The mandatory parking minimum law is the demon child of car culture and NIMBYism — but it is finally being attacked by progressive leaders.

The city must do away with an antiquated zoning rule that forces developers to include parking spaces in many new developments across the city — a requirement that leads to more congestion, more pollution, less affordable housing and higher construction costs that are passed along to tenants, experts say.

At a moment when scientists say human activity has caused unequivocal harm to the planet and is speeding up climate change faster than previously anticipated, the time has come to pluck the lowest-hanging fruit: eliminating part of the zoning code that requires developers to include parking spaces in new projects.

“Parking minimums lock us into auto-dependency [and] the climate crisis demands we move to greener transportation methods,” said Will Thomas, the executive director of the pro-housing organization Open New York. “Abolishing parking minimums at this time seems like a no-brainer.”

First, a little history lesson

The first parking minimums were written into the city’s zoning laws for residential buildings in 1950; and the rules were amended in 1961 to include commercial and mixed-use buildings. The exact number of off-street parking spaces currently mandated for new developments is determined based on the use of the building, and the zoning district in which it sits.

At the time those laws were created, according to a Department of City Planning spokesman, elected officials believed that requiring off-street parking would limit congestion on the street. They were wrong.

In the decades since, the requirements have been relaxed; in 1982, all parking minimums were eliminated in Manhattan below 96th Street on the East Side and below 110th Street on the West Side (in response to the 1970 Clean Air Act); they were later reduced in Downtown Brooklyn and parts of Long Island City; and in 2016, the city’s Zoning for Quality and Affordability plan eliminated parking minimums for fully affordable housing developments in transit-rich areas; and as part of neighborhood-wide rezoning plans such Inwood, the city also lowered or eliminated parking minimums for all new developments.

Minimum parking requirements are unaffordable housing requirements.

Here are 37 studies showing how the cost of parking gets passed on to tenants in the form of higher rents.

(THREAD) pic.twitter.com/4LMm7OBwK1

— Aaron Carr (@aaronAcarr) July 29, 2021

A wholesale elimination of parking minimums across the city would require a lengthy review process involving all 59 community boards and the five borough presidents, then a vote from the city council. It would also require an extensive environmental review of the effects of such a change, according to a Department of City Planning spokesperson.

For now, that means the city is relying on individual developers to carry out car-reduction strategies out of the goodness of their own hearts, basically. Consider transit-rich Downtown Brooklyn, where the real-estate firm Alloy Development had to jump through hoops to get permission to nix the parking requirements for its planned mega-project — dubbed the Alloy Block (formerly known as 80 Flatbush) — at the junction of Flatbush Avenue, Schermerhorn Street, Third Avenue and State Street.

Under existing zoning laws, Alloy was required to include 200 parking spaces, which the builders hoped to not provide, citing the worsening climate crisis, existing congestion in the area, and the building’s proximity to transit. The developers eventually won the right to include no parking, but it was a long, expensive, and difficult process, according to Alloy CEO Jared Della Valle.

“We are living through a climate emergency and need to start acting like it,” said Della Valle. “The city should be actively discouraging car use, not mandating it — especially in its most transit-rich neighborhoods. As an additional step, we think the city should eliminate parking minimums citywide.”

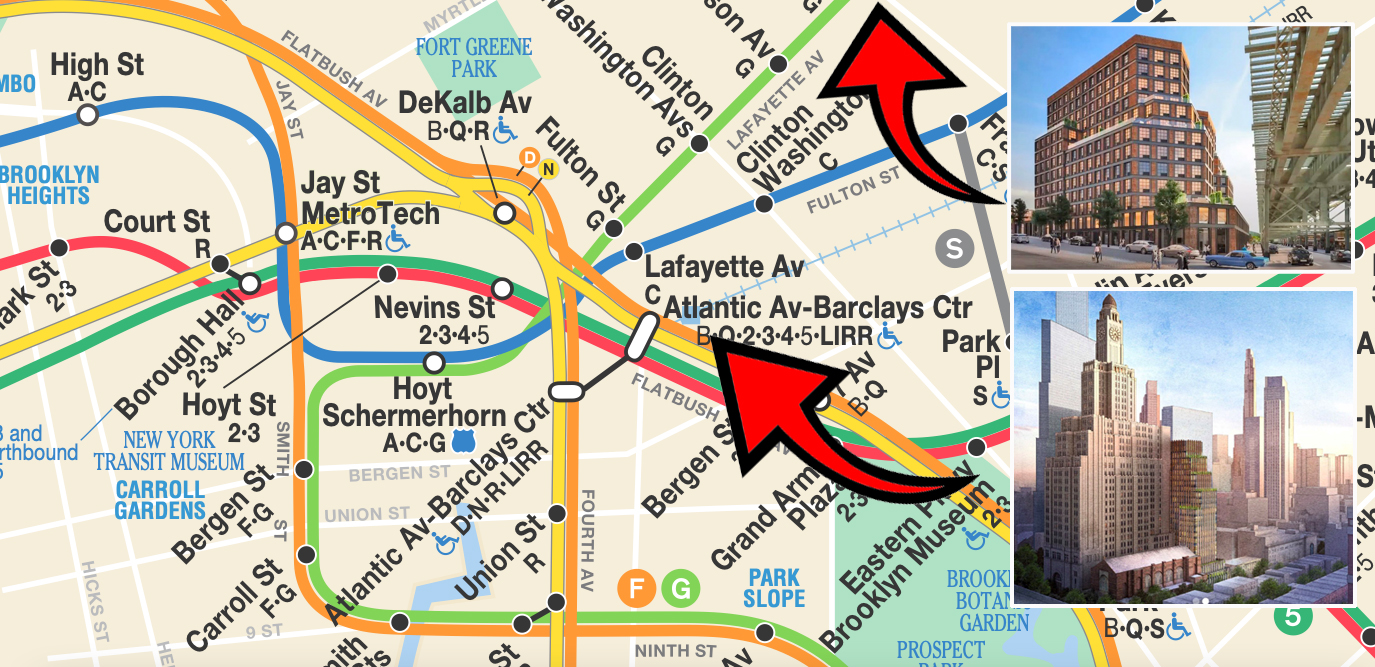

And not far from Alloy’s planned mega tower, developers Gotham Organization are similarly in the process of seeking city approval to build a 23-story mixed-use tower at 130 St. Felix St., which is at the nexus of 11 subway lines, the Long Island Rail Road, at least a dozen bus stops, and many Citi Bike racks.

Nonetheless, under current zoning, Gotham Organization is required to include at least 17 off-street parking spaces, which is 20 percent of the total number of market-rate units planned, according to the Department of City Planning.

The site is located in the middle of just about every subway line in Brooklyn. Besides the subway, there are a plethora of options for residents to commute for work, play, school and care such as citibike and buses, and of course walking. pic.twitter.com/qxzvny2JVh

— passenger princess (bus edition) (@nicoleamurray) May 10, 2021

Gotham is seeking a rezoning for its development through the Uniformed Land Use Review Procedure — and if they get the waiver on the parking requirement, they can include affordable housing and an expansion of the adjoining Brooklyn Music School.

But Brooklyn’s Community Board 2 rejected the request in May as part of its role in ULURP — the latest evidence that local community boards, which are often stacked with older, whiter, and disproportionately wealthier residents unrepresentative of the entire community — are out of step with our current needs, advocates said.

“Residents will be better served with the addition of affordable units than with parking for people who can afford to live here without a subsidy,” said Nicole Murray, a member of the Ecosocialist Working Group of NYC-Democratic Socialists of America.

Something else that shouldn't be up to a community board is waiving parking minimums. If someone building at 130 Felix St. doesn't want to include parking, don't make them include parking.

Here's where 130 Felix is. The red circles I drew were at random oh wait that's not true. https://t.co/jacQRri6ng pic.twitter.com/UAXQU0tRoc

— Second Ave. Sagas (@2AvSagas) May 21, 2021

And over in Woodside, Queens, developers seeking a rezoning in order to build a 13-story tower with affordable housing at 62-04 Roosevelt must include a minimum of 156 parking spaces because of the existing parking minimum requirement, despite the fact that the structure would nearly sit on top of the 61st Street station of the 7 train. Without a rezoning, the developers could only erect a nine-story building with no affordable housing and 148 parking spaces.

The real-estate team, Woodside 63 LLC, even acknowledged during a community board meeting back in June that the development’s proximity to transit makes it an ideal location for more affordable housing and less mandatory parking.

“We love the fact that it has proximity to two major transit lines. It’s a transit-oriented development,” said Stephen Lysohir, president of the EJ Stevens Group during a June 2 meeting. “With all the talk about less vehicles, reducing pollution, urban planners love sites like this.”

Still, unlike the developers behind the 130 St. Felix St. project, Lysohir and his team have not applied for a waiver to nix parking, according to a project spokesman, adding that the developer might mitigate the damage of all the required parking spaces by not necessarily using them in the traditional manner. The development also requires 116 bike parking spaces, according to a city planning spokesperson.

“The rezoning process started years ago and opinions were very mixed about parking needs,” said Jordan Press. “We’re mitigating concerns by being very proactive in supporting bike usage, car sharing and electric vehicle charging.”

Some advocates and community board members say they still support the rezoning in order to bring more affordable housing to the community — since the alternative would be only eight fewer spaces and no below-market-rate housing — though ideally the city would do away with its parking requirements entirely so as not to force communities and developers to choose between the two, one of which only further burdens a neighborhood.

“Having 156 cars just causes more congestion on adjacent streets, whether they’re looking for parking or not,” said Laura Shepard. “The city should absolutely abolish parking minimums everywhere.”

I'm mad at myself for not trying harder to kill the 156 parking spots in the 62-04 Roosevelt rezoning. It's 2021 and @NYCPlanning still requires them even though this is an incredibly walkable and transit-accessible spot! @QnsBPRichards @JimmyVanBramer https://t.co/2l2hrcYugr

— Laura Shepard (@LAShepard221) August 13, 2021

And back in Brooklyn, a neighborhood rezoning in Gowanus would reduce parking minimums for new developments there from the now-required 50 percent of market-rate units to 20 percent.

As expected, some residents fumed over the loss of precious parking spots. But Council Member Brad Lander, who represents the area, and who will take office as the city’s comptroller next year, said he is supportive of the push to reduce parking minimums, so long as it goes along with vast improvements to public transportation and expanding the bike network.

“Citywide, as we move forward and are thinking about the work we need to do to move away from gas-powered vehicles for our city, for reduction in driving in general, yes I think we should move away from minimum parking requirements,” said Lander. “I don’t think it’s a panacea on its own, it’s one important step to a broader transportation transformation.”

In case anyone was wondering what the Gowanus rezoning opposition is up to today… pic.twitter.com/o8MDpCW6PS

— Annie Weinstock (@Annie_Weinstock) June 1, 2021

Forcing developers to require parking often means higher construction costs through excavation work and additional square footage that then gets passed onto the residents, even if they don’t own a car — and more than half don’t.

A former president of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, and now head of Brooklyn-based real estate development firm Totem, told Streetsblog that the added cost of including parking could instead go towards providing space that benefits everyone.

“Most people put parking underground, it costs money to excavate to put parking there. That money can be spent on other things: more affordable housing, more community space,” said Tucker Reed, though he added that he doesn’t believe it’s “a one-size fits all approach.”

“With the effects of climate change and demand for addressing the crisis from a policy perspective, the city is looking at opportunities to reduce that requirement wherever they can and certainly abundance in subway access,” said Reed.

Can New York’s car culture be tamed?

Mandatory parking minimums are the demon offspring of car culture and NIMBYism — but they are being attacked more and more by progressive leaders.

For example, months ago, during a mayoral forum, several candidates were asked a simple yes or no question: “Do you support eliminating minimums parking requirements from the zoning code?” Progressive candidates Comptroller Scott Stringer, Dianne Morales, and Art Chang all said yes. Only former Department of Sanitation Commissioner Kathryn Garcia — who was not running as a progressive — said no. (Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams was not at the forum, and the presumptive next mayor did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story; he does support the Gowanus rezoning, but he has not weighed in specifically on the parking issue).

The fact that such a question is now being asked — and that some of the race’s leading progressive candidates said they would support it — means it’s time to reconsider the policy, according to Rachel Weinberger, a fellow at the Regional Plan Association, who wrote a 2008 report on how guaranteeing parking would guarantee driving, and more pollution.

“As recently as 10 years ago, there was some sentiment that requiring parking was sort of a necessary lubricant to getting neighborhoods to accept new development,” she said. “Even having that conversation suggests more light around a lot of fear and that it’s mainstream enough for a mayoral debate. Is it possible to happen in New York? Yes, we’re moving closer and closer to it every year. It’s good policy and beginning to infiltrate the mainstream debate.”

Other cities have already set such a precedent — Buffalo did away with its parking requirements in 2017, San Francisco in 2018, and most recently Minneapolis this past May, the results of which so far have not been catastrophic, said Weinberger.

And specifically in Buffalo, a recent study revealed that 47 percent of developers of major new buildings chose not to build parking, given the option. The suggests that “earlier minimum parking requirements may have been excessive,” the study concluded.

“We’ve certainly seen a lot of evolution, because there have been an increasing number of examples of parking minimums — at least mitigated, if not eliminated — that have not spelled the death of development and cities,” said Weinberger. “Recent evidence from Buffalo shows that eliminating parking requirements has actually facilitated development … proving parking is dead weight on the development.”