Andrew Yang Says Community Boards are ‘Positive For Democracy’ — Even When Reminded That They’re Not

Andrew Yang thinks community boards are a bastion of democracy — even if they end up obstructing his agenda as mayor.

At a Battery Park press conference on Tuesday announcing his plans for “democracy reform” — which include lowering the municipal voting age to 16 and granting non-citizens the right to vote — Streetsblog asked Yang how community boards fit into his vision. Are these groups of citizens — who are appointed by borough presidents and local council members — more likely to be conduits of popular democracy or do they have too much influence over city governance?

“What an interesting question. I feel like community boards are tremendous because it’s people stepping up in their neighborhoods trying to address and resolve issues that matter to them and their neighbors,” the candidate replied. “I have a very hard time imagining how you could see community boards as anything but positive for democracy, because it’s a very high level of civic engagement.”

Reminded that community boards often impede life-saving bike lanes and traffic calming infrastructure, Yang insisted he had no issue with them.

“It’s interesting. Again, I appreciate the people that want to give a voice to interests in their communities. I just see that as something to be admired,” Yang said.

Community boards have no actual authority to make laws or veto city projects — their volunteer roles are purely advisory. Yet over the years, city government, especially the Department of Transportation, has given community boards an outsized amount of influence that is mostly used to discourage the administration from carrying out road redesigns that can make the city safer.

Members of community boards have delayed street calming measures and crucial bike infrastructure across the city — in many cases for years, costing lives. Their members have stoked a racist police crackdown on delivery cyclists, advocated for tow pounds over affordable housing, suggested that some pedestrians deserve to die, and that low-income workers don’t have a right to relieve themselves with dignity. They have opposed popular programs like open streets and the installation of Citi Bike racks, and demand the right to break traffic laws when the laws don’t suit them.

One community board even used city money to buy itself a fancy car.

Mostly, their objections to changing the lived environment boils down to complaints over a loss of parking spaces, a position that is out of step with a city that largely does not own cars, and would prefer to see valuable curbside real estate used for something else. Sometimes, members of community boards complain about a lack of “engagement” by the DOT.

Just told @bdhowald that the monthly Manhattan CB8 transportation committee meeting has been shockingly tame so far, right before one board member went on an about 5 minute rant about how outdoor dining is a blight on the community

— Julianne Cuba (@Julcuba) May 5, 2021

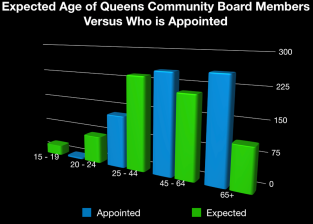

In 2018, New Yorkers voted to amend the city charter to limit the service of community board members to four consecutive two-year terms. The amendment also stated that borough presidents must turn over demographic information on the city’s 59 community boards to ensure that they actually represent their neighborhoods, but so far that data has been spotty.

Yang clearly hasn’t acquainted himself with the lengthy, paint-peeling community board process (sometimes there are fisticuffs and Epstein allegations!) since he was asked about “community” opposition to bike infrastructure at the Bike NY forum in March.

Other candidates weren’t much better. The New York Times-endorsed Kathryn Garcia said she would keep the boards’ advisory role, but wouldn’t let them stop the DOT’s bike network. Shaun Donovan said something about introducing improvements as part of a “comprehensive set of options.” Ray McGuire had his bicycle in the frame behind him.

Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, who is virtually running neck-and-neck with Yang in the recent polls that still show “undecided” dominating, said he would use “credible messengers” to dispel the notion that bike lanes are akin to gentrification. But he also said this: “I’ve communicated with community board members around the borough, and I’m telling you that at the heart of their concerns, they feel, ‘Eric, no one is talking to us; they’re talking at us.’”

Scott Stringer had a somewhat valiant, if unrealistic plan for addressing community boards: “I will commit to this: As mayor, I’ll go to community boards. I’ll build consensus around the table.”

Odds and ends

While Yang was in front of the Statue of Liberty to ostensibly talk about his democracy reforms, he also took the opportunity to hype a recent New York Times story that detailed how Adams reaped campaign donations from firms with business before the city, and then multiplied those donations under the city’s matching funds program.

“Seeing another candidate violate these rules and then dismiss it as a paperwork issue is extraordinarily upsetting,” Yang told reporters, adding that he had filed a complaint with the city’s Campaign Finance Board. “New York: Eric Adams took your tax dollars and used them to amplify special interests here in New York City that did not need it.”

Streetsblog asked Yang if he too could be accused of “amplifying special interests” since his top campaign adviser was a longtime lobbyist in New York for clients like the Police Benevolent Association and Uber. The lobbyist, Bradley Tusk, literally referred to Yang as an “empty vessel,” which we pointed out to the candidate.

“I think there’s a major, major distinction between people who work on your campaign who may have lobbied at some point, which I think is true with just about every campaign, and violating campaign finance rules in front of all of us,” Yang replied.

Adams’s campaign responded to Yang’s critique with its own letter to the CFB, alleging “self-dealing” between Yang’s mayoral campaign, his nonprofit, and his presidential campaign.

“Andrew Yang literally paid himself from his own campaign to run for office and had his campaign buy more than $225,000 worth of copies of his book,” Adams’s campaign spokesperson Evan Thies said in a statement. “He’s funneled more than $1 million from his dark money nonprofit to his two campaigns, loaned his bankrupt presidential campaign hundreds of thousands of dollars, and left a trail of highly questionable activity between multiple entities that promote him. If anyone deserves to be investigated, it’s Andrew Yang.”