Will NYC Finally Get Garbage Out of Pedestrians’ Way?

It’s the city’s version of the five o’clock shadow.

Every afternoon, vast stretches of New York City sidewalks become de facto garbage dumps as high-rise maintenance workers, brownstone residents and single-family homeowners toss big black bags of trash onto the sidewalk in anticipation of the next morning’s pickup.

Finally, the departments of Sanitation and Transportation say they’ll do something about it. Both agencies are cooperating on a formal “request for expressions of interest” from community, industry and advocacy groups to help the city find “creative solutions for containerized refuse and recycling” that will increase recycling to reduce how much garbage actually gets put on the streets, while also lowering the amount of miles traveled by carbon-spewing waste collection trucks.

The agencies are now going through the 19 submissions, which were due on May 31. But the goals of the RFEI were so vaguely worded that it’s anyone’s guess whether any of the proposals will be sufficiently bold to fix the persistent problem of garbage-strewn sidewalks, one that is getting worse as some longtime business zones such as Lower Manhattan change.

“Where we have conversion of commercial buildings to residential, that’s a shift in the waste that’s coming out of those buildings,” said Bridget Anderson, the Sanitation Department’s deputy commissioner for recycling and sustainability. “That waste wasn’t in the original plan, so we have to consider how we respond to the changing use of the built environment. Loading areas are crucial, which is why DOT is a partner on this RFEI.”

New York City has been struggling with trash ever since the Dutch started making it. By the early 19th century, real estate was at such a premium in the city that planners didn’t bother building back alleys as in other cities, a decision that led to the mounds of trash — 12,000 tons a day, citywide — that we see on today’s sidewalks.

There is, of course, no shortage to solutions to the problem of public trash — forward-thinking, overtly planned communities such as Roosevelt Island, Hudson Yards and Battery Park City all designed nifty ways of hiding trash or moving it along pneumatically — but in the real world, there is a shortage of space.

Or is there?

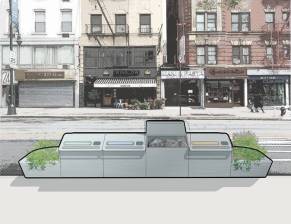

CHEKPEDS, a venerable livable streets advocacy group in Hells Kitchen, submitted a proposal called TOSS, short for Trash Off Sidewalk Space. As the name suggests, the group wants bagged garbage to be put in the street, rather than in pedestrians’ way.

The plan [PDF] would deploy six “Waste Corrals” on a typical side-street block, with each seven-foot-by-20-foot corral holding roughly 85 bags of trash in the same space as one parked car. It’s an attempt to retip the public right-of-way pendulum back towards pedestrians from drivers who want to store their private cars in public space.

“This is simply taking a parking space and putting the bags there instead of on the sidewalk,” said Christine Berthet, a co-founder of the group. “It would do a lot of good for the pedestrians, plus the Sanitation workers won’t have to go through the cars to get the garbage. This is very basic.”

It’s very basic. In fact, it’s exactly how trash is handled the world over. In many modern cities, residents bring their trash to one or several large containers — sealed to keep out rodents — on their block. Americans may scoff at the loss of convenience, but it is common among urbanites elsewhere.

It seems unlikely that the departments of Sanitation and Transportation will take on car owners by fully embracing the CHEKPEDS plan because, Anderson said, New Yorkers wouldn’t likely go for it. In other words, this revolution will not be Sanitized.

“Our intention is not to make residents’ life more difficult at all,” she said. “We want to maintain the convenience factor and if anything, make life more convenient. … We have curbside service. I don’t imagine switching our way of doing business. If individuals [had to] go down the block and drop off the recycling, it might not maximize the amount of recycling. We want recycling and waste to be as convenient as possible. Recycling happens at a much higher rate when it’s convenient.”

Anderson said a likeliest scenario would be collaboration among many buildings on a high-rise block.

“We want building management and building staff to reduce the number of hours they spend on waste,” she added. “And that is about how the building sets up the waste management system, before the waste even gets to the street.”

But under current conditions, the waste never technically even gets to the street. And that’s why most livable streets advocates believe that parking spaces need to be eliminated so that trash ends up in public space that is already being allocated to private storage — currently, mostly automobiles. (The DOT declined to discuss the pilot.)

“Our public right of way deserves better than the status quo,” said Lisa Orman, the co-founder of the Neighborhood Empowerment Project, which works with communities to improve quality of life amid city inaction. “We hope that the city pilots plans that get trash and recycling off our sidewalks, whether that’s in containerized solutions on the street or underground collection sites or something else innovative.”

Anderson said there is hope.

“If a solution would require some parking space, DOT is willing to review it,” she said. “That’s why DOT is involved. We didn’t want to go to DOT after the fact.”

The overall goal of the RFEI is to reduce the amount of garbage — through prevention, recycling and recovery. The city developed a handbook called the Zero Waste Design Guidelines in 2016 to encourage architects and developers to consider how to handle garbage as an essential part of any new designs. Unfortunately, many of the strategies are pie-in-the-sky ideas for buildings that can’t retrofit with massive garbage-storage areas, pneumatic systems or underground garbage bins like they use in Switzerland.

“Developers and architects have not traditionally thought about waste as a component of their design process,” said Anderson. “If waste is an afterthought, it all ends up at the curb.”

The guidelines did point the way to a solution that CHEKPEDS’ Berthet would likely endorse: “Well-designed drop-off collection points on street corners and public plazas could address inadequate storage in individual buildings,”

“Pedestrians don’t have enough space on the sidewalk,” she said. “No one is going to widen the sidewalk. So let’s get the stuff off the sidewalk!”

Chekpeds – Sanitation Rfei by Gersh Kuntzman on Scribd