Good News/Bad News: MTA Has A $50B Capital Program — But It’s Still a State Secret

The MTA might be getting ready to hit Fast Forward. Or maybe not. The public simply doesn’t know.

A single slide in the latest version of the MTA Transformation Report (below) revealed this week that consultants AlixPartners, which is helping reorganize the MTA, have seen a draft of the 2020-2024 capital plan — and that it totals somewhere around $50 billion over five years.

That’s an important number: New York City Transit President Andy Byford’s 10-year “Fast Forward” plan to modernize signals, elevators and other aspects of the subway system, is supposed to cost somewhere between $40 and $60 billion.

So even if the draft plan remains a state secret, the amount, at least, made sense to transit activists.

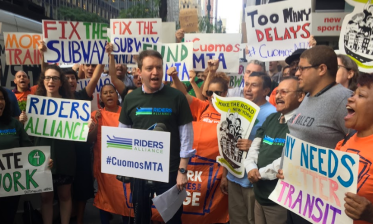

“Fifty-billion dollars sounds like it’s in the ballpark for what it takes to stay on track with the pace of Fast Forward,” Danny Pearlstein of the Riders Alliance. “What’s important about that spending for riders is that signals, subway cars, elevators are the essential upgrades that New Yorkers need for a modern reliable subway.”

(The chart above describes the spending pattern in the draft capital plan for 2020 to 2024. In the paragraphs next to the chart, AlixPartners notes that the first year of the plan “includes $10.7 billion in forecasted commitment” on capital spending in 2020. In 2021 and 2022, the chart shows commitments of just under $12 billion, before dropping back to $10 billion-plus range in 2023 and just over $5 billion in 2024. Capital plan spending is funded by entities like the federal government, state government, city government and the MTA itself, but money committed money in a particular year isn’t guaranteed to be delivered.)

Pearlstein noted that he was reacting to the number that was attached to the draft plan, and said that the public and outside experts needed an opportunity to review the plan, and said that “some kind of transparency is the most important” part of the process in building the subway spending blueprint. The MTA press office declined to comment — not a good sign.

Good government advocates also pointed out that just because there’s a draft plan — which consultants, but not the public, have seen — doesn’t mean we know where the money could actually go.

“We don’t know the priorities, or to what extent Fast Forward is included,” said Reinvent Albany’s Rachael Fauss. “It means things are still very secretive. It doesn’t mention how [the MTA] is going to meet the prior commitments in previous plans, and the AlixPartners report opens up a lot of questions on what the MTA’s intentions are with their prior commitments.”

The 2015-2019 capital plan is in its final year, but huge amounts of the current plan will most likely have to be rolled over into the capital spending the MTA does in future years. Less than half of the money for the current $32-billion capital plan has been delivered so far — so there’s a shortfall right there.

Reinvent Albany noted that the MTA Board has an obligation to approve the 2020-2024 capital plan by Oct. 1. But the MTA’s 20-year-needs assessment, a document that’s supposed to lay out where the agency has to spend its money, won’t be released until after this year’s capital plan is supposed to be voted on. In addition, there are other conflicting deadlines with the upcoming capital plan. The Traffic Mobility Review Board, which is charged with setting up New York City’s congestion pricing scheme, is supposed to get a chance to review MTA capital plans. One major problem: That panel hasn’t even been set up yet, let alone staffed up.

“It’s a political problem, because there’s so much in flux at the agency and in general things are held close to the vest until right before a decision is made. Because of these deadlines and reviews and studies there’s a layer of chaos that’s not helpful,” Fauss said.