OPINION: To Ban Cars, Socialize Them

The city could repurpose its huge fleet into a car-share one, starting with the NYPD's huge cache of vehicles.

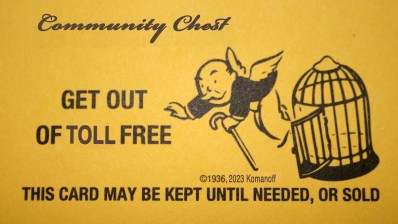

Pedestrianization, congestion pricing, dedicated bus and bike lanes, parking maximums, and transit-oriented development dominate the headlines when it comes to reducing the number of cars in cities. Presumptive mayor Eric Adams even tweeted on Saturday in support of congestion pricing. But there is one unsung tactic that reduces the number of cars on the road and their consequences without big public investment, redevelopment, or a toll on central-business-district-bound drivers: expanding car access through car share.

By “car share,” I do not mean ride hails (taxis, Uber/Lyft). Car share is the actual sharing of a vehicle among several people. Arrangements can entail formal corporate rentals from car lots (Hertz, Zipcar), point-to-point sharing in which cars can be picked up and dropped off anywhere in a defined zone (Car2Go), peer-to-peer sharing in which members can rent out their cars (Turo, Getaround), and informal arrangements such as sharing among housemates and carpooling.

To reduce (or even ban) private cars in the city, we should socialize them.

The Department of Transportation quietly expanded and made permanent its program to provide street and municipal-lot parking spaces for car-share services in April. Still more needs to be done to expand opportunities. Parking spaces in co-ops could be upgraded to electric connections for car-share companies, as was done at the Seward Park Co-op in Manhattan.

The city could go further and municipalize its own fleet into a car-share one, perhaps starting by repurposing the NYPD’s huge cache of 9,000 SUVs, sedans, and smart cars. A public fleet could obviate the confusing parking rules and regulations (part of Car2Go’s unfortunate downfall), provide unionized jobs and training for care and maintenance, and would not be beholden to shareholder dividends. All revenue from membership could be funneled back into the system and subsidize less-profitable areas in which residents may need car share the most.

Car-share services discourage individual car ownership. The U.S. Department of Transportation reported in 2016 that “the most current studies and member survey results released by U.S. and Canadian car-sharing organizations show that up to 32 percent of car-sharing members sold their personal vehicles, and between 25 percent and 71 percent of members avoided an auto purchase because of car-sharing.” A 2008 online survey by Access Magazine of 6,281 members of car-share services across the country showed a whopping 49 percent reduction in personal car ownership among them, mostly of one-car households becoming no-car households. (A smaller change occurred with two-car households becoming one-car households.) These findings mean that there is a latent desire to shed the burdens of personal car ownership so long as access can be assured.

These arrangements work because ownership of a car is not the same as unrestricted access to one, and in fact can be a barrier to access: crushing maintenance costs; predatory subprime loans and skyrocketing insurance rates; damage or theft because of lack of safe storage or driving conditions; and of course, fuel costs, not just on personal wallets but on the planet for the massive oil infrastructure needed to support this country’s about 90 percent personal car-ownership rate. Individualizing ownership means individualizing these costs and risks, especially on those most vulnerable economically.

A reduction in private cars on the road necessarily means a reduction in the negative consequences of their use. The DOT said that its tiny, three-year pilot led to a 38.7-million-mile reduction in annual vehicles miles traveled in the city—no small beer. The Shared Use Mobility Center estimates that if just 10 percent of all households were enrolled in a car-share program, the San Francisco Bay Area could see a reduction of 50,000 personal vehicles, 267 million fewer miles traveled annually, and 109,000 metric tons of CO2 saved from the air. Even sprawling Atlanta could see reductions of 3,000 cars, 13 million miles, and 5,000 metric tons of CO2 annually. Even more exciting are findings that car-share members are more likely to use public transportation and walk or cycle—great news for transit agencies and for public health.

To expand further the benefits and reach of car share in the city and beyond, New York also must amend its insurance regulations that stifle car share. Under current law, a car owner’s personal insurance policy provides coverage to anyone who drives the vehicle with the owner’s permission, but not when the driver rents the car for a fee. In 2013, Gov. Cuomo’s administration fined Turo (formerly RelayRides) $200,000 for telling users they would not be personally liable for renting out their car. Seven years later, Turo is back, but only as a commercial service. Individuals in independently organized groups should be able to create membership, fee-based car-share services in their own communities without risk of losing their insurance.

The sharing economy in cars, like in so much else, is the future.

Nicole A. Murray (@nicoleamurray) is a member of the Ecosocialist Working Group of NYC-Democratic Socialists of America.