Op-Ed: Protests Lay Bare Structural Racism in Mass-Transit Policing

Even after COVID-19, the governor and MTA doubled down on hiring more cops for the subway. Will a popular movement open a debate about the control of public space?

As New Yorkers juggle hand sanitizer and dodge errant tear gas canisters, they may find it hard to recall that, only six months ago, Gov. Cuomo and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority were clashing with activists and legislators on the issue of fare evasion.

How innocent we were! At the heart of the clash was Cuomo’s plan to hire 500 new MTA officers as a way to deter “theft of service.”

Theft of service? Looking back on that pre-COVID-19 moment illuminates much about our present situation.

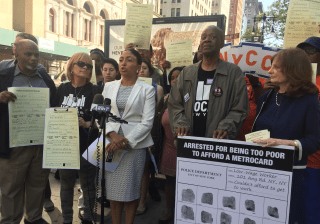

For activists, of course, the problems with Cuomo’s plan were immediately obvious. The plan stoked ongoing concerns around racial profiling, and seemed to imply that the MTA’s mounting problems were really the fault of the city’s poor.

Another key problem was simply math. As Streetsblog noted, the MTA’s proposal to spend “$249 million on new cops to save $200 million on fare evasion” belied anything approaching sound economic sense. In a letter to Cuomo, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said more or less the same thing: Rather than a hiring spree, “desperately needed resources would be better invested in subway, bus, maintenance and service improvements.”

In the last six months, a great deal has changed. Gone are the Halcyon days in which fare evasion or “theft of service” elicit spirited debate.

Today, the issues facing the MTA and New York City Transit appear more existential. After Cuomo’s March 20 “New York on PAUSE” declaration, daily transit ridership fell by 90 percent. By mid-April ridership on the subway had reached a historic low of 365,000 daily trips — down from 5.56 million trips a year before. Losses in fare revenue have been extensive.

The MTA’s financial situation remains shaky despite the fact that the agency has received federal and state aid and new powers to borrow from its capital budget — and especially given the possibility of another outbreak. Beyond the hit to transit budgets, the human costs also have mounted. As of this week, more than 60 transit workers in the city — most of them bus drivers — have succumbed to COVID-19. Transit in the city is facing a new reality — one that has made a mockery of the old bugaboo of “fare evasion.”

Yet in Albany, our leaders carry on as if nothing has changed. In mid-April, Gothamist reported that, despite $8 billion in COVID related losses, the MTA still plans to plow ahead with its decision to hire 350 new MTA police officers. Having already hired 150 since January, the MTA will expand the force’s ranks by 150 in July and by another 200 in December. MTA spokeswoman Meredith Daniels defended the decision by saying that it simply reflects the MTA’s top priority: “to provide a safe and secure transportation system.”

The takeaway is clear: Despite the radical nature of the change that has befallen the world, and New York City in particular, the MTA remains bewilderingly consistent in its eagerness to expand the policing of mass transit.

Even though Albany may not have changed, New York has. In the teeth of the MTA’s obduracy, a growing share of the public simply won’t stand for it anymore.

These past weeks, amid a wave of global demonstrations in response to the killing of George Floyd, protesters are questioning how we fund the police versus how we fund everything else — from public education and healthcare to public transportation. They illustrate the point simply by juxtaposing images: The first image is usually of a nurse or bus driver wearing a garbage bag fashioned into PPE. The second image is of a police officer armed to the gills with both the new military-grade gadgets and an armored vehicle purchased for $250,000 through a Justice Department grant.

I've been seeing a lot of tweets of people noting how kitted out police are vs care workers & I actually did a quick break down of the cost of gear to kit out an officer vs how much it costs to kit out a care worker in PPE. A thread 1/11 #GeorgeFloydProtests #Covid_19 pic.twitter.com/zNE3fwqlpi

— Markerslinger?plays violin as CyberRome burns? (@markerslinger) June 2, 2020

The images bear directly on questions of structural inequality — of which racism is an essential component.

In a society in which leaders have little political appetite to tackle inequality or to address structural racism, and in a city that has become more unequal with COVID and may become more so, the choice to increase the number of MTA police and thus the policing of people of color — like George Floyd — is perversely sensible. It suggests that our policy makers have not only accepted the reality of structural inequality, but that they see their primary task as simply managing it.

The push for more MTA police — despite transit’s financial woes and the retreat of the issue of fare evasion — clarifies what was already clear to activists six months ago: The purpose of the policing fetish is simply the need to control the mobility of the economically and racially marginalized — a population that will face the brunt of the coming austerity.

We must address these structural questions — and now, with hope, we will.

Kafui Attoh (@AttohKafui) is an associate professor of urban studies at CUNY’s School of Labor and Urban Studies. He is the author of “Rights in Transit: Public Transportation and the Right to the City in California’s East Bay.”