Secret Report Reveals that MTA Has No Interest in Verrazzano Bridge Bike Path

Secret’s out!

The MTA rejected several proposals for an affordable bike and pedestrian path on the Verrazzano Bridge and instead trotted a preposterously expensive alternative through a tainted focus group process — and ended up burying the whole thing in a report that was never released.

The process, revealed late last year in previously secret documents obtained by Streetsblog under a Freedom of Information Law request, show that the agency did not seriously consider two proposals by the bridge’s original designers to create simple and cost-effective routes for non-car users on the bridge and instead substituted a bloated plan costing hundreds of millions more.

And that’s where we remain today.

“People have been calling for non-motorized access to the Verrazzano bridge since it opened, but, today, the confluence of climate change, an uptick in biking, and a local economy that could use a boost, make a path more necessary than ever,” said Paul Gertner, founding chairman of the Harbor Ring Committee, which seeks a bike path on the bridge as part of a larger vision for a bike path encircling the city (its year’s-worth of letters to the MTA are archived here). The Verrazzano Bridge is the missing link in the 50-mile Harbor Ring loop, a bike path long sought by New Yorkers.

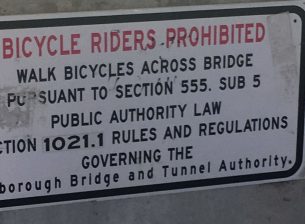

The latest saga of the MTA’s failure to add a bike path to the Verrazzano begins back in 1997 when the bridge’s original designers — Ammann & Whitney — were asked to analyze multiple schemes for a pedestrian and bike path on the fabled span, which has 13 lanes for cars and buses and not a single inch for pedestrians or cyclists.

The firm came up with multiple cost-effective possibilities, but recommended two above all:

- Turning the existing space between the suspender ropes on both sides of the upper level into seven-to-10-foot wide bike and pedestrian paths. The firm, calling this the most desirable plan and “a cost-effective pathway,” priced it at $23.8 million in 1997 dollars (roughly $38.5 million today). That figure includes approach ramps from the Brooklyn and Staten Island sides.

- Building paired 10-foot-wide paths as “wings” on both sides of the upper level. That plan, and the approach ramps, would have cost $36.4 million in 1997 dollars (roughly $59 million today). A version of this plan for the lower level was also rated “desirable,” though it would have cost a million more in 1997 money. (This is the plan version that has been favored and promoted by Harbor Ring for years.)

None of the plans was seriously considered by the MTA. Indeed, anyone who had any hopes for a Verrazzano Bridge bike path should have banished them decades ago, given that the 1997 report warned, even then, that “MTA has concerns about the safety and liability inherent in any strategy that introduces pedestrian and bicycle access to the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge [sic]” (emphasis added). Those “concerns” only hardened after 9/11.

Nonetheless, activists have continued to agitate for bridge access for pedestrians and cyclists, and the MTA dusted off its old report … then promptly abandoned it. Spending millions on consultants, the agency commissioned a new document — never seen before until Streetsblog’s FOIL request and embedded below — that revealed that by 2015, the MTA had created an entirely new plan: much wider (and therefore much more elaborate, engineering-wise) pathways to be built outboard of the bridge. Even though Ammann & Whitney’s narrower outboard lanes would have cost $54 million in 2015 dollars, the MTA’s new plan had ballooned to 20-foot lanes on either side of the bridge with a $320- to $370-million price tag.

That report was never publicly released.

“The MTA kept pushing off the release date for the report when we asked,” said Daelin Fischman, the co-chairman of the Harbor Ring Committee. “Obviously, we were curious given the unexpectedly huge pathways they were planning. It wasn’t until 2018 that the report was finished, and not until [the Streetsblog FOIL in] 2020 that we saw the report.”

The MTA’s design was also burdened by elaborate ramps to get cyclists and pedestrians from the waterfront greenway in Brooklyn to the bridge, rather than linking the path directly to existing roadways in Bay Ridge, which is much closer to the same elevation as the bridge’s eastern side (see schematic below).

More frustrating, the MTA never considered the most obvious solution to the problem: simply taking away one of the existing car lanes and converting it into a bike and pedestrian path. The 1997 report said it could be done — though no cost analysis was made — but by 2015, the MTA didn’t even mention that possibility in its report.

The MTA said its 2015 plan was based on the requirement that the lanes be sturdy enough to carry emergency vehicles, specifically fire trucks — a requirement that the MTA has said came from city fire and emergency response officials. Yet when Streetsblog asked to see “all correspondence between MTA divisions and the FDNY and NYPD about design requirements that those emergency agencies might have said they need for such a path,” the transit agency said, “After a diligent search, Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority does not have any responsive records.”

“That speaks volumes. A much-lower-cost lane on the lower level could be accessed by emergency vehicles from the outside traffic lanes,” Gertner said. “The main benefit to the MTA for having a bike lane capable of supporting trucks is for emergency access in case of vehicle crashes and to assist in general bridge maintenance. ‘Charging’ the full cost to cyclists is a false narrative that predictably elicited feedback that cyclists and pedestrians are not worthy of so much expense. The MTA should be honest and explain that most of the $320-plus million cost would benefit vehicles. Or, better yet, give us a $60-million ‘normal’ path without further delay.”

It’s also worth pointing out that bike and pedestrian paths on other MTA bridges — most notably the Triboro and Gil Hodges bridges — are too narrow for emergency vehicles yet operate just fine.

The agency ran its $320- to $370-million plan through a focus group that had already been influenced by media coverage of the “$400-million bike lane,” dooming the project for good.

“Some wondered why so many tax dollars would be going to accommodate a small group of cyclists,” read a summary of the discussion. Some participants also questioned the unsightliness of the ramps that would be required to accommodate the MTA’s bloated plan.

Tellingly, many participants asked about turning a lane of traffic into a bike lane rather than building a shared-use path — but that question “was accidentally not included in the first questionnaire version.” (Accidentally not included?)

Focus group attendees also claimed that not many people would use the bridge bike path for regular commuting — but there’s no way to know, given that the route is not currently an option (indeed, if planners only considered existing traffic patterns when considering new routes, they would never build any bridges at all on the basis that no one is crossing the river at that point currently).

When the MTA did mention the idea of removing a lane — which the agency had not even studied and therefore had not priced out — the focus group participants were quick to dismiss it.

“There was very little support for the idea of removing a lane of traffic and turning it into a bike lane,” the report said. “Participants said the bridge was already too congested as it is, and removing a lane would only intensify the problem.” (There is no data to support such a claim. It’s also worth noting that the bridge’s six lanes in each direction empty into highways of three lanes in each direction on both sides, so it’s unclear why the bridge needs such capacity when the roads serving it are so much narrower.)

“The MTA commissioned a very expensive engineering report and then asked participants about removing car lanes when that wasn’t in the report,” said Sophia Zhou, the co-chairwoman of the Harbor Ring Committee. “The report should have looked into this topic before having brought it up with participants. The MTA irresponsibly asked a question invoking a premeditated response from the focus groups.”

The overall goal of the MTA, activists say, was to bury calls for cyclists or pedestrians to be able to cross the Narrows, which has been sought by advocates for sustainable transportation since the bridge was completed in 1964. After rejecting the 1997 feasibility study and presenting its own 2015 analysis of its own bloated designs, the MTA promptly ignored all requests to allow the public to scrutinize the agency’s process, finally yielding after the Streetsblog Freedom of Information request.

Activists say they’re not surprised, given the amount of time they have been fighting for the path.

“For decades, we have made the case for this project’s immense environmental, economic, and recreational benefits, and it’s long past time for the MTA to produce a cost-effective plan for this project,” said Rose Uscianowski, Staten Island Organizer at Transportation Alternatives, which, along with Bike South Brooklyn, is working closely with the Harbor Ring Committee. “We urge Gov. Cuomo to step up, right this historical wrong, and deliver a world-class pedestrian and bike path over the Verrazzano Bridge.”

Bike South Brooklyn’s petition is here.

We reached out to the MTA several times for comment for this story. After initial publication, the agency provided additional background that Streetsblog is still going through and will be the basis of an entirely new story. For now, here are the MTA’s on-the-record comments:

Daniel DeCrescenzo Jr., president, MTA Bridges and Tunnels: “Traffic on the MTA network is back to near pre-pandemic levels. There is not spare capacity on the bridge to take away a lane from motor vehicles without gridlocking the bridge for bus customers, trucks and motorists.”

DeCrescenzo: “Safety of our customers is the most fundamental value of the MTA. Over the years that a path would be in service, it’s almost a certainty that at some point a cyclist or pedestrian would suffer a medical episode, collision or even be victimized by crime while on an isolated miles-long path that requires significant climb. Quick access to an emergency vehicle could mean life or death for that cyclist or pedestrian. Any number of verbal communications between staff at FDNY and NYPD and the MTA reaffirm all agencies are aligned on this fundamental commitment to safety.”

Beyond that, and our forthcoming story, this story is based entirely on MTA documents, so there’s that. The key document is below:

![A preliminary report from the MTA shows new bicycle and pedestrian paths on the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge are feasible. Advocates want to work with the MTA on the details. Image: WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff for MTA [PDF]](https://i2.wp.com/nyc.streetsblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/VNB_PATH.png?w=998&crop=0%2C0px%2C100%2C589px)