DOT Proposes Protected Bike Path, Bus Lane for Washington Bridge (The Other One)

The city wants to repurpose a pair of car lanes on the Washington Bridge uptown for a two-way bike lane and a bus lane next year, giving a dedicated space to cyclists who are currently forced to share extremely narrow paths with pedestrians.

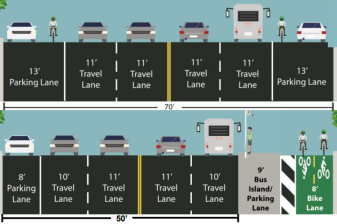

The proposal would take the two outermost of six vehicle lanes on the landmarked 19th-century steel arch over the Harlem River between Washington Heights and the West Bronx, converting the northern, Manhattan-bound lane into a two-way protected bike lane similar what the city did on the Brooklyn and Pulaski bridges, according to a Nov. 2 Department of Transportation presentation.

On the Bronx-bound side, the city wants to paint a dedicated bus lane for the five Metropolitan Transportation Authority bus routes that travel across the span, carrying some 68,000 daily riders.

The two lanes would link to bike and bus infrastructure on either side, benefitting thousands of cyclists and bus riders while also giving back more space to pedestrians on the narrow outer pathways.

Advocates have long called for the city to install better bike infrastructure on the Harlem River crossing. The next connector, the scenic pedestrian and bike High Bridge, closes overnight, making the Washington Bridge — not to be confused with the similarly-named George Washington Bridge over the Hudson River to New Jersey — a crucial passageway between the two boroughs, said one Bronxite.

“It’s huge,” said Lucia Deng, a West Bronx volunteer activist with Transportation Alternative. “The bus lane’s huge as well — assuming it’s enforced.

“It always felt like the Bronx and Upper Manhattan were left behind,” Deng added. “We’re almost always last in line so it’s nice to see them escalate and elevate these issues up here.”

Deng has lived on both sides of the span and frequently makes the journey to Washington Heights to patronize businesses on the 181st Street corridor, but the current setup limits commuters like her to a mere 3.5-4.5 feet path, while motorists get three lanes in each direction.

“It’s just such a horrible experience. It’s loud, you have to squeeze by one another,” she said. “People are on there at all hours, it’s used a lot… I’ve seen someone literally carry a washing machine across.”

It didn’t used to be this way.

The bridge opened in 1889 as the next major river crossing after the Brooklyn Bridge opened six years earlier, and it was “one of the nation’s finest 19th-century steel arch bridges,” the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission wrote in 1982.

The Interborough Railroad Company began operating two streetcar tracks over the bridge in 1906, the same year the first automobiles began using the crossing. Officials narrowed the sidewalks and widened the roadway in the 20th century amid more car traffic, according to the LPC, especially following the Robert Moses-era highway constructions of the Harlem River Drive and the Cross-Bronx Expressway.

At long last, the city will give back some of that space to non-drivers.

The span’s upgrades fill in the missing link between the 181st Street busway in Manhattan and the University Avenue bus lanes in the Bronx and speed up commutes as long as drivers don’t block it.

The Amsterdam Avenue bike lanes, which end a few blocks north of the bridge in Manhattan, and the Edward L. Grant bike paths in the Boogie Down would also be better connected via the bridge.

“When you don’t treat the bridge, then all the rest, the benefits are significantly reduced,” said Deng. “The connector was the piece that was missing.”

The bike lane would reconnect to the wider footpath on the Manhattan side and continue on through McNally Plaza and to a proposed protected path through Laurel Hill Terrace to Amsterdam Avenue. To make space for that, DOT will remove 20 parking spaces on Laurel Hill Terrace.

On the Bronx side, the bike lane is set to continue on the roadway of one of the entrance ramps, taking one of two lanes.

At a presentation to Manhattan Community Board 12’s Traffic and Transportation committee Monday, members of the civic panel lamented the loss of parking on the Manhattan side, but a DOT planner said that was needed to keep a continuously-protected lane for cyclists.

“We try to maintain the protected connections as much as possible. They really only work if they’re continuous,” said Patrick Kennedy. “For us we felt that was the best option, the safest option.”

The committee ended up giving a unanimous, albeit advisory, vote in favor of the project.

An overwhelming majority of locals don’t use a car to get around. In Highbridge and Morris Heights, 62 percent of residents live in a car-free household, 67 percent use public transit to get to work, and only 20 percent drive for their commute. On the Manhattan side, 70 percent of Washington Heights locals live in car-free households, 69 percent commute by public transit and only 12 percent by car, according to DOT.

Drivers frequently take the bridge as a detour for the Cross-Bronx Expressway on the Interstate 95 corridor, traffic that could just as well use the Alexander Hamilton Bridge. But those driver are already accustomed to the bridge losing one lane in each direction periodically due to an ongoing construction project.

Kennedy told the community board that DOT plans to install the changes next spring and wrap it up by the end of the summer or early fall of 2023, about the amount of time it took officials to set up the Brooklyn Bridge bike lane last year.

“I envision something similar to that taking place here,” said Kennedy. “I would say it would take a number of months to do, so probably starting sometime in the spring, hopefully ending sometime in the late summer early fall.”