OPINION: Mayor de Blasio Leaves Street Vendors Out in the Cold

Stores get sidewalk space as a vendor-relief bill languishes. Let's stop discriminating against these vital small businesses.

As the coronavirus pandemic surges anew, City Hall is providing some much-needed relief for small businesses in the form of “Open Storefronts” — a program, similar to “Open Restaurants,” that lets brick-and-mortar retail stores use the sidewalks in front of their businesses for sales. That effort is laudable, and it should help stores to recoup months of revenue lost during the pandemic.

Yet the new program highlights the hypocrisy and discrimination of the city’s approach to business licensing. Even as the city moved quickly to establish Open Storefronts and Open Restaurants, it has left thousands of street vendors literally out in the cold.

There is a remedy. The city immediately must pass Intro 1116 — a bill that would provide relief for struggling street vendors, which has languished in the City Council, despite 29 co-sponsors.

Yet even if Intro 1116 passes, the city must address a glaring injustice: the different way that it treats street vendors and brick-and-mortar businesses, which amounts to an unfair double-standard.

The recent history is clear.

Let's take a look at the regulations side by side. Left is #OpenStorefronts expansion. Right is #streetvendor regulation.

If vendors are even 1" out, they face fines, harassment, even arrest@NYCMayor & @NYCCouncil must do better to end this tale of two cities #Intro1116 pic.twitter.com/YNWdNSwMss

— Street Vendor Project (@VendorPower) October 29, 2020

Mayor de Blasio acted with alacrity to “cut the red tape” for Open Restaurants and Open Storefronts, changing sidewalk rules almost overnight and setting up relatively simple enforcement and siting requirements. There are no caps on the number of establishments that can apply for permits: 40,000 retailers are expected to sign up for “Open Storefronts” by filling out an online form; more than 10,000 restaurants have used “Open Restaurants” during the past few months.

By comparison, street vendors must follow Byzantine rules and regulations that restrict them from hundreds of streets. In Intro 1116, they are asking for a paltry 400 mobile food-vendor permits a year for 10 years and the establishment of a civilian agency for vendor compliance. It’s not an impossible lift.

Street vendors have been waiting almost 40 years for relief from the city’s outdated vending system — which places arbitrary caps on the number of vending licenses and permits and leaves vendors subject to excessive enforcement such as high fines, property seizure, and harassment and arrest at the hands of the police.

Such harassment is hurting real New Yorkers now — and happened as recently as last week in Brighton Beach.

How would you feel if NYPD pulled up on you, handed you a ticket for up to $1,000 & said see you in court —

4 months after @NYCMayor said #NYPD would no longer enforce street vending?@NYCCouncil must take action on real reform for our smallest biz. Pass #intro1116 pic.twitter.com/0nUCy2MvkM— Street Vendor Project (@VendorPower) October 22, 2020

A family was vending clothing from the sidewalk when three NYPD officers pulled up, asking to see their license. They have a certification that authorizes them to sell in stores, but couldn’t afford rent and weren’t able to negotiate the arduous process for a street-vending license.

Last week, the family was fined up to $1,000, during the middle of an economic crisis — four months after the mayor declared that the NYPD would no longer be involved in vending enforcement.

Yet when proposals for vending reform come before the city, the opposition is out in full force claiming that street vendors make “sidewalks impassable” and that the city must add enforcement and siting requirements for vendors before issuing any new permits. Even during the pandemic, the NYC Business Improvement Districts Association, which advocated for “Open Storefronts,” has sought to stifle economic opportunity for vendors by heightening enforcement.

Most street vendors are immigrant entrepreneurs who work long hours in order to support their families even amid a global pandemic and economic instability. They come from the communities most affected by COVID-19. Vendors are the lifeblood of our city, feeding millions of New Yorkers across the five boroughs, from the halal food truck to the ice-cream truck that drives through our neighborhoods during the summer.

When will the city treat street vendors, who have been operating safely on our streets for hundreds of years, as legitimate small businesses? It seems that, during a pandemic, the power imbalance is even more visible as the well-connected obtain relief while the most marginalized communities and smallest businesses continue to face exclusion.

Unless the city explicitly includes street vendors in its plans, the unequal history of enforcement of our public streets will continue, and vendors, who come from communities that have suffered disproportionately during the pandemic, will remain excluded from recovery efforts. New York City must do better to end this “Tale of Two Cities.”

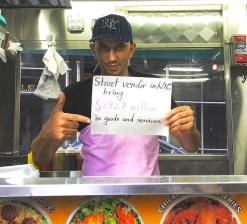

The Street Vendor Project (@vendorpower), a membership-based organization that is part of the Urban Justice Center, works to defend the rights and improve the working conditions of the 20,000 people who sell food and merchandise on city streets.