BATTLE LINES: Manhattan Panel to Discuss ‘No Free Parking’ Resolution

Community Board 7 will take up a call for a study of existing curbside use. Car owners see evil forces coming to steal "their" parking.

One of the least-controversial measures in the history of community boards will come before a Manhattan full board on Tuesday night — so why are both sides stocking up on fire extinguishers?

Because the simple resolution before Community Board 7 — neutrally titled, “Request for a Study on Curbside Usage” — has become a proxy fight in safety activists’ larger war on free on-street storage of privately owned vehicles in the public right of way.

Car owners call that “parking” — and they don’t want anything to affect it. And on the eve of Tuesday’s vote, they are lining up to oppose even a city study seeking more information about how congestion pricing might affect current residents and those outside the neighborhood who might suddenly start cruising the neighborhood looking for parking.

There’s a long backstory here — eight months of public bickering, plus two secret, closed-door, invite-only meetings held by the local council member last week — and activists on both sides of the issue are digging their trenches. So before we preview the fight to come, it might be best to first review what will actually be debated. No matter which side you’re on — whether you think free parking is a New York City birthright or you think there are better ways to allocate the curb in an age of congestion, next-day deliveries, and climate change — just read the resolution and ask yourself, “Is this really so controversial?”

Request for a Study on Curbside Usage

- Our community currently suffers from traffic congestion, rampant double parking particularly due to growing e-commerce deliveries, significant “cruising” for parking and a substantial number of injuries to street users. [No one disagrees about this.]

- Congestion pricing is scheduled to be implemented in approximately one year and community residents and business owners have expressed concern about the impact of this new policy. [This is a statement of fact.]

- How we use our curbside space has remained largely unchanged for many decades while our city has changed dramatically. This city-owned land should be used for the greatest good for the greatest number of people, with a particular focus on the needs and concerns of the residents and businesses of our community. [Anyone got an electric opener for that can of worms?]

- THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED THAT Community Board 7/Manhattan requests that the city: (1) assess current policy regarding parking and curbside usage, (2) advise us as to whether there are policies that could provide greater benefit to the community, improve traffic flow and promote safer streets, including, but not limited to, paid residential parking permits, metering with surge capability and strategies learned from studying the practices of other major cities, and (3) conduct studies both before and after the implementation of congestion pricing to establish its effect on the community. [Reminder: this is a call for a study.]

The can-of-worms paragraph is where a lot of the bodies are buried in the current debate. Supporters of free on-street car storage suggest that it’s a misguided notion that curbside space is “city-owned land” that can be reallocated as situations change. They believe it is their space. They see any call for a “study” as a dog-whistle.

In the interest of explaining that point of view, Streetsblog asked Tag Gross, who runs the website Common Sense Streets, about why car drivers are so possessive of curbside space — and why car owners should be accommodated when only 27.3 percent of households on the Upper West Side own a car. Let’s quote Gross in full (passages marked with an asterisk represent assertions for which Gross did not provide any documentation and Streetsblog could not independently verify):

About 35 percent of the residents on the Upper West Side live in those households (the bigger the household the greater the likelihood of a car. Well over 50 percent of the households of four or more own cars*). So families will be negatively impacted by a further reduction in available parking. Seventy-thousand residents of the Upper West Side live in homes with cars*. That’s not “tiny.”

These are people with major emotional and financial investments in their homes and the community that were made based on what is legal and proper* going back 70 years. In fact, these are the residents that are responsible for making the Upper West Side the desirable neighborhood that it is*. Even non-owners, for example, can stay here knowing that their friends and family can easily reach them from the outer boroughs and suburbs. Others stay knowing that their family members in suburbs are within reasonable reach because their cars let them get to their families in 40 minutes instead of two hours. How much thought have you given these people?

[Editor’s note: Gross often asks questions when responding to questions. We told him in the interest of transparency, we would answer his questions publicly. In this case, we think a lot about how people get around — one might say it’s all we think about. And no version of this resolution has called for the elimination of driving, just free on-street parking. And in the end, we tend to devote more energy towards finding solutions to the problem of how huge masses of people, not small numbers of people of greater wealth and privilege, get between Scarsdale and Zabar’s on a Saturday afternoon.]

Gross continued:

Census data confirms that about 13 percent of the working population in our community works outside Manhattan, and drive to work in a reverse commute. The use of cars is essential to their employment as mass transit is not an option.

Gross’s 13 percent figure appears accurate. But his position that cars are “essential” to getting workers from the Upper West Side to other boroughs (roughly 8 percent of workers) or out of the city (another 5 percent) — and that transit is “not an option” from a neighborhood with seven subway lines — is preposterous. More than 92 percent of Upper West Side workers get to work with transit, their legs, their bikes. Only 5.8 percent drive themselves. The ones who leave their cars behind have merely commandeered public space so they can store their car for future use — such as to “escape from New York,” as Gross has said before.

Gross’s defense of the entitled driver class goes beyond his comments to the Common Sense Streets website, where he claims that a loading zone pilot project had “failed” — when in fact it has worked exactly as designed: there is less double-parking on West End Avenue as a result. It has only been a “failed” from the perspective of drivers who are looking for the handful of parking spaces that are now being used by package delivery truckers who would otherwise be blocking the roadway for other drivers. (Gross declined to comment on loading zones, saying, ” The issue at hand is congestion pricing and its impact on CB7.”)

All of that said, a portion of Gross’s concern about Tuesday’s resolution stems from his lack of trust in the board’s transportation committee, which is chaired by Howard Yaruss.

Yaruss’s initial resolution last spring — which stated that “the city’s current policy of allowing the vast majority of street space adjacent to curbs to be used for free parking needs to be revisited regardless of th[e] effect of congestion pricing” — was deemed so hot that it needed to be tabled and, eventually, watered down to the matter on the agenda Tuesday.

Gross claims not to oppose the resolution that will be debated on Tuesday, but doesn’t trust his neighbors who want to reclaim some public space for use by the car-free majority.

“We are concerned with this resolution given the history and background and the fact that it makes requests for specific focuses that are clearly anti-car,” he said. “We’re for finding common ground on issues around safety, noise, pollution, traffic, residential parking, e-commerce deliveries etc. but you do not do that by using congestion pricing as an excuse to try and eliminate curbside parking, excluding alternate points of view or by pitting neighbors against each other.”

(For his part, Yaruss told Streetsblog, “Some people have alleged that I have a conflict of interest. I freely admit I own a car and drive regularly. That said, I am confident in my ability to be fair and reject any allegation of bias because I own a car.”)

Supporters of the resolution dispute Gross’s framing and say that the best way to build “common ground” is to demand that the city study the impact of congestion pricing mere months before it is scheduled to start.

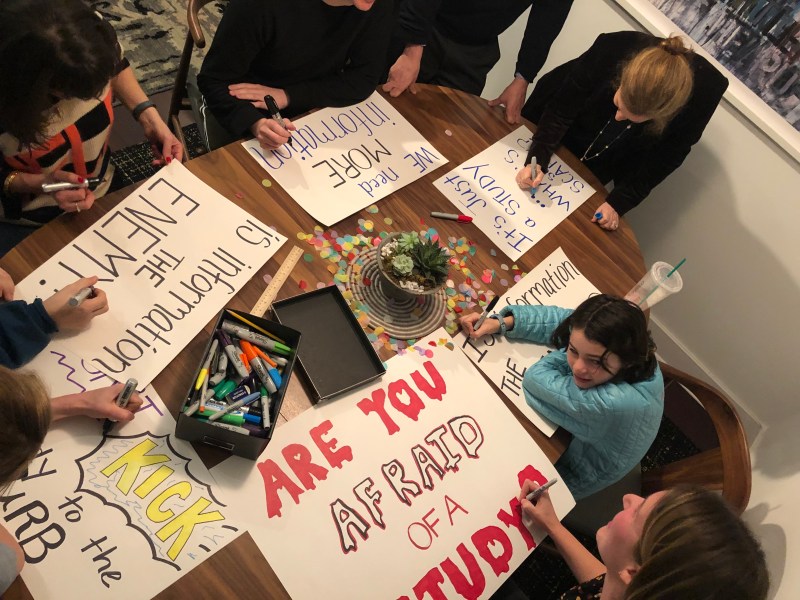

That’s why members of the neighborhood’s car-free majority spent hours over the weekend making signs for Tuesday’s meeting, several reading, “Are you afraid of a study?” (with the word “study” in the drippy, blood font popular in horror movie posters).

Streetopia UWS Director Lisa Orman is a supporter of the study, but added she has been appalled at how car owners like Gross have demagogued the issue and gotten the community board to hand-hold the car-owning minority. Indeed, Gross had not signed up for the two closed-door meetings held by Council Member Helen Rosenthal on Wednesday and Sunday, yet he was allowed to attend while others who had not signed up were denied entry.

Those meetings were dominated by discussion of how the community board would undertake Tuesday’s meeting to ensure that both sides are heard — to the point of perhaps capping the discussion at 25 supporters of free parking and 25 opponents of it (a weird balance in a neighborhood where the vast majority of residents are car-free).

“The rhetoric from Tag Gross and other free parkers, who continue to flier our neighborhood with inaccurate, inflammatory calls to action, shows us just how important this entitlement is to them,” Orman said. “The sad part is that there are plenty of ways that we could improve the public realm for the vast majority of Upper West Siders — think busways, daylighting, neckdowns, bike corrals — but we continue to debate whether or not we can even study the status quo.”

Oman sees the curbside space differently than Gross, and is urging her neighbors to attend the meeting and share their own version of a streetopia.

“Would you like less congestion on your streets? How would that change your life? How about less double-parking? What about the safety benefits of daylighting every corner? Or, dare I say, what about the social benefits of calmer traffic and places to sit and chat with your neighbors (not just on alternate side parking days)? Your voice matters, too,” she said.

At the end of the day, it’s no mere conspiracy theory of Tag Gross to think that the neutrally worded resolution is the beginning and end of this debate. Indeed, the study will likely reveal that the current allocation of curbside space is grossly imbalanced towards the least-efficient use: the storage of cars that are rarely used. Once that finding is confirmed, the study will set in motion a chain of events that will force the city to finally address how the current curbside allocation touches on all the conditions that everyone agrees are bad: congestion, unsafe roads, poor transit, garbage inches from already crammed pedestrians and, in general, unlivable streets.

Car owners like Gross want to keep everything the way it is, with their vehicles dictating how street space is allocated. Supporters of the resolution envision streets with wider sidewalks, safer bike lanes, freely flowing crosstown bus routes and less congestion because fewer people are cruising around looking for parking. And they think that a study is the first step.

Which side are you on? We know where the mayor is — on the car owners’ side.

“If we’re going to tell people they can’t park on their street, no, that does not ring true to me,” he told reporters in November, when he was last asked about the resolution. “I think we need to keep finding every solution to reduce the use of motor vehicles in New York City, and I’ll look at a whole range of things, but if you go so far as telling people they can’t park on their street, no, I’m not there.”

Community Board 7 at Congregation Rodeph Shalom, 7 W. 83rd St. between Central Park West and Columbus Avenue, Tuesday, Feb. 4, 6:30 p.m.