For Politicians, Congestion Pricing Is an Exercise in Delaying Gratification

For congestion pricing to work as policy and as politics, it has to be made out of strong stuff.

Sometime in the next month or two, the Cuomo administration is expected to release its congestion pricing plan for New York City. This is when the politics of putting a price on driving get difficult.

A well-crafted congestion pricing plan is a lock to relieve the burden of excess traffic on city streets. There’s a reason every city that has adopted a cordon toll system has decided to keep it.

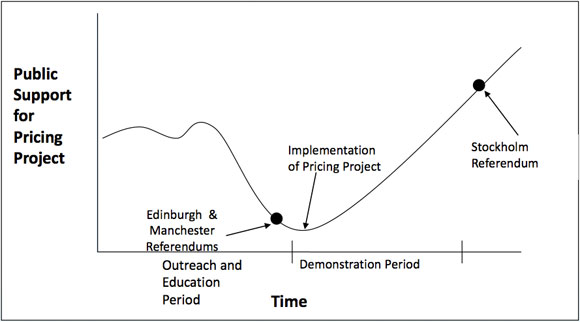

But some cities never find out, because they get mired in what Stockholm transportation director Jonas Eliasson calls the “valley of political death.” As congestion pricing gets more attention in public discussion, people can clearly envision the cost of tolls, while the benefits of less traffic and better transit remain intangible or uncertain.

This is the moment when congestion pricing referendums in Manchester, England, and Edinburgh, Scotland, failed. Residents never experienced the benefits of congestion pricing, and they voted against it.

In Stockholm, city officials first instituted congestion pricing as a seven-month trial, followed by a public referendum. Before the trial, public approval stood below 40 percent. Seeing traffic evaporate overnight transformed perception of the policy, which cleared the referendum with over 52 percent of the vote.

By 2011, support stood at nearly 70 percent. The proof was in the pricing.

In London, congestion pricing was enacted in 2003 without a trial or a referendum. It was a signature policy initiative of then-Mayor Ken Livingstone. At the time, Livingstone’s proposal to charge drivers to enter the city center was widely panned by politicians and the press.

Then the fees immediately reduced congestion 16 percent. After eight months with the charges in place, public support had gone from around 40 percent to a majority. While traffic speeds have since fallen, the reduction in car volumes has enabled the city to repurpose street space for walking, biking, and transit — creating a much safer and more efficient surface transportation system.

In New York, polls consistently show support for congestion pricing in the 40 percent range, including the latest survey from Quinnipiac, released in early October. This is in line with public opinion in Stockholm and London before implementation. (Earlier Quinnipiac polls in 2007 and 2008 showed a surge in support for tolling “if the money were used to prevent an increase in mass transit fares and bridge and tunnel tolls” and “if the money were used to improve mass transit in and around New York City.”)

For Andrew Cuomo and the other politicians who’ll be creating congestion pricing policy, there are a couple of major takeaways.

One, they have to be prepared for some rough moments on the way to implementation. Making congestion pricing happen requires delayed political gratification — the big public approval payoff only comes once people can experience the benefits in real life.

Two, their plan has to be technically sound. As Eliasson said at a recent event at TransitCenter, policy making is “really the job for experts.” The political instinct to carve out exemptions and seek other points of compromise is actually a losing proposition, because it will weaken the impact — and that will dampen public support after implementation.

For congestion pricing to work as policy and as politics, it has to be made out of strong stuff.