Vision Zero Itself Goes on Trial in the Bronx On Wednesday

The battle over Mayor de Blasio's signature street safety initiative was set in motion last month when a Bronx judge blocked the city from implementing a plan to tame drivers on a 31-block stretch of Morris Park Avenue.

A group of Bronx business owners will go to court on Wednesday to do more than just halt the city’s safety redesign of Morris Park Avenue — the group wants to put Vision Zero itself on trial.

The battle over Mayor de Blasio’s signature street safety initiative was set in motion last month when a Bronx judge blocked the city from implementing a “road diet” plan to tame drivers on a 31-block stretch of Morris Park Avenue. Judge John Higgitt accepted the plaintiffs’ argument that the project, which was the fruit of months of public hearings and safety studies, still needed more review.

That review will begin tomorrow at Bronx Supreme Court.

The facts in the case are fairly straightforward. The city argues — and has data to support said argument — that Vision Zero road redesigns save lives, reduce injuries and encourage cycling. The Morris Park Avenue business owners — Coqui Sales Appliance, Window King, Morris Park Bake Shop and Captain’s Pizza — believe that the redesign will hurt their bottom line.

In court papers, the businesses — plus the Morris Park Community Association and Council Member Mark Gjonaj — make several typical NIMBY claims: they argue that their concerns were not heard (though there were several public hearings on the matter, plus private meetings between DOT officials and local electeds); they claim the strip in question, between Adams Street and Newport Avenue, is not unsafe (even though 426 pedestrians and cyclists, plus hundreds of drivers, have been injured, with one fatality, since 2010); and that Window King “will be forced to close” if the traffic pattern of Morris Park Avenue is altered.

But the opponents’ court papers go beyond the parochial issues of a local street design to challenge the very notion of Vision Zero itself.

“[The] Vision Zero initiative is solely [the city’s] own administrative creation, or quasi-administrative because it was not authorized by legislative authorization or directive,” the businesses argue. “Vision Zero is based upon information and data about traffic safety to inform decision-making, but is not based upon regulatory, administrative, or local law authorization or guidance regarding the process and procedures to develop and implement the initiative.”

The opponents’ court filing concludes, “The Vision Zero initiative…to implement that Morris Park Avenue Safety Improvement Project is without reason, a rational basis, and is arbitrary and capricious and thus illegal and unlawful.”

Higgitt’s temporary restraining order merely barred the city from doing any work on the so-called “Morris Park Avenue Safety Improvement Project” until the matter could be resolved in court.

The city says it is not worried.

“The court has not fully weighed in on the merits of these claims,” said Law Department spokesman Nick Paolucci. “We stand by this carefully thought out project which will save lives. We will mount a vigorous defense.”

Indeed, the city’s paperwork makes a strong case that it should be allowed to do what it is required to do under law: make the streets safer. The city’s response to the business owners’ paperwork has an unmistakable undertone of frustration.

“This … proceeding stems from dangerous traffic conditions — rampant speeding, numerous crashes resulting in serious injuries and a fatality — on Morris Park Avenue in the Bronx,” the city filing states, identifying the roadway as a “threat to public safety.”

“Rather than supporting this street improvement project, petitioners seek to derail it,” the city adds.

Court documents also argue that the city charter gives the Department of Transportation “broad authority over the functions and operations of transportation in the city and especially over matters and requirements essential for traffic and street safety.”

The city also argues that its street safety improvements can’t possibly be arbitrary and capricious because “a rational basis exists for the administrative determination.”

That “rational basis” should be the bottom line for all residents of all neighborhoods: safety.

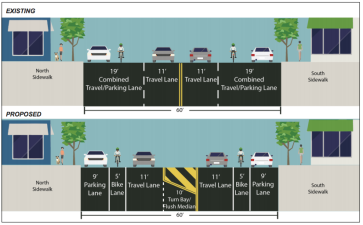

Morris Park Avenue is a dangerous roadway. According to the DOT, 61 percent of motorists exceeded the speed limit in a spot check this spring, up from 27 percent in a similar check in 2014. From April 2018 to April 2019, 82 people were injured in crashes on the roadway. Double-parking is a persistent problem, and the absence of left-turn bays causes drivers to shift from one lane to the other to avoid turning cars, which causes tie-ups.

The city’s court papers also take aim at Window King owner Nick Ferraro, who argues in court papers that he receives a delivery of 150 to 200 windows once a week — a delivery that requires his supplier to double park in front of the firm to unload the material, a process that takes three to five hours. Ferraro claimed in court papers that his supplier, whom he does not name, has threatened to halt deliveries if the redesign goes forward.

“It defies logic that a supplier providing up to 200 windows per week would walk away from that business,” the city argues in its latest filing on May 22. “Moreover, Window King’s current practice of a three- to five-hour delivery while the delivery trucks are double-parked in a lane of traffic is illegal. Illegal activity can hardly be the basis for irreparable harm.”

The city’s court papers are below: