EXCLUSIVE: City Cleanup Corps to Take Over Running Fort Greene Open Streets — Others to Follow?

It’s a new day for open streets.

Starting today, the City Cleanup Corps will replace volunteers in setting up open streets barricades on two key Fort Greene streets — evidence that the city is finally answering advocates’ demands that the Department of Transportation take over the massive volunteer effort required to keep the city’s few dozen open streets free of cars from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. daily. The CCC effort in Fort Greene will soon expand to include moving the barricades off the street as well.

“It’s terrific,” said Phillip Kellogg, who has been part of the large volunteer effort along Willoughby Avenue, South Portland Avenue and Hall Place — three extremely popular open streets primarily because of the work of the volunteers to keep cars off the roadway. “The public space at DOT was always supportive, but now it is putting real resources into it. The fact that the city is taking over its own program and make it real is extraordinary.”

Kellogg is hoping that, eventually, the open streets program in his neighborhood can be 24-7 — a demand made by other communities where the car-free streets are hugely popular, such as along 34th Avenue in Jackson Heights, also known as the city’s “gold standard” open street.

“Getting the Cleanup Corps to operate the barricades is something we have been pressuring DOT for for many months,” said Jim Burke, who oversees an even larger volunteer effort in Jackson Heights. “We met with the CCC and were told that we would have someone to open and close our streets, but no details or timeline were given. It sounds great.”

The City Cleanup Corps has been setting out barricades along Avenue B on the Lower East Side, but volunteers there say they still need to remove the barricades at night, and do both jobs two days a week, when the CCC workers are not available. For the most part, the CCC has been cleaning along many open streets, answering a major complaint of a small number of open street opponents who point out that the popularity of the program has led to a rise in street trash.

But the Fort Greene CCC effort — which will include South Portland Avenue between DeKalb Avenue and Fulton Street, and Willoughby Avenue between Fort Greene Park and Hall Place — is the first seven-day-a-week effort and is expected to be the first to grow into a full “open, close and maintain” program. It’s the culmination of more than a year and a half of activist effort, which began last May, when the initial, small open streets program was run by police before being turned over to volunteer groups, which led to successful open street programs only in areas where large groups of volunteers could be organized. Despite a city promise from the very start to help struggling neighborhoods, the open streets program was strongest in wealthier communities.

Kellogg said it is “very big for this community because volunteer burnout is real. It’s not sustainable.”

“We are eager for a permanent solutions,” he added, echoing so many other neighborhoods where organizing scores of volunteers has proven a challenge. “Barricades are not the answer. They need to be replaced with something effective that doesn’t drive people, including car drivers, crazy. These challenges are universal. We cannot wait until spring.”

It is likely that Kellogg and his neighbors will, indeed, have to wait. The Department of Transportion was supposed to reveal in June a permanent design solution for the open street on 34th Avenue between 69th Street and Junction Boulevard, but the agency punted that decision off until fall at the earliest, as Streetsblog reported.

A small band of pro-car opponents is demanding that the existing open street be truncated or have its hours reduced. Drivers have also complained that the barricades are too difficult for them to maneuver past — but, as Fort Greene discovered, that’s entirely the point.

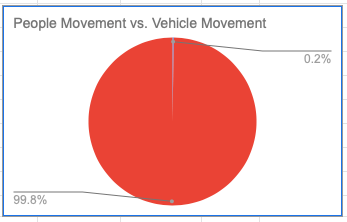

Data compiled by the open street volunteer coalition in Fort Greene (and given exclusively to Streetsblog) showed that non-car users of the roadway outnumber car drivers 99 to 1 (there are some cars, of course, because open streets are only off limits for thru-traffic, to allow for locals to access their homes or garages).

“Our data shows that the key to a successful, widely used, open street is to prevent thru car traffic by making it difficult to enter the street in a car,” said Mike Lydon, a neighborhood resident and principal at Street Plans, an urban design firm. “If car drivers start creeping in, walkers don’t feel comfortable and the numbers drop. As difficult as it has been for volunteers to block off the street, we’ve shown how successful an open street can be if it truly reduces the amount of traffic down to only people who must get to a particularly building, which is a very small number.

“However the barricades morph in the future, our numbers show that they cannot become so permissive to drivers that the open street is no longer viewed to be safe,” he added. “If we reach that threshold of cars, the program loses its effectiveness.”

Lydon’s numbers are especially clear for Willoughby Avenue, where there are often three barricades per intersection to really keep out cars. On two typical days in June, volunteers counted 768 cyclists, 3,352 pedestrians, 431 joggers, 318 people using assisted devices, 515 dogs being walked … and just 12 cars.

“This is why our open street is so great,” said Lydon. “The fewer cars, the more people use it.”

Meanwhile, on South Portland Avenue, the barricades are set up to allow drivers to easily, albeit slowly, access the street. As a result, the street is not as popular with pedestrians.

“There is a higher numbers of vehicles,” Lydon said. “So we or you can see that if the DOT tries a chicane, you can expect more vehicle use. It’s still low, but it’s more than if you put real barricades.

Other open streets groups feel the same way about keeping cars out, which is why the use of CCC workers is so crucial.

“It’s exciting that what started as citizen activism is being institutionalized,” said Sophie Maerowitz, who oversees the volunteer effort on Avenue B, where some opponents have been aggressive towards open street volunteers. “Having uniformed, regular staff will reduce harassment of volunteers on the street, which had been on the rise again with warmer weather and hotter tempers. Volunteer organizers have been praying for this moment for months.”

Maerowitz added that the volunteer effort in most neighborhoods will truly become unsustainable in September, when many workers will return to offices, making it extremely difficult to sign up volunteers to put out barricades at 8 a.m. and remove them at 8 p.m.

The DOT confirmed the CCC involvement in Fort Greene, but declined to answer any questions about other neighborhoods, including Jackson Heights, North Brooklyn and the Lower East Side, which will certainly also demand CCC support to replace the hundreds of volunteers that is difficult to organize and deploy through all seasons, individual member crises, vacations, holidays, etc.

Agency spokesman Brian Zumhagen did say that the CCC is only funded through the end of this calendar year, but the use of city-paid workers through the end of the year “will provide us a foundation for public space stewardship moving forward.” Nonetheless, that still means it will be up to the next mayor to keep this program going, or create another similar program, or devise a different solution to keeping open streets going.

During the campaign, presumptive mayor Eric Adams expressed substantial support for the overall open streets idea, and also signed the petition calling for a permanent, 24-7 linear park on the Jackson Heights open street.

Adams’s support makes sense, giving how popular the open streets program remains with New Yorkers of all races and income levels. In a survey commissioned by Streetsblog earlier this year from the respected polling firm Data for Progress, we learned the following:

- 67 percent of voters said the city was right to close some roadways to traffic to create space for restaurants and people. The support was strong across the board:

- 66 percent of voters making less than $50,000 and 67 percent of voters making more than $150,000 agreed.

- 64 percent of Latino voters agreed (versus only 23 percent who didn’t)

- The support was also strong in all age groups.

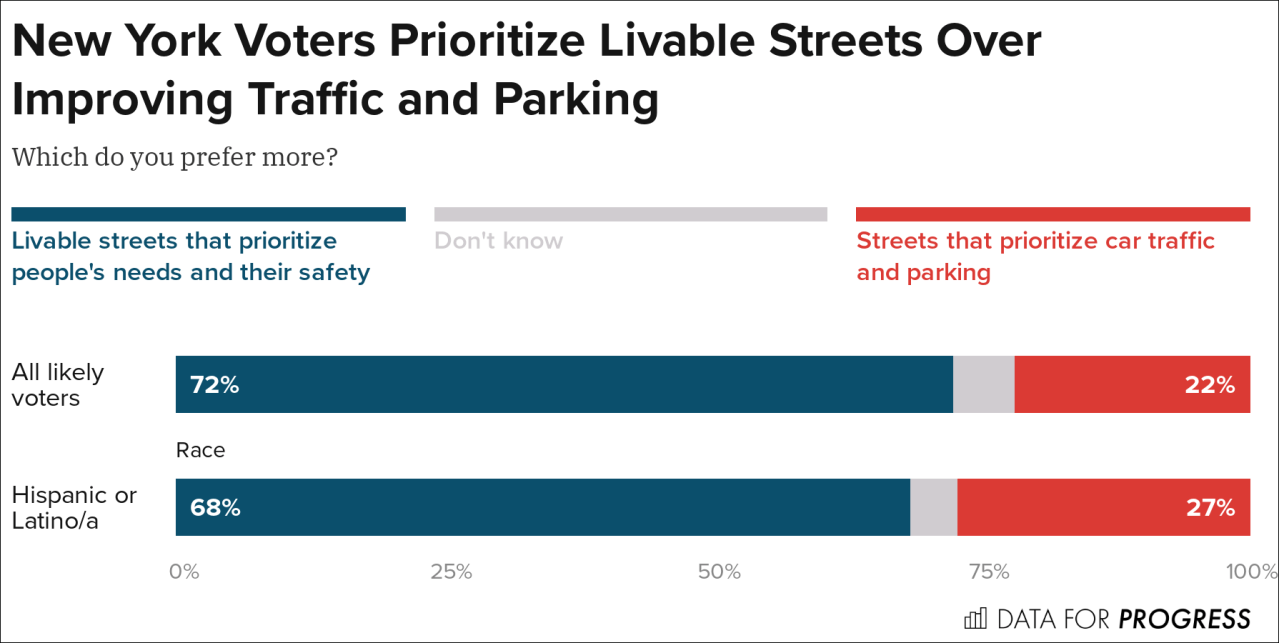

- 72 percent of voters say they prefer “livable streets that prioritize people’s needs and their safety.”

- The number rose to 77 percent among Black or African-American voters.

- And 72 percent of voters support livable streets in all income levels.

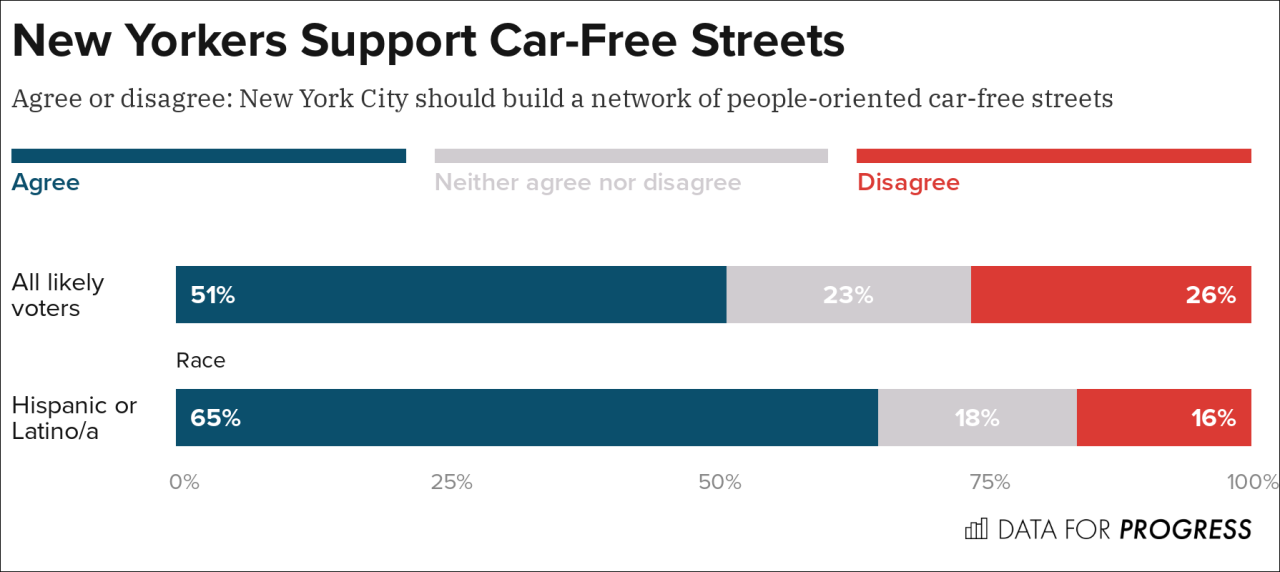

What is even more interesting is the racial breakdown of that survey. The overwhelming majority of voters who identified themselves as Latino or Hispanic support open streets (and, indeed, a majority — nearly 58 percent — of the people who live in Census blocks that straddle 34th Avenue identify as Hispanic or Latino). No matter how Streetsblog asked the question, we received largely the same answer from these voters, as the charts below show: