Term Limits Could Save Community Boards — And Make Them Live Up To Their First Name

Lack of turnover results in boards deeply out of touch with the constituents.

They’re whiter. They’re older. And they’re out of touch.

They’re the city’s community boards — and on Tuesday, you can change them for the better.

The 59 boards are the lowest, yet in some ways, most important, rung of democracy, responsible for vetting matters impacting the district on land-use, transportation, parks, and more. But appointments to the boards by council members and borough presidents are virtually lifetime, meaning members of the boards sit for decades as neighborhoods change around them.

Tuesday’s citywide ballot has three initiatives written by the mayor’s Charter Revision Commission — one of which, Ballot Proposal 3, would cap community board terms at eight consecutive years, yet still allow a member to return after a two-year hiatus [PDF]. The proposal would also require the borough presidents to actively diversify the boards.

Supporters — including Mayor de Blasio, the city council’s Progressive Caucus, Transportation Alternatives, Streetspac, and a coalition of the city’s biggest labor unions — say that the term limits would fundamentally improve community boards in one simple way: members would no longer be de facto permanent appointees, which has, in turn, allowed boards to become deeply out of touch with constituents in their changing neighborhoods.

One need only look at issues related to auto travel, ownership and storage to understand the backward thinking of many community boards.

“Community Board 1 has more car owners than it has non-car owners,” City Council Member Antonio Reynoso told Streetsblog. “We can’t have people on community boards fighting for parking against the interest of saving lives.”

As an example, Reynoso cited the board’s debates over installing bike racks, which have gone on for hours in the past.

That phenomenon reaches far past Reynoso’s North Brooklyn district.

In Morningside Heights, Community Board 9 Transportation Chairwoman Carolyn Thompson has been rejecting bike lane projects for a quarter-century. Most recently, she’s refused to allow a vote on DOT’s plan for traffic-calming on Amsterdam Avenue, where four pedestrians were killed between 2010 and 2016.

Thompson is no stranger to fighting bike lanes. In fact, she took the exact same line against a city plan to install painted lanes on Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard and St. Nicholas Avenue when she served as CB 9 chairwoman in the mid-1990s.

For safe streets activists, perhaps no community board has exemplified that phenomenon in the last year more than Queens Community Board 2, whose leadership spent months fighting protected bike lanes on 43rd and Skillman avenues because they didn’t want to repurpose parking spots for safety. In June, after the board’s transportation committee surprisingly endorsed DOT’s plans, The next day, Rep. Joe Crowley came out against the proposal and, later that week, the board voted it down.

A few weeks later, Crowley was defeated for reelection by primary challenger Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who was “agnostic” on the bike lane issue and won all but one precinct along the bike lane route. Two weeks later, the mayor announced the lanes would be implemented regardless.

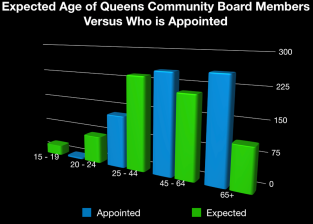

Demographics put the disconnect between CB 2 and its constituency in clear context, according to data research and compiled by pseudonymous Queens activist Diedrich vanVlissingen. The district is 62.3 percent non-white; the composition of the community board itself is 64 percent white. Just 42 percent of district residents are over the age of 45 — compared to 72 percent of the board’s membership.

Turnover on the board isn’t terrible compared to others in the city, but a few members have been around for decades. One, Diane Ballek, was just honored for 25 years of service.

“All these neighborhoods have gone through demographic transitions. As these transitions have occurred, you’ve had some board members stay on,” vanVlissingen told Streetsblog. “That’s not to say they’re not doing a good job, but, ultimately, the people who can best represent their constituents are people who represent the constituents themselves.”

The data for the rest of the Queens’ community boards echoes that of CB 2. On a whole, the borough’s boards are white, older, and more male than the borough itself, according to vanVlissingen’s data.

Opponents of Proposal 3, including four of the five borough presidents, argue that term limits would deprive boards of much-needed institutional memory, giving outside interests like real estate developers a leg-up on district residents.

But that’s overstated, said Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, the odd-Beep out. Under the proposal, council members and borough presidents could still reappoint term limited individuals who’ve taken mandatory two-year hiatus.

And the referendum really isn’t that radical: If it passes, starting in 2019, board members would be allowed to serve four consecutive two-year terms, after which they’d have to step down for at least two years. Plus, it would require borough presidents, for the first time, to post board applications online — a practice that is shockingly not uniform across all five boroughs.

And if the “brain drain” is of concern, voters can vote yes on Ballot Proposal 2, which would create a Civic Engagement Commission charged with providing policy expertise and resources to boards, among other responsibilities.

“This is not radical. The sky is not falling,” Adams said. “Far too often, I have noticed that men and women who serve for 20 or 30 years on the community boards, they come with predispositions as communities change.”

The four borough presidents’ concerns about giving developers a leg-up on land-use issues are unfounded, according to Esteban Giron, a tenant activist in Crown Heights who serves as a public member of the Brooklyn CB 9 land-use committee.

“If someone considers themselves to be too important to take two years off to maybe just sit on the [land-use] committee as a [public member], I would question whether their volunteer time is really as selfless as [the borough presidents] would like to believe,” Giron said. “Not having term limits allows longtime board members to develop cozy relationships with City Planning, and City Planning manipulates this process on behalf of the developers all the time.”

Jeremy Rosenberg, who at 26 is Queens CB 2’s youngest member, has crisscrossed the city speaking in support of the term-limits proposal.

“There’s a learning curve when you join, but everyone brings their own unique toolkit to the table,” Rosenberg said. “It only strengthens the community if the CBs have turnover and have a constantly regenerating set of voices. Just because someone is a new appointee, doesn’t mean they don’t understand these complicated processes.”

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer claims she has the matter under control, noting that 360 of Manhattan’s 600 community board spots have turned over since she took office in 2014.

But it’s not enough. CB 2 member Moitri Chowdury Savard, who has served on the board for a decade and could, presumably, serve much longer, will make the very rare move of voluntarily stepping down. She supports the term limits proposal, but told Streetsblog her decision to step down isn’t meant to send a message to her fellow long-serving colleagues. For Savard, it’s simply a matter of good governance.

“If you look at boards — all boards — there [should be] turnover,” she said. “I don’t think the CBs have really had a great process for doing that. If this passes, it will really help that.”

Election day is next Tuesday, November 6. The Charter Commission’s three proposals are on the back of the ballot. To find your polling place, visit the NYC Board of Election’s online portal.

Update: An earlier version of this story had the wrong number of community boards in the city.