Bronx High School Students Help DOT Calm Streets in Dangerous Morrisania

And the children shall save them.

A group of Bronx high school students — fed up with the number of crashes in a section of Morrisania filled with schools — created a safety plan with the Department of Transportation as part of an after-school program. And the plan is expected to be implemented later this year.

The proposal [PDF] would narrow some roadways, add protected bike lanes, reduce crossing distances and generally calm traffic in a rectangular zone roughly bordered by East 161st Street, Trinity Avenue, East 166th Street and Prospect Avenue. It includes two large housing projects and contains or nearly contains 16 school buildings housing two dozen learning centers.

Most important, between 2014 and 2018, there were 201 total injuries in car crashes, with roughly 30 percent of the victims cyclists or pedestrians, often kids. And of the nine severe injuries during the period, six were to cyclists and pedestrians, according to DOT data.

“This is a unique location with lots of schools,” said the agency’s Bronx Commissioner Nivardo Lopez. “It cried out for safety.”

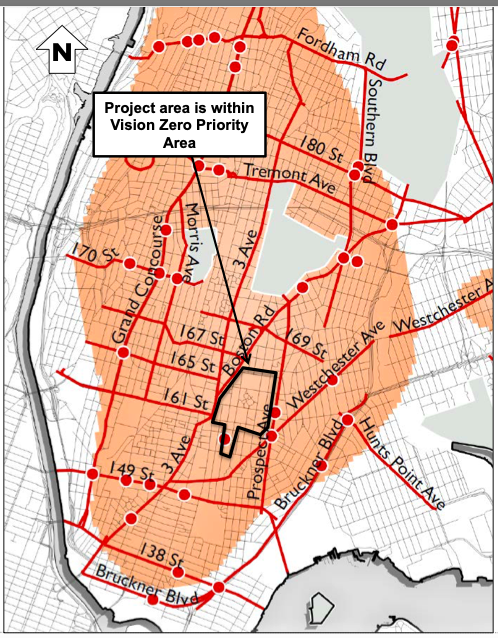

Children and their parents have been bellowing for years, but it wasn’t until 2019 that the city made the immediate area, plus scores of surrounding blocks, a Vision Zero priority zone (see photo).

That’s when the DOT’s school safety unit reached out to the I Challenge Myself after-school program to get kids involved in the project of making their own roadways safer. About a dozen students participated.

“We came in trying to make streets more safer and lessen the amount of accidents in those areas,” said Izedeen Musa, a 15-year-old sophomore at University Heights HS, citing one corner (East 163rd Street and Triton Avenue) that had 38 crashes in four years.

“That’s just one corner,” he added. “So we went out into the field with the DOT and saw the problem: most of those streets are so wide. We knew that if we narrow the road, it will be easier to cross, you can see the cars better, and the cars will slow down.”

Musa recalled one of the pre-pandemic days in fall, 2019 when he and his schoolmates got to use DOT radar guns to track speeders.

“We saw lots of cars speeding,” Musa said. “But once they saw us in their vests, they slowed down.” (Point of information: there are not enough DOT workers in reflective vests to deploy them along every city corridor.)

Jeffrey McDuffie, a project manager in the DOT’s small school safety office, said he was amazed how intuitively the students “got it.”

“They were able to take random treatments from our toolkit and know what to do with them,” he said. “We were thinking thinking they wouldn’t know where to place bike lanes or painted islands, but they did. And they threw in some concrete islands, too.”

It’s not the first time that the DOT has worked with school students, of course, but most of the work involves education, not engineering. But Lopez said the agency benefits from the perspective of non-drivers.

“Young students are very attuned to the rhythm of the street and the danger pedestrians face,” he said. “They are very willing to come up with solutions and ideas to slow down vehicles.”

It’s a perspective that could certainly inform how the Department of Education protects its students as they make their way to and from school buildings — but the agency has consistently rejected pressuring the city for car-free streets near schools, as Streetsblog has reported.

Here’s how The Bronx project breaks down:

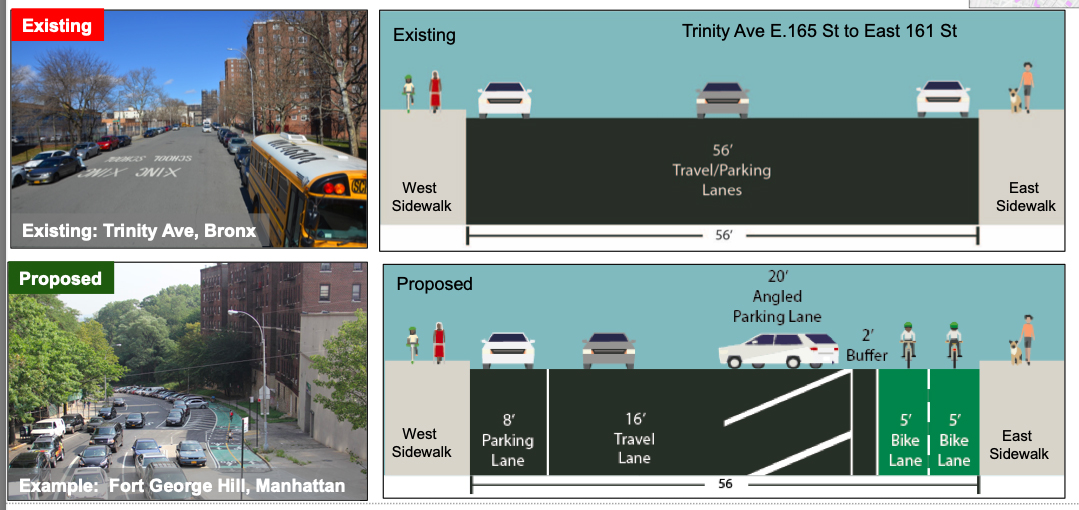

- Trinity Avenue from E 166th to E 161st streets

- A new two-way protected bike lane (one-way southbound below E. 166th Street).

- Angled parking (to narrow the 56-foot-wide roadway)

- bulbouts at corners to shorten crossing distances

- East 166th Street from Jackson to Union avenues:

- pedestrian islands to shorten crossing distances.

- a new protected bike lane sheltered behind existing angled parking.

- East 165th Street from Tinton to Trinity avenues:

- A new two-way protected bike lane.

- New buffers on each side of the parked cars to narrow the 50-foot roadway.

- curb extensions to shorten crossing distances

- East 161st Street from Trinity to Tinton avenues:

- A new two-way protected bike lane protected by existing angled parking.

- curb extensions to shorten crossing distances.

- Tinton Avenue from E. 166th to E. 161st streets:

- A new protected bike lane.

- Elimination of wide median (which was often parked on).

- Narrower driving lanes.

- painted pedestrian islands to shorten crossing distances.

Standard painted bike lanes will also be added to:

- Trinity Avenue between East 161st and East 156th streets

- East 161st Street between Trinity and Cauldwell avenues and between Trinton and Prospect avenues.

- East 165th Street between Trinity Avenue and Boston Road and between Trinton and Prospect avenues.

- East 166th Street between Trinity Avenue and Boston Road.

(There will also be several roadways painted with sharrows, which are fundamentally useless, but at least indicate to drivers that cyclists will sometimes be present.)

And notoriously vicious Boston Road, between Third Avenue and E. 174th Street, has been designated as a “future” project zone — though the DOT would be wise not to tarry: Along that roughly mile-long stretch, 337 people were injured in car crashes between 2014 and 2018, with roughly 32 percent of them bicyclists or pedestrians. And of the 27 severe injuries and one fatality, 63 percent were cyclists or pedestrians.

Here’s a before-and-after (from Trinity Avenue) that shows what DOT is trying to accomplish:

In the end, the students learned another valuable, albeit depressing, lesson about the political life of New York City — even in a neighborhood where a tiny minority of residents own cars, everyone has to worry about parking spaces. Fortunately, this project has a net zero loss of spaces because so much angled parking is being added.

“The fact that it’s net zero made it easier, and the community board didn’t have the usual concerns that we’ve heard before,” Lopez said.

But that doesn’t mean the students didn’t see first-hand how local officials are skeptical of any street-safety project until they learn that parking won’t be affected.

“A lot of people in The Bronx have cars, so we understood that parking had to be kept,” Musa said, recalling the community board meeting he attended with the DOT officials in February. “If there were less parking, it just makes it harder on the people who need it.”