Op-Ed: Making Black Lives Matter in Street Safety

The institutions and organizations of activist transportation must reflect the communities for which they are advocating.

The Black Lives Matter protests of recent weeks have brought national and international attention to a long-standing movement to confront and address the inequality and structural racism embedded in our society. This social and economic movement (in the last century, we called it “civil rights”) seeks to vanquish anti-Blackness and white supremacy and enshrine respect and human dignity for every person regardless of race, but specifically for Black people — and it is scrutinizing every system and organization.

At the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, we have been working for more than 50 years in order to close the racial-wealth gap, address the social determinants of health, and build a more equitable and inclusive Brooklyn. In that work, we have intersected many times with the advocates and organizations of the safe-streets movement, on creation of new public plaza, streetscape projects — and especially the expansion of bike share.

The transportation world must actively move beyond performative “wokeness” and drive real change to diversity, equity and inclusion. Its advocates must take a hard look at who leads, who decides, who benefits, and who is harmed by our definitions of safe streets and our active-mobility infrastructure, and they must lift up the voices of those who now are not being heard (but who are affected) by the initiatives of the movement.

Those who advocate for safe and open streets have a historic opportunity to redefine the tent so that Black and brown people who heretofore have not felt welcome in the safe-streets movement nor seen the value of an alignment with it will see an ownership stake.

As I have said before, when I first began working with Citi Bike and other partners on bike-share equity, I was skeptical — not just of bike share but also of the active-transportation movement itself. The people I saw leading the conversations about safe streets, including at Transportation Alternatives, where I have since joined the board of directors as the first African American woman to serve, did not reflect the communities for which they were advocating.

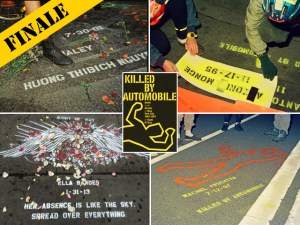

The faces are slowly changing — as is the definition of safe streets. At long last, transportation advocates are acknowledging that their work must encompass the notion that safety in public space is experienced differently by people of color — that, for Black and brown bodies, safety in public space means freedom from being overpoliced and, worse, murdered.

We all see the value of our streets, bridges, parks and plazas, which are being claimed as spaces for protest and freedom of movement, as embodied in the “BLACK LIVES MATTER” mural painted on Fulton Street in front of Restoration Plaza. Yet street safety does not hold the same meaning for everyone — nor lead to the same priorities. To people of color, protected bike lanes might take a back seat while we seek freedom and safety in such everyday activities as parking a car, bird-watching in the park, or getting some exercise by jogging.

Advocacy organizations, donors, institutions, and governments should examine their procurement, hiring, board recruitment. Who sets the table? Who is speaking and what voices are lifted? Who receives opportunities for jobs, business and funding? In short, how are you spending your dollars? Ensure that your actions align with your values and messages.

In some cases, space might need to be ceded at the table to make room for others. For too long, people of color have not had these kinds of opportunities. For every contractor, board member and prospective employee interviewed, we must look harder, expand networks, and stack the deck with candidates of color to ensure ample opportunities at all levels, from entry level to management leadership.

Further, we must create pathways for growth. Potential allies are all around in Black and brown communities; we walk and we bike, whether we are walking to the bus stop or biking around the park. Find us; include us; hear what we think is important. Encourage new voices so that we are leading the conversations.

We also need to understand the interconnectedness transportation equity requires. As I wrote in an op-ed for Gotham Gazette last year, “We must remember that advocacy around transportation equity is part of a larger effort to stem the tide of historic disinvestment across many facets of life in communities of color.”

At Restoration, we focus on the racial-wealth gap, because we believe it is the root of today’s racial disparities in health, wealth, home-ownership, educational attainment and incarceration rates. Transportation equity, therefore, must contribute to wealth and economic opportunities for those indigenous to communities so that they can remain and thrive in their neighborhoods — without fear that they will be displaced by gentrification.

COVID-19, directives to shelter in place and social-distancing guidelines, have spurred the momentum for open streets. New Yorkers crave space for physical release and for our mental health — really, for our basic survival in a socially distanced world. As we build campaigns for open streets and rethink street design, we must look to redress systemic issues and ensure that the benefits accrue to those who have been barred from opportunities.

We need to ask: How can campaigns and plans be created with communities instead of for them? Is this what people want? What are other needs and priorities in the community? How can we include those needs in the plan? This means taking a fundamentally different approach to planning than we take today — and some institutional structures will resist such changes. If we work together, however, we can overcome these constraints, and the rewards will be immense.

Safe streets, more humane bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, and affordable transit options are extremely important, but if we fail to use a racial-equity lens and don’t listen to communities, our wins won’t be everybody’s wins, and we will further divide our communities instead of connecting them.

Our racial-equity lens must foster real policies that can be regularly evaluated and measured. Of course, we won’t get everything right immediately, but if we are committed to transparency and self-examination, we can correct course along the way.

Tracey Capers is the executive vice president of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation (@BSRC) and a board member of Transportation Alternatives.