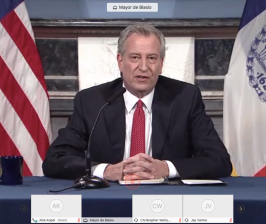

OPINION: De Blasio Must Challenge Status Quo to Make Open Streets Great

Mayor de Blasio doesn’t have my number on speed dial, but he can call me anytime to ask for advice about making his Open Streets program permanent.

As an urban planner, college professor and open space advocate, I’ve spent my career thinking about how American cities can be more sustainable, livable and equitable. I’m also fortunate to live in Jackson Heights, home to the 34th Avenue Open Street, a 1.25-mile corridor where I walk, jog or bike almost every day, and which my kids use as a much-needed addition to the neighborhood’s small park.

So, when the mayor calls, I’ll give him the following advice:

Never let a crisis go to waste.

COVID-19 has created opportunities for unprecedented responses like expanded outdoor dining and Open Streets. But, as the crisis recedes, we have to remain steadfast. We can’t give up just because it is politically or procedurally difficult to make successful emergency measures permanent.

Remember that the status quo is not divinely inspired. We made these choices, and we can make new ones.

By the DOT’s own estimate, roadways comprise 27 percent of the city’s land area. Mayors have always built new roads to achieve political or economic development goals. But no one ever said a mayor couldn’t also remove them when those rationales no longer make sense.

SIDEBAR: HERE’S WHAT THE TRANS ALT-LED OPEN STREETS COALITION IS TELLING HIZZONER

Focus on people, not cars.

Today, even the best Open Streets (like 34th Avenue) feel like places for cars. Pedestrians feel like intruders. We can invert that dynamic. Luckily other cities — Bogota, Barcelona, Paris, Oslo, Copenhagen, Amsterdam to name a few — have already developed approaches we can adopt. And it’s worth remembering that these places were once car obsessed. They found ways to break that obsession, and so can we.

Many city officials say 'but we are not #Amsterdam!'

Well, neither was Amsterdam. Human-centric streets are a CHOICE that takes political will and perseverance. It is something ANY city can do!

~1e Van der Helststraat, 1978-2015 pic.twitter.com/lnWHfVdnMo

— Cycling Professor ? ? (@fietsprofessor) March 15, 2021

Reach out for help.

The DOT is ultimately an engineering agency whose mission is “the movement of people and goods.” The goal of Open Streets is to enhance livability. This is not the DOT’s mission. In addition to its very capable engineers, we need input from visionary urban planners, architects, landscape architects, public artists, and others. Agencies like NYC Parks, the Department of Design and Construction, and non-governmental experts should have a central role in creating a world-class Open Streets program.

SIDEBAR: DE BLASIO SHOULD MAKE 34TH AVENUE A COVID MEMORIAL

Encourage generosity.

Driving is an inherently self-centered behavior, and I speak as a car owner. No aspect of driving encourages selflessness, especially not the amount of space it requires. The city has more than 6,000 linear miles of streets and fewer than half of city households own a car. Removing traffic from a few miles of streets scattered around the city is an incredibly generous act, and refusing to do so is selfish. We are better than that.

Embrace system-wide solutions. Don’t fixate on narrow problems.

Removing traffic from Open Streets presents some challenges, but we can embrace these as opportunities. Ambulances, garbage trucks and delivery trucks will be affected. But this provides an opportunity for creative problem-solving. Indeed, delivery drivers in Jackson Heights have found the 34th Avenue Open Street has made their job easier, not harder. Sometimes innovative solutions to one challenge can help address others.

Don’t confuse temporary tactics with long-term strategies.

Open Streets was created quickly in a time of crisis, but the success of 34th Avenue and other ad hoc measures highlights the power of ambitious experimentation. Now comes the hard work of integrating Open Streets into city operations. Relying on residents to move barricades and fundraise for amenities is not fair to one group of taxpayers who deserve government services just as much as drivers. Nor is it fair to residents in neighborhoods that lack access to the political and financial resources needed to augment the city’s minimal efforts.

Change is hard, but people do adapt.

I spent a decade helping remove cars from one block of roadway in Jackson Heights. We received hate mail from neighbors and were called naïve by some elected officials. Today that former street is a much-loved component of our neighborhood park and many of those elected officials can be seen smiling in ribbon-cutting photos. Imagining streets as places to do anything other than move and store cars is hard for many people, but once they experience other realities, their opposition tends to vanish.

As the city emerges into a new post-COVID reality, we must embrace the fact that the world is going to be different. The ongoing climate and racial justice crises only compound the need for rapid, visionary change. Cities will adapt, and solutions that address the greater good may be hard for some people to accept in the short term. But now is not the time for anemic half-steps. The way we use public space must evolve to embrace our new realities.

New York should lead this evolution, requiring both bottom-up pressure from residents and top-down leadership from the mayor and others in government. Bureaucracies are by nature ponderous, plodding and risk-averse. That’s not an insult, it’s just reality. We must demand innovative solutions and support elected officials who prioritize those demands. We will have to push the mayor and his administration well beyond its comfort zone. Accepting less is giving up before the battle even starts.

Donovan Finn is assistant professor of Environmental Design, Policy, & Planning at Stony Brook University and a founding member of the Jackson Heights Green Alliance. He’s on twitter @donovanfinn and Instagram @covidstreetscapes