EXCLUSIVE: Reckless Driver Who Killed Baby Apolline Took Driver ‘Accountability’ Course — But It Didn’t Change a Thing

Such "safe-driving" courses are seen by some as a model for changing the behavior of reckless drivers. But there is limited evidence they work — and certainly did not in the case of Tyrik Mott

EXCLUSIVE | The recidivist reckless driver who killed a 3-month-old baby at a Brooklyn intersection last month had completed a version of the safe-driving course that advocates hope will keep the worst offenders off the road, yet he did not alter his violent driving behavior in any way — the latest reminder of the shortcomings of existing efforts to reform the worst drivers or keep them off the roads entirely.

Tyrik Mott, who cops said killed Apolline Mong-Guillemin in a crash in Clinton Hill on Sept. 11 after racking up close to 100 red-light and speed-camera tickets since 2017, had completed the so-called Driver Accountability Program — a 90-minute session run by the Brooklyn Justice Initiative and Center for Court Innovation that features emotional testimonies from families who have lost loved ones to traffic violence. With its focus on empowering individual change, the course also requires participants to identify their own poor driving behavior, and how they plan to reform it.

Mott’s completion of the course was recorded on May 4 — yet from that day until Sept. 11, he accrued 26 more school-zone speed camera and red-light tickets. He had, in fact, gotten a camera-issued speeding ticket on May 4, the very day his course participation was logged. And he got a speeding ticket in the Bronx the day before cops say he fatally struck Baby Apolline at Gates and Vanderbilt avenues.

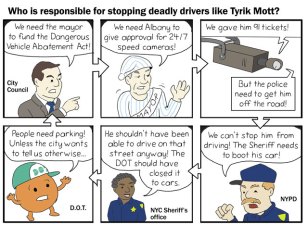

Mott’s failure to remain out of trouble after taking a court-mandated safe-driving course raises red flags as the de Blasio administration belatedly implements the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program, which will require a similar course for drivers who get 15 or more camera-issued speeding tickets or five red-light tickets in any 12-month period. Mayor de Blasio has been under fire since the death of Baby Apolline to explain why his administration failed to get Mott, 28, off the road even though he had racked up 108 camera-issued moving violations and thousands of dollars in unpaid parking tickets since 2017 — more than enough to subject him to towing or booting that never occurred.

What went wrong?

Mott was stopped by cops on Feb. 3, 2021 for a broken headlight and was later arrested for driving with a license that had been suspended because he failed to pay many of the 75 tickets for speeding in school zones and going through red lights, plus the 43 parking tickets, that he had racked up since June 30, 2017, records show. (He had already gotten nine speeding tickets in 2021 before that encounter with cops on Feb. 3.)

After a hearing on the charges, Brooklyn Criminal Court Judge Keisha Espinal did not bar Mott from driving, nor was his vehicle impounded, despite having far more than the threshold of unpaid tickets plus multiple prior suspended licenses. He continued to drive — and, in fact, got 11 more camera-issued moving violations between Feb. 3 and May 4. But the only matter on the table before Judge Espinal were the current charges: the license suspension and the broken headlight, according to a law enforcement source.

Espinal’s inability to get Mott off the road is no outlier. In 2018, Mott was slapped with a violation for cutting someone off without signaling, and almost hitting a cop, at Atlantic and Pennsylvania avenues. He was fined, though it’s unclear how much or whether he paid. At the time of that arrest, Mott’s car had already racked up six speed-camera tickets and three red-light tickets between June 30, 2017 and Dec. 22, 2017.

Instead of preventing him from driving, Espinal — with the support of the Brooklyn DA and Mott’s lawyer — released Mott on the condition that he complete the safe-driving course. Then, with fresh proof that Mott did indeed take the then-virtual course, Espinal on May 14 dismissed Mott’s case with an ACD — an adjournment in contemplation of dismissal — a legal maneuver that allows a guilty person’s record to be cleared if he or she stays out of trouble for six months.

As has been widely documented, Mott did not stay out of trouble, racking up the 26 additional camera violations between May 4 and Sept. 11 — the day he killed Baby Apolline, cops say.

The failure of authorities to get him off the road has many fathers. But a key method of ensnaring reckless drivers — revoking their licenses — remains frustratingly elusive because camera-issued tickets do not count as points against a driver’s record, even though just three camera-issued speeding tickets are equivalent to enough points to earn a driver a license suspension, according to state DMV rules. Only police-issued tickets count against a driver’s record — and police have been issuing fewer and fewer of them, city statistics show.

A course is a course (of course, of course)

The course Mott took was part of a program at the Red Hook Community Justice Center launched in 2015 under then-Brooklyn District Attorney Ken Thompson as part of a collaborative effort among the NYPD, Center for Court Innovation, Transportation Alternatives, Families for Safe Streets, and Council Member Brad Lander — and it is similar to the program that will be scaled up throughout the city under a 2018 Lander bill that created the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program. The city had been negotiating with the Center for Court Innovation to run courses citywide, but the city severed its ties with the group earlier this month for reasons that remain unclear. For now, at least, the Department of Transportation will create the courses in-house and begin the program by November, as Streetsblog has reported. The DOT has said it had unspecified “issues” with the Center for Court Innovation. (The group declined to comment on its negotiations with the city.)

Since its launch, more than 2,500 people have gone through the Driver Accountability Program, which currently only serves drivers convicted of driving offenses such as speeding or recklessness, according to the program’s project director Amanda Berman.

In exchange for completing the program, the District Attorney agrees to either reduce or forgive fines, as in Mott’s case. The goal is to change behavior and reduce recidivism through a course, not a cell, according to Berman.

But beyond the obvious failure of Tyrik Mott to change his behavior, it’s unclear how successful the existing program is. Berman says preliminary data shows that participants who completed the program were 40 percent less likely to be rearrested for traffic-related offenses than drivers who had also been arrested for similar traffic-related offenses but did not go through the program, and that 89 percent of respondents reported a change in their driving behaviors after completing the program.

But that 89 percent figure represents self-reporting; if there are actual changes in driving behavior, no one knows. Course participants are not tracked (though Lander’s bill does require the city to monitor and report back to the Council how many people completed the course — and how many continued to receive camera-issued tickets; such monitoring is simply not happening now).

Streetsblog repeatedly asked the Center for Court Innovation for more details of the course, but none was provided. Chalfen declined to discuss Mott’s virtual participation in the course beyond confirming that he completed it. Neither Chalfen nor the Center for Court Innovation would discuss how participants’ engagement is tracked.

“Because he completed the program, [his February case] is set to be dismissed in November,” said Chalfen. It’s possible, though not certain, that the dismissal will be revoked in November due to Mott’s new arrest for manslaughter for the Sept. 11 killing Baby Apolline. Mott, who did not have a valid license at the time, initially fled on foot, police said, but was later arrested. Mott’s lawyer, Lance Lazzaro, told Streetsblog that he made bail late last month after spending several days and nights in Rikers, but a friend or relative who answered the door at Mott’s Crown Heights home last week declined to speak with Streetsblog. Mott is next due in court on Oct. 14, records show.

With or without a course, the number of people who get a second camera-issued speeding ticket generally plummets, according to DOT. Speeding at fixed-camera locations dropped 71.5 percent after the city completed the installation of at least one camera in all 750 school zones by June, 2020, and injuries dropped by 16.9 percent. And two-thirds of vehicles that received a speed camera violation in 2019 did not receive another within the calendar year, according to DOT.

The 40-percent success rate touted by Berman can be seen another way: it means that the course does not have a lasting impact on 60 percent of the people who complete it. Lander said he knew that the course would not provide a fix-all approach. It’s just one piece of a street safety puzzle that must include better design and some NYPD enforcement.

“I think there will be good evidence that the course will lead to meaningful behavior change for some people. It’s not as rigorous as what we need. A 40-percent drop in recidivism is good, but then, by itself, clearly that would leave 60 percent of people for whom the course did not lead them to change their behavior,” he said. “We never tried to hold out DVAP as a comprehensive panacea, but more like one important step forward.”

A small step. The Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program does not account for how to deal with drivers who are forced into the program, but then do not reform their reckless driving, though Lander says the law could later be scaled-up — at a later date — to include new sanctions such as automatic vehicle under some circumstances. And a spokesperson for DOT said that a driver forced to take the course because of flagrant disregard for the law could be sent back to class if there are additional infractions — though the agency declined to specify how many infractions would trigger a re-do.

And the fact remains: program specifics, including how long the courses will be and what they will consist of, have not yet been worked out, according to DOT and Lander.

“The plan is to get it up and running first, and start to learn the impact,” said Lander, who concedes that the city needs “a more comprehensive framework for combating repeat reckless driving.”

“I don’t think [Mott’s recklessness after taking the course] tells us it is unnecessary; it tells us that we need to get a good deal more thoughtful and sophisticated than we are.”

And while the program is still weeks away from starting, so far at least 2,000 drivers have already met the threshold for requiring the safety course, having been caught by city speed cameras 15 times or on red-light cameras five times in any 12-month period, Streetsblog has reported.

Activists agree that the flaws in the DVAP program show the folly in hoping that one program alone can rein in reckless drivers when generations of city, state and federal leadership has failed to do so. So in addition to the program, the city must similarly work to reclaim the roads from cars, and give streets back to the people.

“Driver accountability programs are effective tools to make streets safe and reduce repeat offenses by reckless drivers,” said Marco Conner DiAquoi of Transportation Alternatives. “But, Vision Zero has always required a safe systems approach. No one policy prevents every crash. This case shows a need for greater accountability – including potential vehicle seizure – if driver behavior does not change. But we still believe that a significant expansion of street redesigns are the best way to slow down drivers and prevent traffic violence.”

The mother of 12-year-old Sammy Cohen Eckstein, who was killed by a reckless driver in 2013, agreed, saying that repeat offenders like Mott must immediately be stopped from getting back behind the wheel.