New Law Requires ‘Daylighting’ At 100 Intersections Each Year — After ‘Study’

The Department of Transportation must study the safety benefits of “daylighting” and implement the street safety measure that helps improve visibility at a minimum of 100 intersections each year — starting in 2025 — thanks to new legislation passed on Thursday by the City Council.

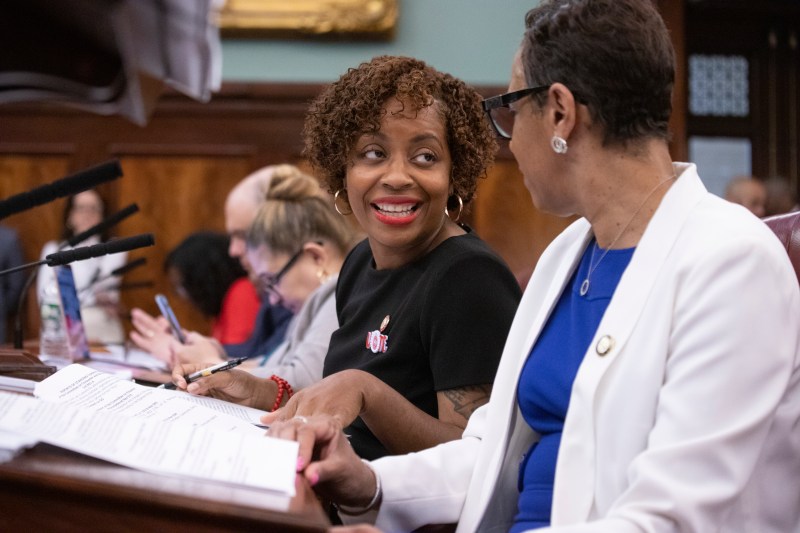

Council Member Selvena Brooks-Powers (D-Queens), who chairs the transportation committee, introduced the bill last year, when 16 kids were killed in traffic violence, a record high in the Vision Zero era.

“Last year was the deadliest year on our roads for children since 2014,” Brooks-Powers said at a rally outside City Hall ahead of the vote. “Daylighting is a proven safety measure that expands sight lines at intersections, where traffic violence often seems to take place.”

The Council voted 40-7 for the bill — which came after the high-profile killing of 7-year-old Dolma Naadhun by a reckless driver at Newtown Road and 45th Street in Astoria, which lacked daylighting to allow for more parking. Days after her death, the DOT remedied the crosswalk by filling in the missing paint, but a trio of elected officials, including Brooks-Powers, called on the city to do more along the entirety of Newtown Road.

“Traffic calming measures must be implemented immediately to prevent further loss of life,” the three pols wrote in a Feb. 20 letter to DOT.

The seven “no” votes were from Council Members Ariola (R-Queens), Borelli (R-Staten Island), Carr (R-Staten Island), Kagan (R-Brooklyn), Paladino (R-Queens), Vernikov (R-Brooklyn), and Yeger (D-Brooklyn).

Today, the Council passed legislation (sponsored by @CMBrooksPowers) to require @NYC_DOT to implement daylighting to improve sightlines and safety for all road users by preventing vehicles from occupying certain spaces near the intersecting streets. pic.twitter.com/T2RNhTuCm3

— New York City Council (@NYCCouncil) April 27, 2023

Across the river in Hoboken, officials tout daylighting as one of the reasons the city hasn’t had a traffic fatality in more than four years.

But in New York, city officials were initially opposed to the bill, arguing that they supported it in “spirit,” but that it would ultimately limit the agency’s flexibility. And DOT Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez said during a hearing back in February that removing parking without replacing it with another physical obstruction such as a bike rack or flex-posts actually has the opposite effect by encouraging drivers to take faster turns.

“Daylighting … must be implemented with physical infrastructure in the newly opened space to prevent vehicles from turning more quickly. We would like to retain flexibility to determine which treatments are the most appropriate in each location,” said Rodriguez, who introduced similar legislation back in 2015 to implement daylighting at 25 of the city’s most dangerous intersections each year. It never made it out of committee.

But the DOT later came on board with Brooks-Powers’s bill after it was amended to include provisions that DOT first “study” the effects of daylighting, and that installation wouldn’t begin until 2025. The updated version also includes a modification that requires the city to “install daylighting barriers” at intersections where daylighting has already been implemented — a change meant to satisfy Rodriguez’s earlier reservations.

“I believe daylighting, especially when implemented with physical features, can prevent injuries and death in New York,” Brooks-Powers said.

Brooks-Powers’s legislation was passed along with two other street safety bills, including:

- Intro 679: Would require the DOT to annually install at least one traffic-calming device on at least 50 blocks adjacent to senior centers or naturally occurring retirement communities unless “doing so would endanger the safety of motorists or pedestrians, or would be noncompliant with the Department’s traffic control device guidelines.”

- Intro 805: The DOT would be required “to accelerate the schedule in which the agency conducts the study of traffic crashes involving a pedestrian fatality or serious injury required by local law from every five years to every three years.