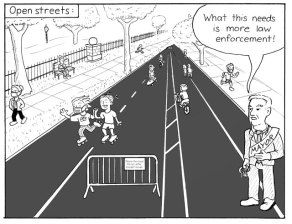

De Blasio Looks Forward to Expanding ‘Open Streets’ — But Raises Specter of ‘More Enforcement’

The launch of the city’s “open streets” program on Saturday was a success that required very little involvement of the NYPD — but even as he promised to expand the effort, Mayor de Blasio said that process might be complicated by the need for more cops because he is “still fundamentally a believer in enforcement in all things.”

The mayor’s comments came Sunday morning just as the second day of 7.1 miles of car-free streets were set to begin for a second day — and they came in response to a question from Streetsblog about why the mayor felt comfortable beginning the program with virtually no cops. Heavy staffing demands by the NYPD ultimately sunk the mayor’s first open-streets effort after just 11 days — and the NYPD and DOT had testified before the city council just nine days ago that open streets were “not possible” without a massive police effort.

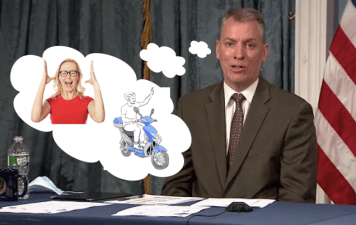

Here is the exchange between Streetsblog and de Blasio:

Streetsblog: On the open street launch, Mr. Mayor and obviously Commissioner Shea, it was very noticeable how few NYPD officers or crossing guards were needed to safely create space for the public. We talked to DOT Commissioner Trottenberg, who said the administration’s thinking had “evolved” on open streets since she and the NYPD testified that such a plan was impossible. Clearly yesterday proved that it is possible. So talk us through the administration’s evolution on policing open streets — and did you get a chance to experience one of the open streets yesterday?

Mayor de Blasio: I am still a fundamentally a believer in enforcement in all things. We had a good first day with a limited sample size. I don’t think anyone yet can say that we know exactly what it’s going to take to enforce these things going forward. But I can say one absolute evolution is that a few weeks ago, we did not know what kind of capacity we’d have in terms of returning officers and how many would get sick. … We’ve seen a lot of progress on that front, that means we have a lot more ability to enforce and it gives me a lot more comfort going forward on these open streets. But Day 1 from what I could see. Went well. We’re looking to expand, but it always will require enforcement. We’ll find out how much by doing it. It’s also fair to say that more and more knowledge of the open streets and the warmer weather, that’s when people will come and where you do need enforcement for sure. [It’s] definitely a good day and a good concept and we look forward to broadening it.

De Blasio has promised to create 100 miles of open streets, starting with 40 miles in May. The launch on Saturday started with what activists called the “low-hanging fruit”: roadways inside parks and next to parks — most of which could easily have been made car-free long ago. If the mayor is truly committed to heavy police presence, it is unclear how the additional 33 May miles and 93 total miles will be achieved.

But it is also telling that NYPD Commissioner Dermot Shea did not respond to the question, suggesting that, for now, at least, DOT is running the open streets program, which was previously overseen by the police, as Streetsblog reported.

The mayor did say that he liked what he saw from the first day.

“I saw the open street on Prospect Park West and it looked like things were going well,” he said. “[First Lady] Chirlane [McCray] reported that the open street by Carl Schurz Park was going well.”

But his larger answer suggests continued caution. And it remains unclear what Hizzoner will do at the end of this crisis, when the city could be re-imagined as a place for people, not cars. New York Times columnist Ginia Bellafante raised the bar with a Sunday column accusing the mayor of cowardice in the face of one of the most profound public health opportunities in city history.

“Advocates for livable streets have had a hard time understanding why the police would be so critical to the venture,” she wrote. “Crises of the kind we are experiencing require nimble and innovative thinking, the willingness to break with frameworks of the past. The slow implementation of a measure that seems at once relatively simple and destined to provide so much good, offers one more example [of] bureaucratic inertia. If we can’t quickly summon cars off the street — and only some of them and just provisionally — at a time when no one is going anywhere, how can we expect the city to brilliantly and flexibly reimagine itself once the pandemic is over?”

The mayor’s answer on that has been, “We can’t.” Indeed, in naming eight “recovery panels” last week — including panels for business, arts, and public health — the mayor left off one crucial sector of New York City life: transportation.

Meanwhile, other cities are planning ahead so that when their cities get back to “normal,” it’s not the old normal of congestion, pollution and hundreds of easily preventable road deaths.

Seattle, for example, is opening 20 miles of residential streets as part of its healthy streets plan during the COVID-19 epidemic — a program that is already seen as so successful that it may become permanent, the Emerald City’s Department of Transportation Director Sam Zimbabwe told the LA Times.

And Paris — which is run by de Blasio’s friend Anne Hidalgo — is planning so aggressively that City Lab recently headlined its coverage, “Paris Has a Plan to Keep Cars Out After Lockdown.”

It is “out of the question that we allow ourselves to be invaded by cars, and by pollution,” Hidalgo said.

For now, at least, it is very much in the question whether New York will enshrine or eradicate open streets when this is all over.