White Privilege on the Upper West Side: Board Condemns Police Brutality — Then Calls for More Cops!

This is what white privilege looks like.

A community board in the predominantly white Upper West Side spent almost an hour showing support for the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of yet another police killing of a black man, then passed a resolution calling for more enforcement in Central Park by the NYPD — a move that completely ignores the issue that is at the heart of the anti-brutality movement: that cops are far more likely to use excessive force against people of color.

“Especially at this moment, we should not be asking for a law enforcement crackdown in a park,” said board member Ken Coughlin. “The resolution calls for mechanically applying rules and penalties that are designed for city streets, not a place of recreation. Such an approach hasn’t worked in the past and inviting it now is a particularly bad idea. We need solutions in Central Park to keep everyone safe that are appropriate to the unique conditions there.”

The meeting of Tuesday, June 2 started out with a lengthy discussion of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis that featured a discussion of police brutality by the NYPD across the city (though not, more than one person claimed, in the neighborhood’s 2oth and 24th Precincts, of course!). The board passed a resolution by a 47-0 vote supporting full prosecution of the officers involved in Floyd’s murder.

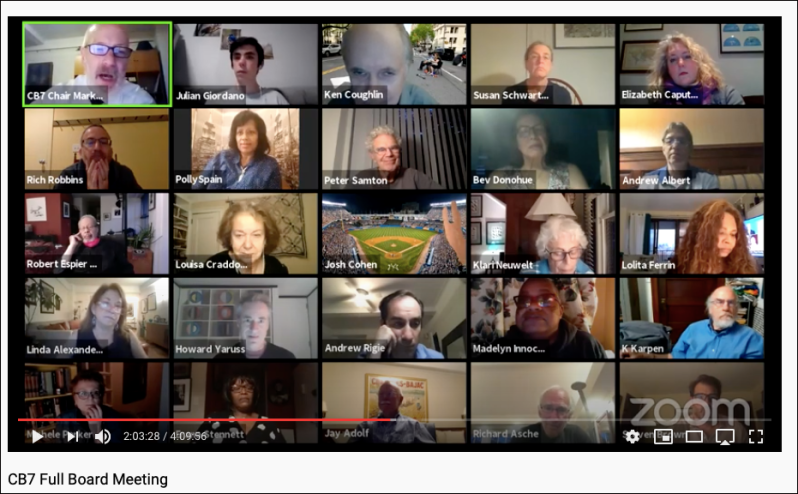

Then the Board turned its discussion to a proposal to call for more enforcement of bicyclists — many of them people of color who would be disproportionately affected by said enforcement — in Central Park. [Watch the full meeting here. The discussion on park enforcement begins at around 2:05.]

For context, the meeting did come at a moment of tension: A few hours earlier, a pedestrian had been hit and seriously injured by a cyclist in the park, as Streetsblog reported. And Central Park is being used — perhaps more than ever, thanks to the COVID-19 crisis — for intense amounts of passive and active recreation. Its roadways — which are still striped, and regulated by lights for, automobiles, even though they have been banished from the park for two years — retain a constant potential for conflict between cyclists and pedestrians. Crashes are rare, of course, but many pedestrians have a perception of danger inside what should be a safe space. Meanwhile, people on bikes complain that they are not given space for their socially responsible form of transportation.

So here is the joint Parks and Environment Committee and Transportation Committee resolution that was before the board:

-

-

-

During the Covid crisis, use of Central Park by pedestrians is an essential means of recreation, exercise, and respite from the need to isolate at home.

-

Cyclists and other vehicles in Central Park sometimes fail to obey traffic laws and regulations such as failing to stop at red lights, failing to yield, and failing to observe the legal speed limit, and there are also cyclists who ride on pedestrian-only paths. This conduct places pedestrians at risk.

-

-

THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED THAT Community Board 7/Manhattan calls on the NYPD and the Parks Enforcement Patrol to increase enforcement of violations by cyclists and other vehicles of traffic laws and regulations and Parks rules to promote pedestrian safety.

Both Transportation Committee chairs — Meg Schmitt and Howard Yaruss — both voted no on the resolution before it came before the board. That fact was pointed out when the resolution was presented by Parks committee co-chairwoman Klari Neuwelt.

“It’s not meant to be controversial,” added board member Barbara Adler. “It just asks for additional enforcement.”

Earth to the Upper West Side: That’s what’s controversial! As several member of the public later reminded: all police forces, but the NYPD in particular, have a well-documented practice of enforcing laws in a way that is racially disproportionate. It was true of stop-and-frisk. It is true of how cops use deadly force. It is true for COVID-19 social distancing enforcement. It’s even true of illegal pedestrian crossing (sometimes called “jaywalking”).

“The last thing we need now is racist over-policing,” said Upper West Sider Andy Rosenthal.

What is needed — as activists have long pointed out — is design of our streets that does not require enforcement by inherently biased cops. Indeed, even a woman who lost her husband in Central Park in a crash with a cyclist has been defiant in her opposition to resolutions like the one that passed this week.

“Since I lost my husband to a cyclist/runner crash on August 3, 2014, I have given a lot of thought to making Central Park safer for pedestrians — and cyclists,” said Hindy Schachter, a member of Families for Safe Streets. “The roadways needed extensive redesign work in 2014 when it was already difficult to realize which spaces were pedestrian only. Now with cars officially banned from the east and west drives, the space cries out for a design that acknowledges and builds on a car free reality. Such design has not come. At some point, advocates brokered by Transportation Alternatives and Families for Safe Streets need to sit down with the Central Park Conservancy, the Parks Department and the police and City Council to discuss long-term changes that make sense for a car-free park.”

The specific issues in the park do need to be addressed. As Streetsblog has long reported, there is no simple way for cyclists to get across the park, because the Parks and Transportation departments, in conjunction with the Central Park Conservancy, have offered no solution — even after cyclist Daniel Cammerman was killed by a driver on one of the park’s transverses last year.

In addition, the roadways inside Central Park are still configured for high-speed travel, with traffic lights that were installed and timed for cars, even though they are banned.

“You can’t talk about ‘enforcement’ until you agree on what you’re enforcing,” one Upper West Sider said after the meeting. “And Central Park is a long way from establishing allocation of space to competing usage, providing appropriate signage and lanes, re-examining the flow and control of traffic via signals that were designed for automobiles. . . and more. Once all that is in place, you can talk about how to enforce it.”

The resolution calling for more police flies in the face of national trends seeking to rein in the police. The school district in Minneapolis, for example, responded to the police killing of Floyd in a different way than CB7 in Manhattan: It ended its contract with the local police department, citing a lack of trust in its ability to equitably enforce the law.

“There is no shortage of ironies,” Yaruss told Streetsblog after the meeting. “The resolution should pose problems for people who worry about over policing as well as for people who worry about under policing. We have looting going on and they want police resources used to monitor bicycle riding in a park.”

Lisa Orman of Streetopia UWS testified in favor of design changes that would minimize the need for enforcement at all — the same strategy that is behind speed bumps on residential streets, road diets and other efforts that force drivers to move slower through public space.

“We need a complete redesign of the Central Park’s drives that reflect the current uses of the park — recreational users, NOT cars,” she said. “There are currently 47 traffic lights, a relic from a time when cars owned the park roadways. Parks and The Central Park Conservancy need to engage with park users and welcome all active forms of transportation and recreation.”

Orman disagreed with CB7 members who “were so upset that bicyclists ‘aren’t where they are supposed to be,'” yet offered little else beyond calling in the cops.

“What cyclists have been saying all along is that we need to feel like we belong and are encouraged to be there, through signage, dedicated paths, fewer traffic lights, and more engagement/education,” she said. “We would also like to point out that all cyclists are also pedestrians; CB7 needs to stop pitting these two vulnerable user groups against one another and, instead, work with all park users on a design that works.”

So, fix the park, yes — but do it without cops.

Gersh Kuntzman is editor of Streetsblog. He writes the Cycle of Rage column, which is archived here.