R.I.P. DOLMA: A Deep Dive on DOT’s Daylighting Dilemma

City workers on Thursday made minor safety improvements at a dangerous intersection where a driver killed a 7-year-old girl last week, but the paint job could not cover over a raging debate about the city’s decision to not provide full visibility — called “daylighting” — at tens of thousands of intersections where the next victims will be walking.

In the short term, the Department of Transportation said it would immediately improve a crosswalk marking at Newtown Road and 45th Street in Astoria, whose crosswalk had been truncated to allow additional parking (note the temporary paint in the picture below to indicate where new paint was slated to be added). The agency said it would also review other possible improvements at the intersection, including daylighting):

Earlier this week, Streetsblog reported that the intersection where Dolma died once had much more daylighting, but lost it when the DOT repaved the street and repainted the crosswalk to be incomplete on one side.

The first steps on Thursday will not be enough for three key City Council members, who wrote to the DOT earlier this week demanding deeper improvements. The letter from area Council members Julie Won and Tiffany Cabán, plus Transportation Committee Chair Selvena Brooks-Powers, called for daylighting at three additional intersections on Newtown Road, plus “neckdowns to increase visibility of pedestrians,” speed bumps, additional stops signs and reflective street markings “at all streets on Newtown Road.”

“Nothing can bring back Dolma Naadhun, but we can prevent further loss of life so that no family must experience the loss of a loved one,” the trio of lawmakers wrote.

Our Tibetan community is mourning the loss of 7-year-old Dolma Naadhun during what should be a joyous time celebrating Losar. @NYC_DOT must implement safety measures at Newtown Road & 45th St to prevent further deaths & injuries. Read our joint letter @CMBrooksPowers, @CabanD22. pic.twitter.com/QVEA8QfJOi

— Council Member Julie Won (@CMJulieWon) February 22, 2023

State law bars drivers from parking within 20 feet of a crosswalk, but the state also gave New York City permission to exempt itself [see Section 4-02(e) in this PDF] from enforcing that provision, which has allowed the city to maintain free parking spaces for privately owned vehicles in the public right of way — right up to the edge of pedestrian crossings. Here’s what that looks like:

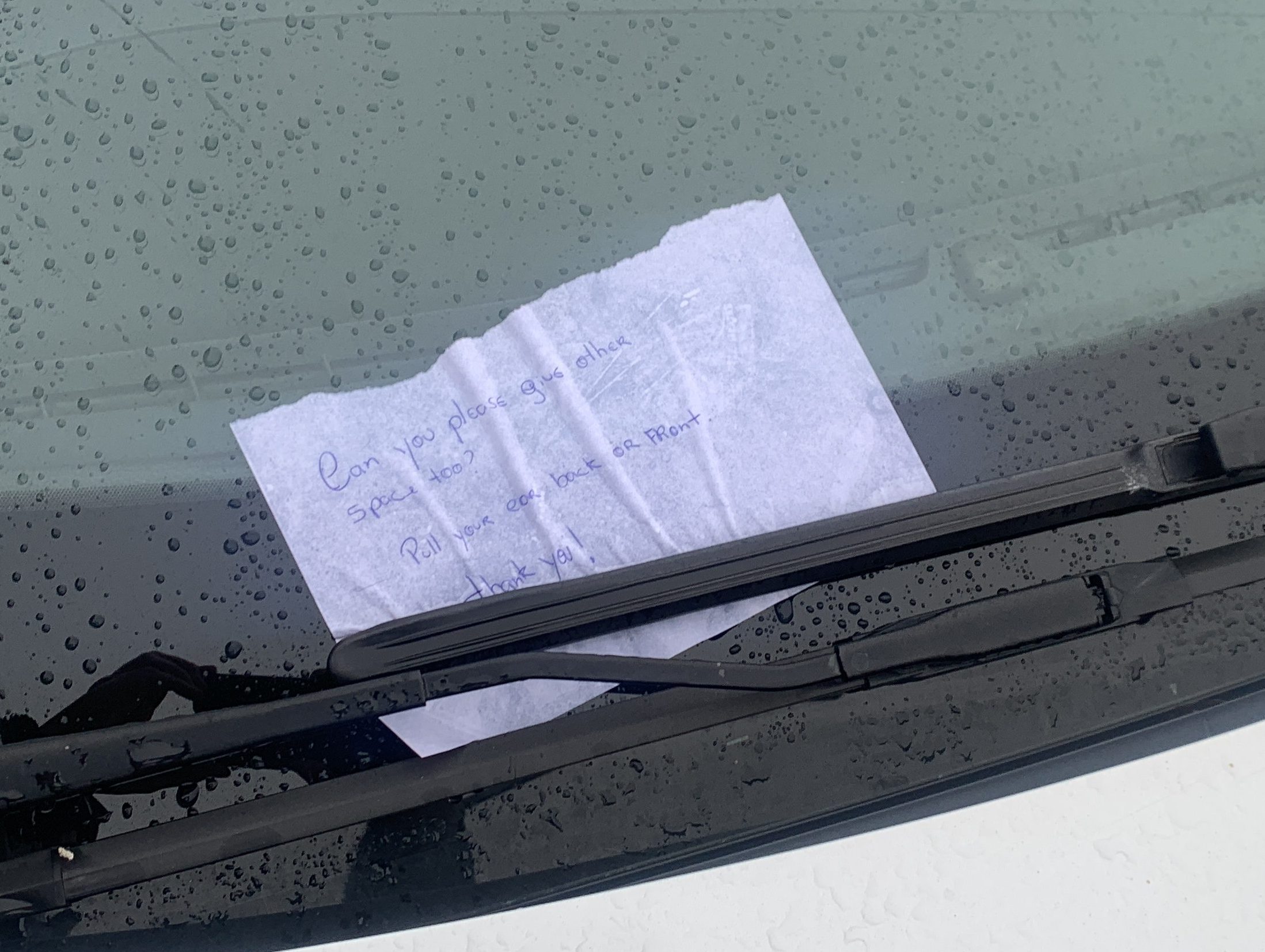

Indeed, when drivers don’t fill the legal space left by the city, they get notes on their cars:

DOT has, of course, daylighted hundreds of intersections in the city, sometimes installing bike racks or other low barriers to both keep the corner clear yet not allow drivers to make fast turns. As an example, many of the intersections on Second Avenue in Manhattan were improved in this manner, as are many turns near bike lanes (see slides below):

But the question keeps coming up: why aren’t all intersections daylighted? Transportation Alternatives, for example, has demanded universal intersection daylighting as part of its NYC 25×25 plan and its “Seven Steps” agenda for Mayor Adams and the City Council.

“By removing parking and using physical infrastructure, such as curb extensions, benches, Citi Bike docks, and bike parking, the city of New York can increase visibility and slow vehicle turning speeds,” the group has said, and provided a graphic to demonstrate the benefits of daylighting.

Daylighting also helps diminutive pedestrians such as children. Here is a typical intersection (this one located in Woodside, Queens) where the Department of Transportation, exercising its authority to supersede state law, has allowed drivers to park directly against a crosswalk. Note first what the intersection looks like from the perspective of a driver:

Now note what the crosswalk looks like from the perspective of a 4-foot-tall child:

The intersection where Dolma was killed on Feb. 17 is a prime example of an intersection that lacks the kind of daylighting required under state law, as TA showed in its graphic:

The answer provided by DOT is that as much as advocates believe daylighting is perfect, it’s not. But then, neither is the DOT analysis of it:

In 2015 the agency examined left-turn crashes at more than 3,000 intersections over the previous four years. The study analyzed the results of having “natural daylighting” provided by a fire hydrant at a corner, without any markings or physical barriers.

The agency sent a screenshot from the study showing some of its findings to Streetsblog more than six months after a Freedom of Information Law request, but has so far declined to provide the full study.

The agency found that such hydrant daylighting provided only minimal safety improvements for pedestrian and bicycle injuries in left-turn crashes. For example, on one-way-to-one-way intersections, the rates of injured cyclists and walkers actually slightly increased at intersections that didn’t have a car parking right up against the crosswalk.

Officials also observed that there were roughly 50 percent fewer injuries at daylighted intersections with stop signs on one-way streets leading to two-way streets. The presence of the stop sign made daylighting more effective because not only did it allow drivers to oncoming traffic and pedestrians, but inhibited cut-through driving that occurred without a stop sign.

The agency emphasized that it has not done a comprehensive study of daylighting.

The main problem with daylighting, the agency concluded from its limited study, is that once a parked car is removed — and not replaced with some physical obstruction such as a bike rack or flex-posts — the greater visibility for turning drivers encourages them to take the corner faster because nothing is blocking the start of their turn.

Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez reiterated this argument at a hearing earlier this month when he revealed that the agency opposes a Council bill that would mandate 100 daylighted intersections every year.

“Daylighting … must be implemented with physical infrastructure in the newly opened space to prevent vehicles from turning more quickly,” he said. “We would like to retain flexibility to determine which treatments are the most appropriate in each location.”

Rodriguez, formerly the Council’s Transportation chair, introduced a similar, but unsuccessful, bill in 2015 to daylight the five most dangerous intersections in each borough annually with curb extensions.

Experts agree that daylighting without additional infrastructure is flawed — which is why they demand bulb-outs, bike racks or posts.

“I’ve never been sold on daylighting at corners because the turning radius is larger, hence higher turning speeds,” said Michael King, a former DOT official in charge of traffic calming and now a consultant. “You can mitigate by adding a curb extension, but daylighting in and of itself might not get you what you want.

“Visibility does not necessarily equal safety, as many believe,” he added. “This has roots in the misguided belief that if drivers can see and have time to react, then they will. But they won’t because they are texting, talking, speeding, etc. I would much rather wait behind a parked car that is obstructing the driver’s visibility and slowing her down than stand exposed in a daylit zone.”

So the solution is eliminate the exposure, which has been a key part of Hoboken, New Jersey’s, use of daylighting. The city has not had a traffic death since 2017.

“Whatever it is, you need to physically keep cars from parking there so you don’t have to rely on an army of police or parking enforcement officers to do that work for you,” said Ryan Sharp, Hoboken’s director of transportation and parking.

There’s no public estimate of what it would cost to physically daylight all the remaining dangerous intersections in the city, but it would clearly be in the tens of millions, given the capital construction costs of cement bulb-outs like the one on Henry Street in the above slideshow.

But no price is too high to save lives, advocates and victims say.

“As a mom, I am upset that this corner has had four previous red flag in three years, including someone loosing a leg last year, and I’m sad that apparently someone has to die before a safety evaluation is done,” said Rebecca Van Kessel, an Astoria resident who is friends with Dolma’s father, Tsering Wangdu and is organizing a memorial event for the girl on Sunday.

“He did not seem impressed that they only repainted it,” she added, referring to the grieving dad. “If the city stops short of the maximum effort, we will all be incensed.”