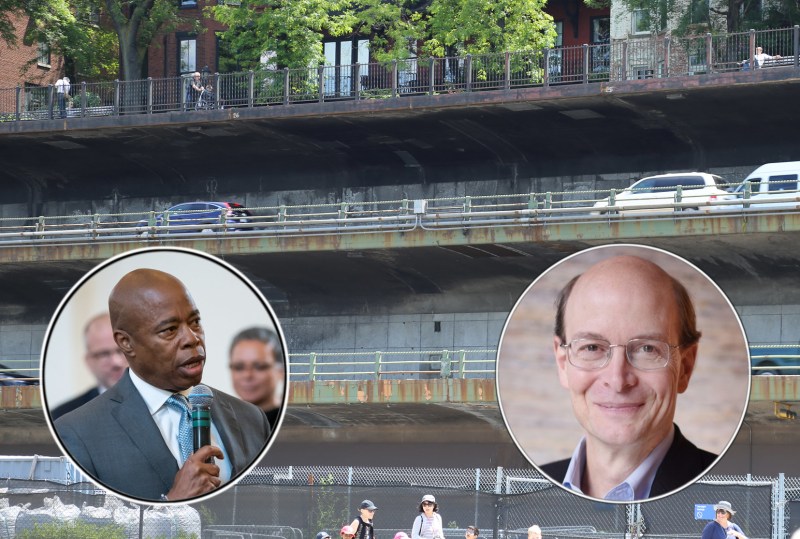

OPINION: Mayor Adams Has Leverage to Force a Reluctant State DOT to Budge on the BQE

City officials admitted this month that their “corridor-wide visioning process” for the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway can only tinker around the highway’s edges without the state Department of Transportation on board. But Mayor Adams and his administration are not powerless against state DOT’s refusal to engage in planning for its own highway — and in fact have real leverage to bring the state to the table.

Adams can do this because, perhaps uniquely among areas of state-city policy, city DOT has two strong levers that make it the equal of state DOT at any bargaining table.

The first stems from U.S. transportation law. For federal money to reach any agency in downstate New York, a regional assembly of agencies known as the NY Metropolitan Transportation Council (NYMTC) must periodically submit a long-range transportation plan, a list of projects for federal aid and modeling output that shows that plans and projects will not worsen air quality.

NYMTC’s long-range plans are much more paperwork than actual planning, but from a legal point of view they are very real to the feds. NYMTC operates by consensus, so a voting member such as the city DOT can delay or veto any of the federally required output. That would suspend the flow of federal transportation aid to the region, including to state DOT and the MTA.

Because of that crisis-inducing effect, vetoing a NYMTC product is kind of a nuclear option, but even saber rattling in that direction gets attention and will likely result in dialogue if not full negotiation over a dispute. The most public exercise of this power I can recall was by Mayor Giuliani in 1997, as part of his push to win greater airport rent payments from the Port Authority.

The second lever is more bilateral between the city and state departments of Transportation and stems from state highway law. Basically, New York City has approval power over state highway projects within the five boroughs. In practice, that manifests as a requirement for the city DOT commissioner to sign engineering drawings for state projects.

When I worked at the city DOT under Mayor Bloomberg and Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan, we used these levers to good effect in a quiet, protracted war over federal bridge funds that lasted roughly from 2010 to 2013. The context was the Great Recession, which left a smoking crater where the state budget once stood. Recently rocked by the disaster of the emergency 2009 closure and subsequent demolition of the Champlain Bridge, thanks to inadequate maintenance, state DOT responded to shortfalls by trying to hog every dime of federal money flowing through its coffers.

During our bridge funding fight with state DOT, engineering drawings for state projects submitted to city DOT were not simply signed and returned, but instead left to idle in a file cabinet — a.k.a., “The Drawer of Power” — to force a conversation between agency leaders. Not having approved drawings for projects scheduled to go to contract is a very real problem for an outfit like state DOT.

Long story short, by exercising the tools available, city government was able to bargain for significant restoration of bridge funds that state DOT attempted to withhold. Though no clear accounting of the issue is available, the totals saved for the city amounted to around $125 million.

A unique leverage goes unused

I’m not holding my breath that the Adams Administration will play this kind of hardball with the state over something as long-range and uncertain as reimagining Brooklyn’s main highway corridor. But beyond the BQE, one could imagine a climate-hawk mayor using these powers to call off destructive state projects like the current work to widen the Van Wyck Expressway and the Belt Parkway.

Fortunately, elected officials, led by Assembly Member Emily Gallagher (D-Greenpoint) and Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso, have caught on to the disconnected New York City outreach process and demanded that state DOT return to the BQE for a more comprehensive look at the corridor.

The BQE has divided North Brooklyn for generations, causing air and noise pollution in dense residential neighborhoods where a major highway does not belong. I asked @NYSDOT about their vision for this harmful infrastructure—and if they're at the table with impacted communities. pic.twitter.com/1M1yQzLp6v

— Emily Gallagher (@EmilyAssembly) February 6, 2023

Until 2011, fixing the cantilever was a state-led project — and it was part of a wider look at the BQE/I-278 in Brooklyn. There is still plenty of material online documenting the significant planning work state DOT put into swapping the elevated expressway viaduct south of Brooklyn Heights for a tunnel, and into finding a way to replace the cantilevered Brooklyn Heights segment that’s now the city’s financial and logistical responsibility.

Out of the blue around Thanksgiving 2011, state DOT under then-Gov. Cuomo walked away from the project. An official notice stated tersely that, “The NYS DOT proposes terminating the Tier 1 EIS for this project.”

Because of this, it’s puzzling that city government has taken on the cantilever project at all instead of forcing state DOT to fulfill its responsibility to maintain Interstate Highway infrastructure. Activists and elected officials engaging with the city DOT’s current process should be asking tough questions about what the city is really up to with regard to the BQE — and why it won’t use its power to push much harder to make a full corridor plan real.

The city’s forthcoming outreach process could be an indirect way to push the state into a new look at the BQE. It could also be a way to dress up a prosaic cantilever rebuild at a time when rhetoric about urban highways has turned toward tear downs and historical redress.

If Mayor Adams and his DOT really want a new end-to-end vision for the BQE, they should clearly say so — and compel the state back to the job using the legal tools at their disposal.

Jon Orcutt was policy director at the city DOT from 2007 to 2014. He is now advocacy director at Bike New York.