn’t limited to just crashes involving bike riders. Overall, there have been 15,596 crashes that injured 6,836 people in CB17 since the start of 2017, an astounding nine crashes per day in the district. A large percentage of those injured people are people of color.

That’s why cyclists in East Flatbush are pushing back on Bichotte Hermelyn’s suggestion that Black people don’t ride bikes — because Black people are the ones whose red blood is so often flowing in the streets.

“I don’t know why they think people don’t bike in that community, there’s actually a lot of bikers there,” said Tyrelle Taylor, the chief marketing officer at MBR Cycling, a Black-led bike club in Brooklyn. “As someone who reaches thousands of cyclists in the Brooklyn area, I know a lot of people, especially in predominantly Black neighborhoods, would enjoy having their own bike lane.”

Lou Céspedes, a 30-year resident of the neighborhood and a former candidate for the City Council, said it was absurd to suggest that only “outsiders” or “newcomers” are cycling in East Flatbush.

“If I sit on my stoop during any part of the day, two-thirds of the people that are riding their bike are Black, and one-third are White,” said Céspedes. “You see Black riders, or delivery guys on their bikes all day, and they’re Mexican and Black. It’s just incredible that [Rodneyse] would say such a thing because it’s not based on any kind of reality. … It’s inexplicable to me, other than the fact that she’s trying to reaffirm to her voting base that she’s gonna toe their line.”

In addition, Taylor pushed back on Bichotte Hermelyn’s assertion that cyclists “do not live in the district, they’re going through the district.” Some cyclists do, indeed, bike through the neighborhood — but those cyclists deserve to be safe, too.

“Bikers come all the way from even Canarsie to meet up in East Flatbush to go downtown. I know they would love bike lanes in the neighborhood,” said Taylor.

Heard it all before

Contrary to Bichotte Hermelyn and Darrick’s suggestion that the DOT is uniquely steamrolling East Flatbush, the opposition to the bike lane network is depressingly familiar to any bikelash veteran. Community boards in Sunnyside, Bay Ridge and the Upper East Side have all had members of the public or leadership drag out fights over the totally unique reasons why that particular neighborhood can’t handle a bike lane. Gale Brewer and Adriano Espaillat’s opposition to the Dyckman Street bike lane in 2018 was such a rerun that there were bullet points explaining how their every objection was an echo of recent history.

Leadership in White neighborhoods also is known to attempt the “cyclists aren’t from here” gambit.

“The majority of the people on the bike path in this district on Ocean Parkway are not from this district,” Brooklyn Community Board 15 chair Theresa Scavo said in 2019 when discussing the philosophy of community board control of bike network planning. “They’re coming from the north usually or from the south, but the people that are there are not really from Southern Brooklyn.”

Bichotte Hermelyn’s opposition to bike lanes also contains a pro-driving perspective that is very out of step with her own party’s call for strategies to combat climate change. In 2019 Bichotte Hermelyn was a leader in the effort to oppose congestion pricing, arguing at the time that it would somehow create a situation where some people would be allowed to enter Manhattan for free while others would not.

She changed course once it was clear that the measure would pass. But she has not abandoned her support for car driving. At the recent community board meeting, she said she opposed bike lanes because “people drive in our community.” Yes, residents of Community Board 17 do drive, but vehicle ownership in the district mirror the citywide car-owning minority. In CB17, 55 percent of households don’t have access to a vehicle, according to the Census. Only 25.5 percent of workers in the area commute to work in a car, the vast majority with short commutes. In fact, Census numbers also have shown that roughly 10 percent of residents who don’t commute into the central business of Manhattan do so by bike or on foot.

And those commuters are the most vulnerable. Black and Indigenous people suffer traffic deaths at a higher rate than the population as a whole — and that fact, coupled with a lack of bike lanes, makes it difficult to grow cycling as a mode share, which perpetuates the “people drive” perspective of electeds like Bichotte Hermelyn.

Mayor Adams will change this

The Assembly Member supported Adams’s candidacy for mayor, but on Thursday in Brooklyn, the mayor-elect indirectly addressed opposition to bike lanes that comes from retrograde officials like Bichotte Hermelyn.

“When you try to do infrastructure, bike lanes, in communities of color, you get a lot of pushback, because people are saying, ‘You’re coming in and not talking to us when you’re doing it,'” Adams said, promising to “meet people where they are” but persuade them nonetheless. “You have to meet people where they are … and take them where you want them to be.”

The DOT’s own data shows that even painted bike lanes have helped make streets safer and increase cycling in neighborhoods where paint goes on the ground. A new study from the agency found that painted bike lanes reduced injury risk on a street by 32 percent, and that cycling volumes increased 50 percent after the installation of painted and protected bike lanes.

Despite the lack of any real bike infrastructure in CB17, people still biked in the area enough to rack up enough severe injuries for the city to identify it as a priority bicycle district, one of 10 such areas where the DOT was supposed to install 75 miles of bike lanes by 2022. Asking to delay the project for “additional study” as Bichotte Hermelyn did is the kind of thing that will only cause more carnage in the area.

Black blood is red

Cars do outnumber bikes in CB17. But scores of people are put at risk simply because they don’t use a car to get around: deliveristas on e-bikes, people pulling up to a bodega on their bike to grab a coffee, older New Yorkers on Rad Power Bikes full of tricked out gear, people on e-scooters. One cyclist who stopped to talk at the corner of Brooklyn and Farragut avenues said he regularly rode around the neighborhood even though he lived just outside of CB17 itself, his presence there highlighting the absurdity of Daley’s and Bichotte Hermelyn’s idea of letting “the community” opt out of a citywide safety program.

“Hell no,” said Ricky Morton, who lives on East 21st Street and Ditmas Avenue, when asked if he felt safe on his bike. “You see I’m riding on the sidewalk. Police want to give me tickets to ride on the sidewalk, but I don’t have a choice, because of these cars.”

Other cyclists agreed with Morton’s read of the safety situation.

“There’s cyclists, all throughout this neighborhood, and cyclists moving commuting in and out of the neighborhood,” said Stacey Pettice, a Crown Street resident and staff member with the MBR. ” I’m always thinking about what route can I take or what streets I feel the safest on because because of either how the bike lane is positioned, or there’s no bike lane at all and there may be heavy traffic. So I’m always thinking about about whether this is a safe route for me, especially if I’m riding by myself, where I don’t feel as protected.”

Other political leaders in the area recognize this at least, and said they’re supporting the proposed bike network.

“No neighborhood in New York City is monolithic, including the neighborhoods that comprise CB17,” said incoming City Council Member Rita Joseph, who will represent a piece of Community Board 17 after taking office in January.

Joseph pointed out that when she won the primary this summer, finishing in second was street safety advocate Josué Pierre, evidence, Joseph said, of her neighborhood’s desire to expand the city’s bike lane and street safety effort.

“Broadly speaking, the folks who live in the CD40 portion of CB17 support enhanced street safety measures,” she said. “At the end of the day, the fact remains that climate change represents an existential threat to humankind and transportation is the second largest emitter of greenhouse gases in NYC, trailing only buildings. If we are serious about tackling climate change, our city must make non-automobile transportation, including biking, feasible and safe,” she said.

And given that the DOT has shown up to do virtual workshops and spent the spring and summer of 2021 talking to people in person, it’s clear the city is at least attempting to move slowly to introduce some basic safety measures, the kinds of things that are able to find support among residents.

“I’m a homeowner in the area and I’m part of the County Committee, and I know that a lot of people bike in this area,” said Claudia Galicia, a longtime homeowner who lives on Martense Street.

Galicia was herself a victim of both traffic violence and police ignorance of the law when she was doored in 2019 as she biked on Flatbush Avenue to get home. The incident has stayed with her since it happened, she said, even as she still relies on her bike to get in and out of a neighborhood where she’s seen more vehicle traffic using the local roads instead of a slimmed-down Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

“Really, my bike is the transportation that I use to get to things, but with the heavy traffic now that’s coming from the highway, it’s going to be more dangerous. I have a child with special needs, and I have a bike trailer. But since the accident I don’t use it anymore. If there are no bike lanes where I can bring my kid then, I can’t put her on right now.”

The DOT confirmed that it was still committed to the project — and Mayor de Blasio said Bichotte Hermelyn was practicing a classic form of “pure rejectionism.”

“We certainly saw some of that around Queens Boulevard, which didn’t make sense to me because fixing Queens boulevard what had been called ‘The Boulevard of Death’ saving lives was mission critical. And we had the conversation and respectfully said, ‘Sorry, we have to do this for the safety of all New Yorkers. There’s a right way to have the conversation and a right way to listen, but in the end, we make the decisions based on safety and the principles of Vision Zero.”

A spokesperson for Bichotte Hermelyn gave a familiar statement on the situation, explaining that the Assembly member is not opposed to bike lanes in general, she just opposes these bike lanes.

“[She] supports bike lanes and green transportation alternatives, and … making streets safer is a top priority for her,” said spokesperson Sabrina Rezzy. “She is alarmed by the rising rate of pedestrian and cyclist fatalities. In this instance, residents of the community spoke up against the placement of this proposed lane.”

Rezzy declined to provide a list of alternative locations that Bichotte Hermelyn supports for the bike lanes.

— with Gersh Kuntzman