Dangers Mount With Crashes, Conflicts on Queensboro Bridge

The city should separate cyclists and pedestrians — stat! — before someone gets killed. But motorists, as always, come first.

Is the Department of Transportation just waiting for someone to die on the 59th Street Bridge?

For some reason the city is ignoring warnings that dangerous conditions and a growing number of crashes require the immediate separation of cyclists and pedestrians on the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge — because officials don’t want to inconvenience motorists.

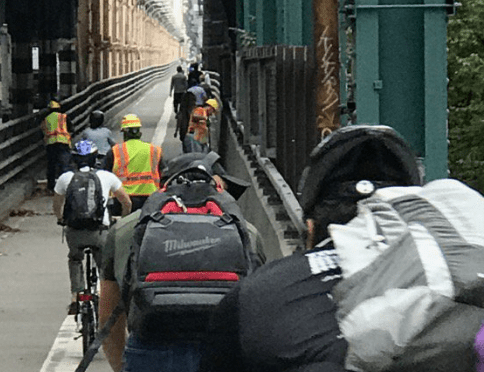

The bridge, the only bike/pedestrian route between Queens and Midtown Manhattan, is a lifeline for many working cyclists, yet they and pedestrians now share a narrow and crowded lane along the the span’s North Outer Roadway — separated only by a painted line. The lane is so claustrophobic that it narrows at one point to a mere nine feet — which is even less space than the notoriously packed Brooklyn Bridge footpath.

Given the crowding, activists for more than a year have been urging the city to repurpose an underused car lane, the South Outer Roadway, for sole pedestrian use.

The DOT says it is studying the idea, but claims that it can’t move until 2022, when it will complete its reconstruction of the bridge’s upper roadway. Until then, it says, the south outer roadway must compensate for lost vehicular capacity on the span.

Cars, meanwhile, have nine lanes on the Queensboro Bridge.

(A DOT spokesman confirmed to Streetsblog: “Due to upcoming work on the Queensboro bridge, the South Outer Roadway will be needed for vehicle diversions during construction. During this time, DOT will continue to evaluate different lane scenarios to understand the impacts and modifications that would be required to convert the SOR to a pedestrian path and use the North Outer Roadway as an exclusive bicycle facility. If found to be feasible, this conversion could be timed to coincide with the completion of the construction work.)

Studying? DOT ought to act now — before someone dies on the shared bike/pedestrian lane. Three years is too long a wait considering the number of crashes, near misses, and harrowing crossings cyclists and pedestrians experience every day. But apparently, for DOT, safety takes a back seat to potential traffic congestion.

It is hard to quantify this jump in collisions. Queens Transportation Alternatives activists established a bridge crash-reporting tool in May 2018, and some entries are frightening. Crashes — some with injuries — happen daily. Twitter abounds with crash sightings. The city’s Vision Zero initiative, however, does not track crashes on the bridges (a most curious omission given that many occur there), and NYPD only counts motor-vehicle collisions on the spans.

But NYPD traffic stats for Manhattan North, which encompasses the Queensboro Bridge, show an 11.2-percent jump in cyclist injuries so far this year compared to last year, to 269 from 242. On the Queens side, Queens North stats show an even bigger jump in cyclist injuries, 12.9 percent, to 325 from 287. So while we can’t number the injury-producing bike crashes on the bridge, the general trend bolsters our anecdotal information.

When the bridge opened in 1909, it had room for vehicles and four streetcar tracks on the lower deck and a wide pedestrian promenade above. In 1917, two subway tracks were added to the upper deck, connecting the Astoria and Flushing lines (today’s N/W and 7 trains) to the long-gone Second Avenue Elevated Line in Manhattan. This turned the bridge into a people-moving machine, with a capacity of more than 300,000 a day.

Over the years, however, the city turned almost all of the bridge over to cars and trucks. In the 1930s, it gave part of the upper deck to cars; after the demolition of the Second Avenue El in 1940, it gave cars the entire upper span. Over the years, capacity fell from 326,000 in 1940 to 248,000 in 1989, a 24 percent drop.

Trolleys ran on the lower-deck outer roadways until 1957, when those lanes, too, became car lanes. The bridge then became vehicles-only, reducing capacity by 15 to 20 percent and leaving no way to get from Queens to Midtown except by car, bus, or subway.

I know: In the 1970s, I was living in Queens but worked as a bike messenger in Manhattan — and had to maintain a bike in each borough!

During the 1980s, after many protests, DOT first converted the south outer roadway (briefly) then the north outer roadway to cyclists/pedestrian use. The department opened a greenway for cyclists and pedestrians on the bridge’s Queens side in 2011, a boon for safety and convenience. It further improved bridge bike access in 2016 with the inauguration of the First Avenue bike lane between 57th and 60th streets in Manhattan.

But the progress isn’t enough. Bike/pedestrian traffic on the bridge grew 21 percent from 2011 to 2016, to more than 5,000 bike trips a day — and will likely grow even more with residential development in Long Island City.

It’s not just the overcrowding. Other design flaws hurt bridge safety — including confusing signage and signals, pedestrian/bike/traffic conflicts on both sides of the span, and blind curves and poor lighting in spots.

On the Manhattan side, these flaws include:

- The bridge’s First Avenue entrance intersects the protected bike lane there, which goes two ways for the block between East 60th and East 59th Street, so cyclists entering and exiting the bridge cross paths with those going north on First Avenue.

- Meanwhile, cyclists going south on First Avenue who want to enter the bridge must make a 180-degree turn — in car traffic — eastbound from East 60th Street onto the bridge’s bike entrance, which runs westbound via a protected lane on the south side of East 60th. All this must be accomplished while mixing with pedestrians and deciphering confusing signs and traffic lights. Often, cyclists wind up running a red light at East 60th Street and First Avenue — a fact that has not been lost on ticket-obsessed cops.

- The shared bike/ped path narrows from 11 to 9 feet as it begins a steep descent above York Avenue. The bike lane shares space with the car ramp down to First Avenue, which has a steeper descent than the main bridge roadway. Bad, often broken, lighting, makes for a huge hazard during evening rush hours in late fall and early winter.

- Cyclists and pedestrians going up the incline are also blinded by car headlights on the First Avenue ramp, which is just over a low wall. Cyclists and e-bikes speed down the steep ramp as cyclists struggle slowly up the ramp, with pedestrians squeezed into a four-foot space. At the base of the ramp, a 180-degree hairpin turn creates a blind curve as the lane doubles back to First Avenue.

On the Queens side, the flaws include:

- The vehicular entrance to the lower deck crosses the greenway at Crescent Street. Traffic entering the bridge sometimes backs up across the greenway, blocking it even when the light is green for cyclists. As the video above shows, buses traveling west on Queens Plaza North also enter the bridge here, making a left across the greenway on the same green light as cyclists. This signaling is problematic, but most bus operators look out for cyclists. The turn is illegal for everyone else, but cars and trucks often do it anyway.

- Cyclists entering the bridge from the west make a left from the greenway onto the bridge; meanwhile, cyclists exiting the bridge to go west on the greenway make a left, 180-degree turn across the path of entering cyclists. The exiting cyclists, coming off a descent, often are traveling fast. Add pedestrians — and dangers multiply.

DOT is well aware of these flaws. Queens activists have walked and biked the bridge with senior DOT staffers.

TA Queens’ ongoing campaign to convert the south outer roadway for pedestrians has obtained the signatures of more than 2,000 individuals and 100 business owners and the support of Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer. The conversion would make the Queensboro Bridge paths like those now on the Manhattan and Williamsburg bridges.

Transportation Alternatives also conducted AM and PM rush-hour surveys showing that the number of bikes and pedestrians using the North Outer Roadway already exceeds the number of vehicles on the South Outer Roadway.

The pedestrianization plan also would stimulate business in Long Island City. For tourists, those south outer roadway skyline views could rival those of the Brooklyn Bridge.

If it were just a matter of convenience and aesthetics, though, we could wait out the three years of bridge reconstruction. But people are getting hurt. Lives are more important than a few minutes’ delay for motorists. So what’s the hold up?

DOT, do the right thing.

Steve Scofield is a Transportation Alternatives activist in Queens.