Five Questions: Should The City Take Over the Transit System?

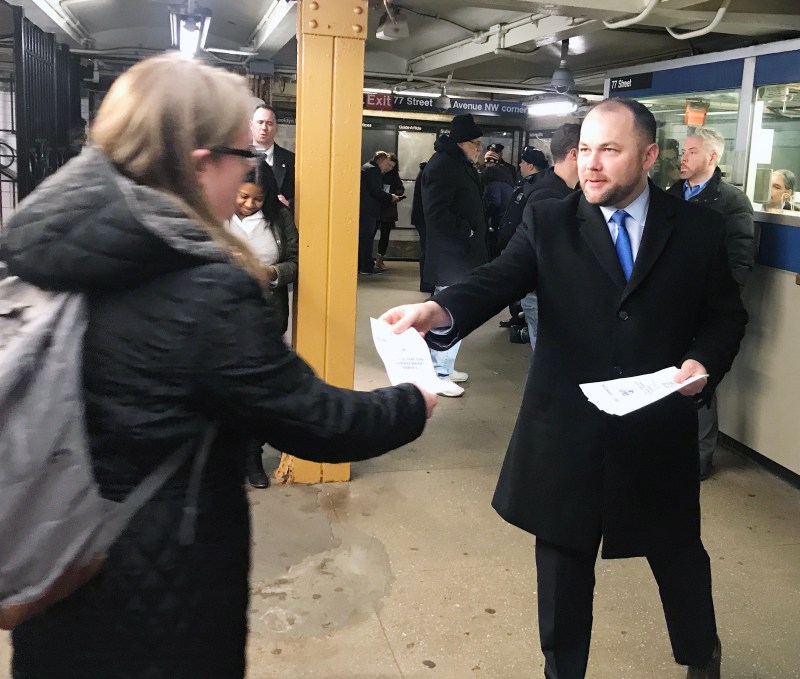

City Council Speaker Corey Johnson will unveil a comprehensive roadmap for a city takeover of its buses and subways on Tuesday.

Wouldn’t it just be better if the city was running its own transit system instead of the governor and his unaccountable MTA?

On Tuesday, Speaker Corey Johnson is expected to unveil a comprehensive roadmap for just that: a city takeover of its buses and subways. After all, city riders, city tolls and city taxes pay for most of the system anyway — and Johnson has already said he isn’t convinced that the governor’s congestion pricing plan would truly put all of the toll money in a lockbox exclusively for New York City’s transit needs.

Johnson is right to be concerned. City residents provide the bulk of the MTA’s revenues, but its expenses hardly reflect that: Nearly two-thirds of the new construction funded by the 2015-2019 capital plan was for suburban commuter railroads, which account for just seven percent of the MTA’s total ridership. And suburban legislators are already angling for that approach to continue.

Still, would withdrawing from the MTA improve the city’s leverage in the never-ending funding debates? We won’t know Johnson’s plan until he unveils it, but we’ve analyzed the basic idea. Could it work? Here’s what you need to know:

What would this even look like?

If Johnson succeeds in his push for city control, a new agency would run the subways and the buses currently constituted as New York City Transit and MTA Bus Company. But any plan is dead in the water unless Johnson’s new agency also gains control of the agency’s fare revenue — and, importantly, the toll revenue from MTA Bridges and Tunnels, which operates entirely within city borders.

Currently, the surplus revenue from bridge and tunnel tolls (after operating and maintenance) is split evenly between NYCT and the MTA — which makes little sense given the breakdown of ridership. That formula is long overdue for a renegotiation, which any city takeover of transit would hopefully hasten. Still, it’s hard to see that happening.

Johnson’s past statements on congestion pricing could hint at what he’s planning to announce on Tuesday. In September, the council speaker suggested that if the state failed to enact congestion pricing, the city could do it on its own. Legal scholars disagree on whether that’s true — but Johnson is one of the few city leaders whose shown any interest in pushing the question.

What’s the case for this?

Let’s phrase that another way: Why the hell not? Given that the current organizational structure has been in place for five decades and counting, and it has led to years of stagnation and decline, Johnson can’t be faulted for wanting to try something new.

By and large, when governments shift control of an agency in one direction or another, operations improve.

“Overhauling the governance structure of a poorly managed place tends to make it better, regardless of which direction the overhaul is in,” said writer Alon Levy, an expert on international best practices for transit system. Of course, Johnson could be using this to give some oomph to his likely mayoral campaign. But a craven political stunt could work in the public’s benefit, Levy argues. If Johnson promises to overhaul the subways and buses, he’ll be far more likely to hire transit leaders to do just that.

“It means that suddenly, you cannot say we have always done things this way,” said Levy.

What would city leadership actually do differently?

Most important: Putting city lawmakers in charge would let every New York City resident know where the buck stops.

At present, the MTA is in the hands of the governor, who more often than not hails from outside New York City. Accountability and oversight, meanwhile, lie primarily with the state legislature, whose members represent the interests of Syracuse, Buffalo, and Rochester as well as the counties of the New York City region.

As a result, questions regarding MTA funding and management are always weighed against the needs or concerns of the rest of the state. So instead of holding hearings on each of the major issues facing the city’s transit system, the state senate’s transportation committee is currently on a region-by-region tour. Despite being the single largest state agency and carrying nearly eight million riders per day, New York City’s transit system is getting the same number of oversight hearings as its counterparts in Long Island, the Hudson Valley, Syracuse, and Buffalo.

“The subways and buses that operate fully within New York City are a New York City local concern,” Second Avenue Sagas blogger Ben Kabak told Streetsblog. “It doesn’t really make sense that the people who are in charge of it and who have the responsibility for it aren’t local politicians.”

Who pays?

Even if the city proved the superiority of its management, however, the state would still control transit funding. The city is unable to levy taxes without state approval. The debate in Albany over who pays and who gets paid would remain mostly intact.

Meanwhile, the city would assume responsibility for New York City Transit and MTA Bus Company’s combined $12-billion operating budget, which represents 13 percent of the $92-billion FY 2020 budget proposed by the de Blasio administration. It would also likely assume responsibility for those agencies’ $40-billion maintenance bill as well as their share of the MTA’s $41-billion debt.

Consider the city’s inability to find the cash to address NYCHA’s $32-billion capital needs — and multiply that by at least two-fold.

“Even if there was a way to basically leave long-term debt behind, the work that needs to be done at transit would require a lot of new borrowing, and that’s going to weigh on the city’s current debt-load,” Citizens Budget Commission infrastructure expert Jamison Dague told Streetsblog. “It’s a huge new expense and capital infrastructure asset that’s going to require a lot of investment.”

Here, Johnson may get creative by finessing some sort of home rule power denied to two centuries of New York City governments, which leads to the most important question…

Is there even a political path?

Many politicians have suggested a city transit takeover over the years. As far as Streetsblog can tell, no one has ever actually ventured to make it happen. Likely for good reason.

Ultimately, any attempt to wrest control of the transit system from the state forces the various counties and jurisdictions to defend their fiefdoms. The suburban counties, for example, actually need the MTA in the hands of the state to keep their railroads running. They don’t have the borrowing power to do it on their own.

Johnson’s forthcoming proposal is expected to including some sort of funding mechanism, which will need the approval of the very same state legislators unwilling to fund NYCT today. It’s hard to see how the city running the subways and buses would make suburbanites less protective of state coffers.

The political path is made even more difficult with Governor Cuomo newly emboldened to take more control over the transit system, and Mayor de Blasio now in his corner. Perhaps stubbornly, the governor seems to want to right the mess he let fester over his first eight years in office.

So why doesn’t Corey Johnson just let him? It’s possible that he does. All politics is performance, anyway.

Perhaps the goal here is simply to expose the interplay between the needs of the city and the rest of the region — and compel elected officials outside of the city to care about the city’s transit system.

And if congestion pricing doesn’t pass in Albany, Johnson’s city takeover moonshot may present itself as the only way out of this mess.