Safety Third! DOT Proposes Unsafe Bike Lanes in a ‘Priority’ District In Brooklyn

Who wants to settle for the bronze standard?

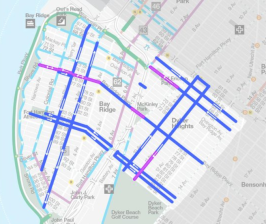

The Department of Transportation set aside requests for secure, protected bike lanes from a Brooklyn community board and will instead create a bike network for parts of Flatbush, Midwood and Kensington that is comprised entirely of painted lanes and sharrows — treatments that the agency has long admitted are substandard (and often end up as double-parking lanes anyway).

DOT Bike Program Director Hayes Lord showed Community Board 14 a proposed “bike network” that the agency hopes will bolster the neighborhood’s existing painted lanes with … more paint.

Some of the bike lanes, located on Dorchester Road and East 14th, East 15th, East 17th and East 18th streets, would be true painted lanes (aka Class 2 bike lanes). On some other two-way streets — like on Foster Avenue, Farragut Road and on busy Cortelyou Road and Avenue M — the agency is offering a painted lane on one side and a shared lane (with sharrows, aka the “chevrons of death”) going the opposite way.

Other two-way streets would be painted with nothing but sharrows.

What’s with all the paint? Lord explained that the agency that long has said it operates by the rule “Safety first” actually does not.

“We honestly didn’t look at protected bike lanes because we wanted to at least start establishing the network to fill the current need and then be able to go back to the community,” said Lord. “As many of the cyclists know, we upgrade our bike facilities when we can. So, you know, this provides the opportunity to lay the groundwork, and then the next iteration could be protected.”

Lord explained the real reason behind the reliance on paint: the agency was not interested in removing any parking. One meeting attendee blasted this aversion to even broaching the subject of taking away parking, the same kind of attitude that led the DOT to only institute painted lanes in Bay Ridge two years ago.

“We have to remove the constraint that we can’t take away any parking spaces, which just feel so strange because bike lanes would serve so many more people than the one parking space, which can only really serve one person’s car,” said meeting attendee Elizabeth Denys, adding that they had started riding their bike during the pandemic and found it safer to bike around in other people’s neighborhoods rather than their own.

Another resident expressed frustration with the decision to start with paint on the hope that the agency will someday return with something safer. Wait ’til next year may have been a Brooklyn Dodger fans’ lament, but it’s not an appropriate response to people who want to get around safely on a clean form of transportation, said John Pouliot.

“The answer is actually to go way further in the direction of taking away parking and protecting people,” he said. “But we don’t want to admit that … parking seems to be this protected class. So I would love DOT to actually stop giving presentations with sharrows that make me feel like I’m going to die because of somebody beeping behind me, and start doing presentations that remove a little bit of parking, especially on Cortelyou with so many delivery cyclists and businesses and people walking everywhere. What a ripe place to have a protected bike lane, two ways even, where people can actually use a street, instead of just leaving their car there all night, which I personally see all the time.”

The frustration is understandable especially given that Community Board 14 is one of the DOT’s 10 Priority Bicycle Districts, which are areas that the DOT determined had both a high share of cycling deaths and serious injuries and a lack of bike infrastructure. CB14 has been the site of significant traffic violence. From 2017 to 2019, which Streetsblog uses as measuring stick for its pre-pandemic traffic environment, there were 12,158 total crashes, which is roughly 11 crashes per day in a relatively small part of Brooklyn. Of those crashes, 2,297 collisions injured 328 cyclists, 751 pedestrians and 1,985 motorists, killing one cyclist and seven pedestrians.

CB14 is also a community board that mirrors the city’s larger car ownership trends, per the Department of City Planning. Fifty-four percent of households do not have a vehicle, and 35 percent of households have one vehicle. Sixty percent of residents commute to work with public transportation, and 20 percent of residents drive to work alone.

The community board did not take any vote on the proposed paint network, and Lord said that no work would be done on the street until April, 2022 at the very earliest, which means that nothing about Wednesday’s presentation is locked in. But bike advocates questioned the tactic of starting from a place of weakness, especially when painted bike lanes don’t automatically get turned into full protected lanes.

“Why would you have two bruising battles instead of just getting it over with?” asked Bike New York Director of Communication and Advocacy Jon Orcutt.

Orcutt, a former DOT director of policy, said that he didn’t think it was a standard practice for the agency to return and add barriers of any kind to painted bike lanes, except on rare occasions. Comparing the DOT’s bike maps from 2015 to 2021 shows that there have been a few instances where a blue line indicating a Class 2 lane on a map becomes a green one indicating a Class 1 lane. However, the reason for those upgrades is usually a grim story, namely a high profile death.

Central Park West, Skillman and 43rd avenues in Queens, and Ninth Street and Grand Street in Brooklyn all made the blue-to-green upgrade between 2015 and 2021 — but each of those roadways was a site of a crash that killed one or more vulnerable road users.

DOT Commissioner Hank Gutman said that the feedback from the public could possibly result in an upgrade to the plan before the paint dries, as it were.

“We show up at those meetings to listen to the input of the communities and we go back and reassess what we’re doing,” Gutman said on Thursday. “I can promise you the team has gone back, they’re taking that into account, they’re figuring out why, and figuring out if there’s a way to improve it.”