Will Any of New York’s Government Watchdogs Lift a Finger to Control MTA Construction Costs?

Despite the incalculable value of the NYC transit system to the welfare of the city and state, no one in government is racing to solve the MTA's cost problem.

It’s been a little more than a month since the Times published its landmark investigation of MTA capital construction bloat, but the agencies charged with exposing public waste and inefficiency aren’t exactly leaping into action.

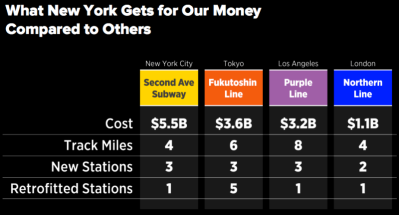

Contrary to the excuses from MTA execs who’ve claimed that NYC is an irredeemably high-cost environment, reporter Brian Rosenthal proved that factors under the MTA’s control diverge wildly from global best practices. Work crews for MTA expansion projects employ four times as many people as the same job would take in other cities. Contractors face little competition and can drive bids far above initial estimates. And a bewildering number of consultants feed at the MTA trough, consuming as much as entire subway expansion projects would cost in other cities.

You can draw a direct line between the MTA’s trouble managing construction and procurement and the sorry state of transit service today. Not only are opportunities to expand the subway constrained, but expansion costs suck resources away from basic maintenance. And evidence compiled by researcher Alon Levy suggests the MTA also spends more per mile on core repairs and upgrades like modern signals than peer transit agencies do.

After seven years in office, Governor Cuomo, who’s pulled in millions from the construction trades for his campaigns, hasn’t uttered a word about the need for MTA cost reform. MTA Chair Joe Lhota has admitted there’s a problem and made some motions toward controlling costs, but forming a task force isn’t the same thing as solving the problem.

If the governor is reluctant to act, there are several oversight mechanisms in New York that are supposed to kick in to keep government honest and accountable. Given the incalculable value of the NYC transit system to the welfare of the city and state, wrenching MTA construction costs into alignment with the rest of the world is arguably the most important good government reform New York’s watchdog agencies could pursue right now.

Streetsblog checked in with some of these watchdogs, asking if they plan to investigate the sources of construction bloat Rosenthal uncovered and issue recommendations to cut costs. They would not promise anything.

Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli has conducted 29 MTA-related audits since 2014. None of them have confronted the construction cost problem directly.

DiNapoli may turn his attention to high MTA costs this year — or he may not. “Our next phase of MTA audits is under development,” said spokesperson Jennifer Freeman. “I can’t provide any specifics at this time.”

As a politician who has to face the voters every four years, DiNapoli is probably the most persuadable officeholder I contacted. Freeman welcomed feedback in our exchange, and a strong dose of public pressure while DiNapoli’s auditors figure out their next target could spur some action. (General contact information for the comptroller’s office is at the bottom of this page.)

Next up on the list was the Authorities Budget Office, a state agency charged with monitoring New York’s numerous public authorities, of which the MTA is the most important and conspicuous. It’s run by Jeffrey Pearlman, appointed by Cuomo last July after a stint as chief of staff to Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul (and before that, chief of staff to the State Senate Democrats).

The ABO may or may not be investigating MTA construction waste, the press office said:

The ABO is aware of the news articles that you mention in your email. That said, as a matter of policy the ABO does not publicly disclose any planned or potential reviews of public authorities or the potential scope of any such review until the final report is released to the public.

I also contacted the office of MTA Inspector General Barry Kluger, appointed by Eliot Spitzer in 2007, who oversees a slate of investigations to root out fraud and abuse every year but never pulled together a coherent explanation of construction waste like Rosenthal’s. There is no discernible email address or press contact on the MTA IG website. A phone message yesterday went unreturned.

An email to Attorney General Eric Schneiderman’s office asking whether he’s opening a criminal investigation into potentially fraudulent conduct did not elicit a response either.

The comptroller and the ABO are the main external entities that should be routinely monitoring the MTA’s construction practices. Is it too much to expect a straight answer about such a consequential problem?

John Kaehny, director of Reinvent Albany, which advocates for transparency in state and city government, said requests about investigations into a particular topic should at least set off a clock at the watchdog agencies, with a firm response taking no more than a couple of months.

“We really don’t know what happens to the requests for audits or investigations we send to government oversight bodies,” he said. “They don’t provide a time frame for when they might start or finish. We have no idea whether they are doing nothing or undertaking the best investigation of all time.”

That brings us back to the headline of this piece. Will any of New York’s government watchdogs lift a finger to control MTA construction costs? We have no idea.