Has the state penned itself in on Penn Station?

State officials recently insisted in court filings that Gov. Hochul and her disgraced predecessor’s plan to give a powerful donor a $1.2-billion tax break to build 10 skyscrapers around Penn Station never intended to fully fund the $20-billion renovation and expansion of the transit hub — an assertion under oath that calls into question her election-year pledge to “generate the revenue we need to fund the transformation of Penn Station.”

Fifteen months later, that pledge appears all the more foolish as developer Steve Roth has repeatedly expressed skepticism about the short-term prospects for office development in Manhattan post-Covid. But Hochul hasn’t changed course and, indeed, is rewriting history, claiming the goal of fully funding the new Penn Station with tax money from Roth’s development died when Gov. Cuomo left office.

“The former governor’s perspective lost relevance upon his resignation,” ESD officials wrote in court documents submitted last month in response to a suit to stop the plan by area tenants and property owners. “Other funding sources will be needed to pay most of the $20-billion cost” of a new Penn Station.

The “primary purpose” of the project, officials said, is to “effectuate the 10 buildings” and $2 billion worth of “civic improvements.”

The agency’s lukewarm pledge to provide “some” funds for Penn’s $7 billion renovation and $13 billion southern expansion — dubbed “Empire Station Complex” by officials — is belied by the project’s history, starting with former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who said the redevelopment would pay for a modern station.

“The current block south of Penn has a number of real estate holdings,” the former governor explained during a speech to business leaders in early 2020. “The state will plan to acquire it for public use. … The funding for Empire Station Complex will come from the revenues that are generated there.”

Cuomo’s $22 billion vision featured three components — a $7 billion renovation of existing Penn Station, a $13 billion expansion of eight new tracks south of the station to carry additional capacity when a new tunnel under the Hudson River finally opens, and the $2 billion Vornado-supported “public realm” improvements, which include three renovated subway stations and new Penn Station entrances in five of Roth’s buildings.

Of course, that was pre-Covid. Since then, Roth and Vornado have made it clear that they have no short-term plans to build. “Capital markets are now making it almost impossible to build new. … Friday is dead forever, Friday is going to be a holiday forever. Monday is touch and go,” Roth, who turns 82 this year, told Vornado shareholders last month. “Our strategy here is to achieve very strong returns on rents well below those required for new construction.”

Given that vocal reluctance to build, even the $3.4 billion to $5.9 billion the state expects to raise from taxes on Roth’s new buildings are decades away. State officials, however, are sticking to the Cuomo blueprint — handing a massive tax break to a well-connected donor with limited benefit to the public.

Vornado and NY State: Too close for comfort?

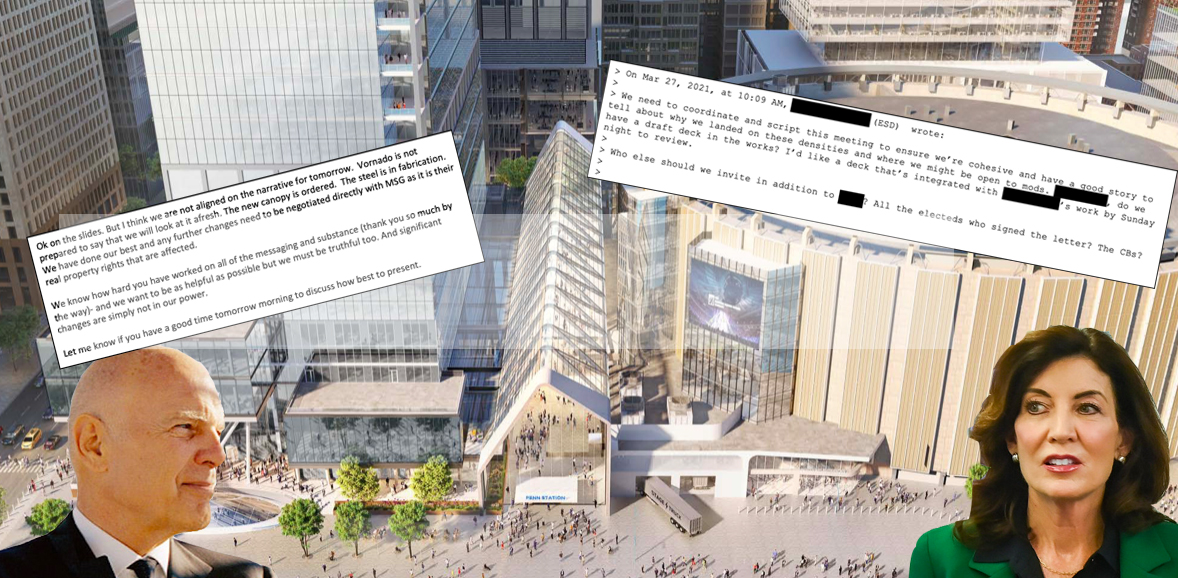

Roth gave maximum donations to Hochul’s re-election campaign last year and was also a political backer of both Cuomo and former President Donald Trump. Perhaps not coincidentally, his real estate company had special access to the state’s efforts to sell the Penn Station redevelopment to the public, according to internal documents obtained via FOIL and submitted as evidence in court by the project’s opponents. The company used that direct access to influence the projects — while taking the lead on key aspects of ESD’s public outreach, opponents charge.

“The plan wasn’t created for Vornado,” said Diana Gonzalez of the group Trains Before Towers, a coalition of tenants and property owners opposed to the project. “It was created by Vornado, pretty much every step of the way.”

Emails between Vornado and ESD show years of collaboration between the two entities, with state officials often seeming to defer to the developer’s advice and preferences. Between January 2020 and October 2021, the two entities met in person or over the phone every 2.1 days, according to call logs and schedules obtained by opponents via FOIL.

Vornado and ESD “coordinated” on “narrative” ahead of public meetings, emails between them show – with the developer often calling the shots. In one instance, in February 2021, ESD sought Vornado’s advice for how to defend the proposed heights of the project’s hypothetical 10 skyscrapers. Vornado officials responded with a cache of materials including a powerpoint “making the case that… you need the most density here.”

“We need to coordinate and script this meeting to ensure we’re cohesive and have a good story to tell about why we landed on these densities,” a top ESD official wrote in an email dated March 27. On another occasion, ESD asked Vornado to “look afresh” its plans for a new Penn entrance at 32nd Street and Seventh Avenue — only to back down immediately when the developer expressed reservations about committing to do so publicly.

“We are not aligned on the narrative for tomorrow. Vornado is not prepared to say that we will look at it afresh,” one company official told ESD, while another replied they would “do the dancing” to fit ESD’s “narrative” of reevaluating the strip.

“LOL I appreciate that,” the ESD official replied, “but really didn’t mean you guys have to offer to look at it afresh.”’

Roth also put an initial deposit of $1 million, at least, into an special account to cover “all costs for legal services, environmental review, neighborhood conditions studies, appraisal services, architectural service for above-grade project site planning, and financial advisor services,” according to a Feb. 3, 2020 cost sharing agreement with ESD.

The government agency and private developer agreed to “cooperate to obtain efficiencies … and avoid duplication of efforts,” according to the agreement, also obtained by opponents via FOIL.

‘Their essential self-interest’

Vornado’s close relationship with ESD should cast further doubt on the value of Hochul’s proposed rezoning, according to one former top New York transportation official.

“This series of emails indicates how the Cuomo administration put development before the public’s long term self-interest. The negotiation was for the purpose of real estate development — as opposed to all the things you’d want to do for the public,” former Port Authority Executive Director Chris Ward told Streetsblog.

“You have the developer doing largely all the work for a transportation plan where their essential self-interest is their development.”

Academic research points to the potential for corruption when political donations and government subsidies are involved. One 2021 study by researchers from Penn State and Georgetown found firms that make campaign donations to elected officials are four-times more likely to receive government subsidies. Another report from the same year found that US companies who receive state subsidies are more likely to engage in corruption.

In the case of Penn Station, Govs. Cuomo and Hochul set up a donor with a sweetheart, tailor-made deal gift-wrapped with tax breaks and eminent domain seizures.

Instead of paying taxes on its developments, Vornado will provide the state discounted annual “payments in lieu of taxes” (aka PILOTs), but the state’s ability to collect that money requires Vornado to build — and that’s likely to take “over the next 20 years or more,” according to ESD’s own calculations. The state Public Authorities Control Board approved the plan last July — with caveats that state cannot borrow money for the streetscape and subway improvements until the control board approves site-specific, individually negotiated PILOTs. Those agreements would require Vornado to have plans to build.

Despite Cuomo’s earlier pronouncements that the plan would fund a Penn rebuild, an outside consultant’s financial analysis found the proposed PILOTs would raise, at most, $5.9 billion, $2 billion of which would fund the public realm improvements including — in ESD’s words — Penn Station entrances at five of the development sites, the renovation of three subway stations, “an underground pedestrian network” widened sidewalks, “open space” and “other improvements.”

A decades-long building process will delay the PILOTs, according to critics — and require the state to pay the cost of “interest support payments” on the loans it draws on the project. Such was the case with the Hudson Yards redevelopment: the developer, Related Companies, ultimately paid back the costs of the interest payments, but only after taxpayers were on the hook for hundreds of millions of dollars.

State officials in court documents insisted Vornado’s buildings don’t need to be built right away for the PILOT money to become available in the budget for the urgent transit needs. But much subway and “public realm” improvements cannot physically happen without the construction of new towers, and the amount raised will cover a tiny portion of the the cost of $7 billion Penn renovation and $13 billion southern expansion.

How to pay for a new Penn?

Hochul called the $7 billion gut-reno an “urgent priority” when she endorsed it in 2021, promising a four- or five-year construction timeline.

“This’ll fund the reconstruction, the future expansion, as well as the public realm around it,” she said at the time.

But until PILOT agreements are reached, the state can’t even borrow money for the project — leaving taxpayers with the initial bill and an IOU from Roth, whose property gets added value courtesy of the tax subsidies and any transportation and public space changes the state manages to make happen.

“The premise of this project is that the towers are necessary to underwrite the cost of Penn Station, but Roth isn’t under any obligation to begin construction and until he completes it there will be no revenue to underwrite Penn Station, in other words the project won’t have done what it was built to do,” said Chuck Weinstock, an attorney representing project opponents.

“The value of Roth’s land will have grown exponentially. That value goes up regardless of whether he builds or not. He gets a lot, and we get nothing.”

Critics have longed questioned the cozy relationship between ESD and developers in advancing rezoning projects such as Hudson Yards and Atlantic Yards. In court filings, ESD’s attorneys defended the state’s relationship with Vornado as “consistent” with state law directing the agency to “afford maximum opportunity for participation by private enterprise.”

“ESD often works with private developers in planning its projects because their involvement — and private capital — are critical to the projects’ success,” ESD’s attorneys from the firm Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner claimed. “Because Vornado owns or holds an interest in five of the eight development sites in the project area, ESD has involved this developer in its planning activities for these sites since the inception of the project. It has done so because of the critically important role that Vornado will play in the success of a major portion of the project.”

A Vornado spokesman referred Streetsblog to the company’s own recent filings in the suit against the project, in which the developer argued that the project’s extended construction timeline — 22 years, according to Vornado — necessitates advanced planning in the form of the General Project Plan.

“The GPP is the first step in this process — essentially a rezoning — that is necessary before any other step can be taken,” Vornado Vice President Barry Langer said in an affidavit submitted to the court. “The first buildings anticipated to be built pursuant to the GPP — the buildings proposed for Sites 1, 4 and 7 — are assumed to be completed over an 11-year period (i.e., by the end of 2033).”

A rep for Hochul said the state is staying the course.

“Gov. Hochul has proposed a vision for Penn Station that provides a new, revitalized station, in addition to more station safety and platform access, more housing, more transportation options, more open space, and more services for the surrounding neighborhood,” spokesman Justin Henry said in a statement. “The Governor’s proposal is the responsible, commuter-first plan that New Yorkers deserve and is befitting of Penn Station’s status as the busiest transit hub in the Western Hemisphere.”

But with nothing set to be built on the sites in the near-future, any suggestion the state can raise money in the short-term from the project is “delusional,” said Rachael Fauss, policy analyst at government watchdog Reinvent Albany.

“They literally cannot bond until a PILOT agreement is reached,” Fauss said. “Before COVID people were skeptical this would raise any money. After COVID, it’s delusional.”

At least one prominent official — Sen. Leroy Comrie, who represents the State Senate majority on the PACB — appeared ready on Friday to scrap the plan and figure out a new way forward.

“We all know, everyone in the state knows, that the GPP that’s been presented is not longer working,” Comrie (D-Queens) implored the MTA’s Leiber during a Senate hearing in Manhattan on Friday. “I would just appeal to you to simply reset. We need Penn Station to work properly, we need Penn Station to be running.”