The Fulton Street Mall: Retail Success on NYC’s Original Transitway

As the New York Post continues its increasingly tedious assault on pedestrians and crosstown transit riders, its writers always seem to suggest that giving priority to buses in an important retail area is both radical and self-evidently bad for business. If they bothered to look just one borough away, they’d see that nothing could be further from the truth. The eight bus- and pedestrian-only blocks of downtown Brooklyn’s Fulton Mall make up the most successful retail strip in the city outside of Manhattan.

It was a similar bus- and pedestrian-only plaza that the DOT scrapped for a single block of 34th Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues — partially, it seems, at the behest of Macy’s and local real estate interests. So it’s revealing to compare the current clamor over the 34th Street plaza, the 34th Street transitway, and now, in the Post at least, any transit improvements whatsoever, to the creation of the Fulton Mall.

The Fulton Street Mall has its roots in the planning vogues and racial turmoil of 1960s New York. “The idea of a transit mall was what every downtown revivalist was talking about in the 1960s,” explained Meredith TenHoor, the co-author of Street Value: Shopping, Planning and Politics at Fulton Mall. Prompted by department store owners worried about retaining their white customer base, she said, the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership proposed a series of improvements to make the area “feel more like an indoor shopping mall instead of a dirty downtown street.”

Over time, however, the design morphed — in some ways unintentionally — from one intended to compete with Long Island shopping malls into one that embraced its Downtown Brooklyn location. According to a 1977 article in the New York Times, for example, plans for a Plexiglas arcade covering the street were scrapped by the time construction started.

More important was the inclusion of buses in the plan, a consequence of the budget realities of the fiscal crisis years. “The city had no money at the time,” said TenHoor, “so they were able to use federal transportation grants to make the pedestrian mall” by adding a transit corridor. It helped that as the city’s planners studied the area, “they found it had all these incredible links to transit and most of the shoppers were coming through transit.”

Of course, the suburban concept never disappeared entirely. According to TenHoor, the department stores also built a series of large parking garages behind Fulton Street in order to try and attract shoppers heading out to suburban malls.

Politically, the Fulton Mall was relatively uncontroversial. While a Lindsay Administration plan to pedestrianize Madison Avenue was defeated by the Board of Estimate (at the hands of future mayor and then-comptroller Abe Beame), Brooklyn Borough President Sebastian Leone and the taxi industry, both Beame and Leone supported the Fulton Street project.

The Fulton Mall’s smooth path through city government was in large part paved by the strong support of large downtown Brooklyn retailers. A senior VP at the department store Abraham and Straus, for example, told the New York Times that the plan would create a “pedestrian paradise.”

Though TenHoor said their support didn’t drive the project forward, many smaller merchants also supported the plan. In a 1973 article headlined “Small Merchants Hail Brooklyn Mall,” the Times quoted Jack Gindi of Joy Gifts as saying the plan would improve sales by “bringing more people in who will feel more relaxed to stroll and window-shop without the crowding and hazards of traffic.”

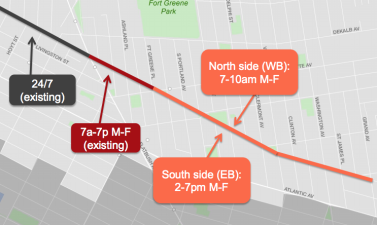

Integral to winning business support, said TenHoor, was ensuring that deliveries could be made. “That was the first thing that the planners of the street did to get businesses on board.” In many cases, they developed delivery routes on the side streets, she said, though delivery vehicles are currently allowed on Fulton Street between 7 p.m. and 7 a.m.

Today, the Fulton Mall is one of the most successful retail streets in New York City. Rent for retail is more expensive than anywhere else outside of Manhattan, according to industry data. “It is a point where all of this transportation converges and people come from all over Brooklyn to shop,” said TenHoor.

“Pedestrianization really helped things because it made things feel more welcoming,” continued TenHoor. The extra space makes the street more comfortable and creates room for activities not possible on narrow sidewalks. “There’s actually ample public space for culture to take root,” she said. “It’s quite important for the people who shop there.”

Any comparison between the Fulton Mall and the abandoned plans for 34th Street isn’t apples-to-apples, of course, but the concepts were fundamentally similar. Prioritizing bus riders and pedestrians along Fulton Street earned strong political support and has proven popular for shoppers and profitable for retailers. What’s so different on 34th Street?