Are the Subways Getting Worse? Depends on How You Measure It

Yesterday the Straphangers Campaign released a report that shows the number of subway incidents that result in a significant delay in 2013 rose 35 percent from 2011. “The increase in alerts is a troubling sign that subway service is deteriorating,” said Gene Russianoff of the Straphangers Campaign.

The MTA responded that despite the report’s findings, the reliability of service has remained steady over recent years. “Since 2011, the amount of time customers have had to wait for a train throughout the system has remained flat,” the authority said in a statement.

Why the discrepancy, and who is right? They both are, but they each used a different metric to reach their conclusions.

The Straphangers report used a novel metric to come to its conclusions: It tracked the number of alerts the MTA sent out via text message and email warning customers of delays.

According to the MTA, “Email alerts are issued for any incidents reported… that will result in a significant service impact expected to last 8 to 10 minutes or more.”

The Straphangers Campaign documented each actual incident of delay over eight minutes that was caused by events such as signal or mechanical problems. The report distinguished between “uncontrollable” delays, those involving a sick passenger or police activity, and “controllable” delays.

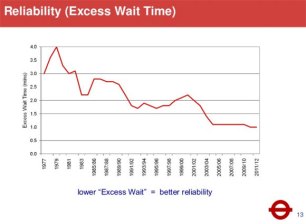

The MTA, on the other hand, uses “wait assessments” to track the level of service. Wait assessments measure headways, or the time between trains, and track whether the next train arrives within a certain time period after the previous train departed — in this case the delay cannot be more than 25 percent longer than the scheduled headway. In other words, a train with an expected headway of eight minutes is considered on time if it arrives within ten minutes.

According to wait assessments, MTA subways have improved on-time performance slightly since 2011.

It is also worth noting that the MTA’s wait assessments are based on a sample. On most subway lines observations are made by humans rather than computers, meaning it is impractical to monitor on-time performance for every train. The numbered lines use data from their signaling systems, which can track when a train passes a certain point.

There are other drawbacks to wait assessment as a metric. It does not account for train “bunching” that affects an entire line, and it also does not reflect the severity of a delay.

The takeaway is that train service overall seems to be holding steady. However, the number of unscheduled delays is increasing, perhaps as a result of deferred repairs and an underfunded capital program.