When People Can’t Afford Transit, New York City Pays for It — One Way or Another

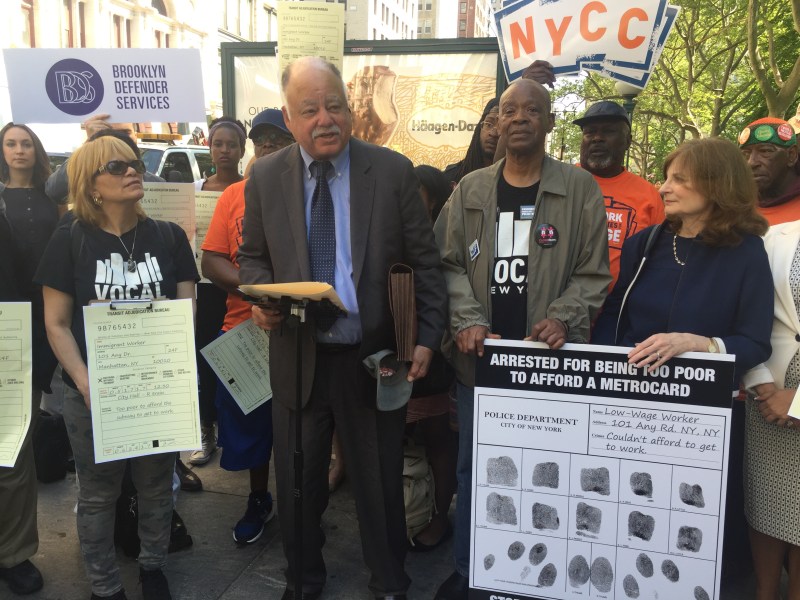

MTA Board Member David Jones talks transit affordability: "The only group that really isn’t getting any help seems to be the working poor."

The City Council passed an $85 billion mayoral budget this month without “Fair Fares,” the $212 million proposal to provide half-priced transit fares to New Yorkers living below the federal poverty line. Mayor de Blasio declined to fund even a pilot of the program, citing cost and insisting discounted fares are the responsibility of the state, which controls the MTA.

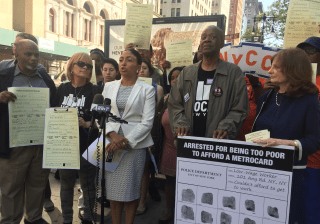

Meanwhile, poor New Yorkers continue to hop turnstiles, often out of necessity, and often with dire consequences. As a mayoral appointee to the MTA board, Fair Fares advocate and Community Service Society CEO David Jones has sounded the alarm on the over-policing of fare evasion, which results in around 30,000 arrests each year. Of those arrested, around 90 percent are people of color.

Streetsblog spoke with Jones yesterday about the city’s growing transit affordability crisis, and the next steps for the Fair Fares campaign. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You spoke outside City Hall last week in support of Council Member Rory Lancman’s legislation that would require the NYPD to make its fare-beating arrest data available to the public. Why?

I had been appointed to the board with the understanding that I was going to be focused on the needs of working poor people trying to use public transit. As I’ve said before, this is a crime of poverty. This is our version of Victor Hugo’s stealing bread. And to prosecute individuals for this, and get them tied up into the criminal justice system, seems to be a particularly poor use of scarce resources.

Transit police report on a number of other arrests on a monthly basis, but fare-beating didn’t quite have the attention that we thought it should. We think the Lancman legislation will lay out, across the system, which stations seem to have the highest numbers of people engaged in “fare evasion.” At least from a preliminary look, it concentrates in two different areas: in major transfer points and in the poorest communities in the city.

You’ve said that fare-beating enforcement “has become the main work of the transit police.” Is this a new phenomenon?

Subway costs have accelerated well beyond cost of living increases. Those earlier fare increases led the MTA to keep to a more regular biannual two percent increase, but people are still dealing with the surge that took place over the last decade. CSS does a large survey call the Unheard Third, and the issue of transit affordability for the working poor has emerged as one of the critical issues that have come forward.

I’m so old, I remember the time when the subway fare was 10 cents. It doesn’t seem like much — “Oh, $2.75, no big deal” — but if you’re working an eleven dollar-an-hour, twelve dollar-an-hour job, and you have a family you’re trying to get someplace, or you want to go somewhere on the weekend, you don’t have a car, this can become a really enormous impediment to getting around the city.

The statistics we’re picking up in our survey work indicate that this is becoming more and more of a problem. We’ve done “reverse Robin Hood” on the transit system. The people who get the biggest discounts are the ones who can afford the monthly pass, which is about $121. If I’m working as a domestic worker or as a security guard, I can’t come up with that amount of cash as a lump sum.

But if you have a big enough income, and a big enough employer, you get something called TransitChek, which adds benefits on top of that. And then, of course, if you’re elderly, whether you’re Michael Bloomberg or me, you get a not-means-tested half-priced fare. Same for disabled people. There’s also a free pass for young people going to school, which is not means-tested either. So if you’re going to Brearley or one of the fancier schools, with a millionaire parent, you get a pass too. The only group that really isn’t getting any help seems to be the working poor.

You’ve called fare-beating arrests a “disturbing use” of NYPD officers. What do you mean?

This is not an attack on the NYPD. I think if you did a poll or a survey of subway riders, they’d much more be interested in keeping them safe on the platform than making the police’s main responsibility fare evasion. The NYPD uses resources in the areas of high crime, and that makes sense. But the result is that you see emphasis on the communities with the highest poverty rates, and that becomes one of the reasons for the enormous numbers of arrests, particularly of people of color.

These communities need police protection, no question about it, but we’d like to see a shift of focus away from this “broken windows” problem to something else. At the very least, we’d like NYPD to do more about deterrence. We put big ads all over the place that say: “Don’t smoke because this is what can happen to your insides.” I think a similar campaign that says “This is what can happen to you if you get arrested for fare evasion.” If we are serious about trying to cut down on the numbers of, particularly younger people, who are brought into the criminal justice system, we must at least do more in terms of deference.

What do you say to people, MTA officials and members of the public, who see fare evasion as a major concern, particularly in terms of maintaining revenues for the agency?

The argument that they’re trying to save the system money really doesn’t make any sense. If someone can’t afford $2.75, they certainly can’t afford to pay a $100 fine. Scott Stringer actually did an audit showing the collection rate for these efforts is less than 50 percent.

I think it’s understandable that people want [others to pay their] fair share, but when people don’t have any money and are desperate, we want them to work, not go back on welfare. These people are trying to get to low-paid jobs. I think everyone in the public recognizes that if you don’t have people working, you have real trouble — real taxpayer problems.

I’m not calling for an end to enforcement, I’m calling for something to dramatically lower the numbers of arrests. I’m not [saying] it’s a free subway system — it’s not. I think most reasonable people after they start to look through the numbers, recognize that we have to do something a little less aimed at arresting people, and more aimed at deterrence.

One of the things I’ve noticed is the total shock, across the board, when people start to hear the numbers. To have this as the leading arrest in the subway system when riders are worried about being pushed in front of trains or controlling potential problems with overcrowding — this is not what they want NYPD to be focused on.

Your organization put forward the Fair Fares program as one possible solution to this problem. Why do you think Mayor de Blasio declined to fund the program?

We’re not quite sure. It seemed to be a couple of things. First, they felt the cost was high — to fully implement what we were suggesting for people below the poverty line, it hovers around $200 million.

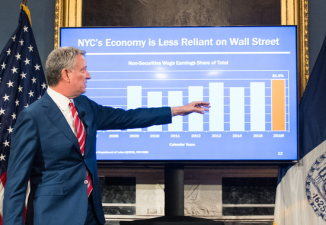

But, at least to phase it in — it wasn’t a huge hit on the budget. On top of that, there’s an explosion of people using the ferry service that the mayor inaugurated. It is perhaps the deepest subsidy for ferries of any city in America. The city subsidizes, essentially, some of the richest parts of New York — I don’t mean they’re hugely rich, but these are commuters living by the waterfront, not people who are living in NYCHA. They’re getting this deep subsidy, far more than the subsidy we were calling for for people below the poverty line.

We also have not been able to convince the mayor that this is not a subsidy of the MTA, but rather a direct subsidy for poor people. It goes directly into their pockets. It means $700 a year, almost as much as the entire EITC program, to people living below the poverty line.

What impact can the Fair Fares campaign have in shifting how the public views public transit?

In our polling, upper-income people understand they want a better system, but they also understand that in order to get people who are supporting this incredible city as dishwashers, as childcare workers, in hospitals, as orderlies, we’ve got to be able to get to work, and make this city actually operate.

It’s not only the hedge fund managers who make this city operate, and the poor are pushed further and further to the periphery of the city because they can’t afford the areas that are closest to the hub. They need public transportation, subways and buses, perhaps more than any other group. So as we plan a new transit vision for the city of New York, we must also understand the vital necessity of having access for the working poor.

We didn’t get Fair Fares this year, but this is just the first act for us. I’m on the MTA board until 2020. Our efforts on paid sick leave, which the mayor ultimately embraced, took three years to succeed. We’re going to continue to persist on this issue because we think it’s so fundamental to an equitable city.