Never Stop Stopping: Removing Bus Stops Isn’t Easy — In New York City or Anywhere Else

The MTA desperately needs to attract more riders to its painfully slow buses. One of its methods — removing bus stops — is drawing ire on Manhattan's East Side.

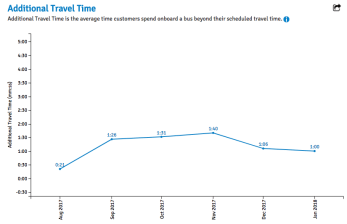

It’s a simple equation: A crosstown bus serving 28,000 riders travels four miles per hour. The route is hemorrhaging ridership, and the MTA has come up with a multi-faceted plan to change that: bus lanes, off-board fare collection, and the elimination of bus stops.

The MTA is getting an earful about that last one. On Monday, opponents turned out in numbers to present nearly 5,000 petition signatures to the MTA board calling for a local version of the M14 remain after the launch of the Select Bus express service, culminating weeks of agitation.

Buses and subways chief Andy Byford promised to listen, but emphasized his bottom-line: bus speeds.

“The reason we are having the debate about stops is because we are trying to speed up service,” he said. “We will try to come up with the best solution. What I’ve learned in 30 years of transit, though, is that you can’t please everyone.”

Last April, Byford unveiled his Bus Action Plan — since collapsed into the agency-wide Fast Forward plan — promising to rescue New York City’s ailing bus system, whose ridership has been dropping for almost two decades.

The plan is a multi-faceted approach: A new fare payment system will facilitate faster board at all door. Bus lanes and camera enforcement will keep private vehicles out of the way. Route redesigns will streamline routes and address the city’s over-saturation of bus stops.

But the fight over a few stops along the M14 highlights one of the great contradictions of the larger war to fix ineffective bus service in New York City and across the country. By eliminating closely spaced bus stops, transit agencies can facilitate faster trips, in turn attracting more riders. But doing so risks upsetting the existing customer base.

The primary route of the M14A and M14D is 14th Street — but both bus lines loop through the East Village, stopping 23 times. That’s a big reason why M14 buses spend 25 percent of the time at stops — and why the MTA is hoping to remove 12 of them [PDF].

Standing at one of the soon-to-be-eliminated stops on Avenue D and Ninth Street, Barry Robeson, 57, bemoaned the forthcoming changes. He lives further uptown, but comes to Alphabet City from the Union Square subway station to see the doctor.

The next-closest stop is 300 feet away, on 10th Street. If the Ninth Street stop had never existed, Robeson might have not even missed it, but it does exist — and he’s not happy to be losing it.

“I have osteo-arthritis, so I need the stop,” he said. “What about people like myself who have disabilities?”

Other crosstown buses simply go back and forth from the east and west sides, but M14 buses spend a large chunk of their time serving riders in the East Village and Lower East Side, essentially doubling as a neighborhood shuttle service. On weeknights, the eastbound bus remains packed as it turns off 14th Street, carrying riders from subway connections on 14th Street to the apartment complexes on the far-flung parts of the Lower East Side.

“This decision would make buses faster at the expense of serving the needs of residents in these neighborhoods,” Democratic District Leader Daisy Paez told MTA board members on Monday.

Paez and others have suggested that the MTA continue to operate local service alongside the express Select Bus Service — something Byford warned would lead to “bus jams.”

“We do understand that on the Lower East Side the so-called ‘granny route,’ i.e. the A and D, is heavily used by older people and people who may not be. able to walk so far,” Byford said. “We’re definitely okay with revisiting some of the stops, but if we put them all in, that will keep the service painfully slow.

“We’re trying to improve transit for the majority while still listening to communities, and getting that balance right.”

‘Separating emotions from math’

https://vimeo.com/240382367

The key to bus stop spacing, according to internationally renowned bus planner Jarrett Walker, is “separating the emotions from the math.”

The math is straightforward: Ridership tends to decline once walking distances exceed about 1,300 feet. To provide the fastest service to the most people with the least duplicate coverage, stops must be close enough to each other not exceed that distance, but far away enough to avoid excessive coverage.

In the Alphabet City section of the M14A/D route, bus stops are as little as 400 feet apart.

“A good bus stop is designed around the needs of a huge number of people,” Walker told Streetsblog earlier this month.

“When you start running the numbers on the effect on people’s travel time, even if they have to walk an extra block, it becomes impossible to argue that the extremely close stop spacing which you have now in Alphabet City, is the most effective policy. Getting people to gather at fewer stops makes the service faster.”

It’s not just an Alphabet City problem. In Europe, the standard calls for stops that are 2,100 1,500 feet apart. The MTA’s standard distance is a mere 750 feet — and that standard is rarely followed: In Manhattan and Brooklyn, the average distance between stops is 757 feet and 778 feet, respectively, according to a 2017 report by Comptroller Scott Stringer.

Brooklyn and Manhattan are the epicenter of the city’s bus crisis, having witnessed massive declines in ridership in the last five years. With 28,000 daily riders, the M14A/D counts among Manhattan’s busiest routes even as it loses riders along with the rest of the borough.

By removing 12 stops — seven from the M14A and five from the M14D — the MTA will bring the typical distance between stops in the Alphabet City to around 1,000 feet, or the distance between the crosstown blocks on the 14th Street segment of the route.

The agency points to the impact of its 2018 redesign of the Staten Island-to-Manhattan express bus network, which reduced the average number of times buses stopped before leaving Staten Island from 27 to 19. That produced a 12 percent increase in bus speeds.

Across the city, bus stop are too close together because the agency has spent years planning service for only the most dependent riders: seniors, the disabled, and the poor. Because of the needs of seniors and people with disabilities, in particular, the MTA and its sister agencies across the country dolled out bus stops like candy — and were loath to remove them.

Staten Island Borough President Jimmy Oddo probably put it best in 2017, as he set out to redesign his borough’s express bus network: “Who doesn’t want to give Mrs. McGillicuddy a bus stop?”

A nationwide issue

The battle around the M14 isn’t the MTA’s first go-around with bus stop reductions, and it won’t be its last. The Staten Island express bus network redesign incorporated the removal of stops, many of which were returned after rider complaints. And the forthcoming Bronx and Queens network redesigns will also undoubtedly include stop eliminations.

A majority of bus riders surveyed ahead of the Bronx redesign preferred faster service over frequent stops, but riders who lose stops will still emerge to complain once the redesign goes into effect.

Experiences in other cities show that a borough-wide approach may avoid public handwringing of the sort the MTA has faced in the East Village. In Richmond, Vir., for example, the city council passed legislation authorizing a citywide bus network redesign, which explicitly included wider stop spacing. That made the removal of specific stop more digestible for riders.

“It doesn’t get rid of all the mashing of teeth, and people screaming about [fairness], but it makes it much easier for everyone to see that, yes, taking this stop out and all the others has a really big benefit,” said Scudder Wagg, a consultant who worked on the Richmond project. “If you take it to the level of the whole system or the whole borough, you can show much greater benefits for the whole system, for an enormous amount of people, that it tends to break logjams … because you can show the benefits for many more people.”

The network redesign ended up eliminating 12 percent of the bus stops in the system. In practice, that meant five percent fewer homes within a quarter-mile of a stop, but a two percent increase in homes with a half-mile. In Staten Island, the loudest complainers with the most access were more likely to stave off bus stop elimination, according to one former MTA staffer who worked on the project.

“It’s a certain demographic of people. Certain neighborhoods would get stops restored and certain wouldn’t,” the staffer said. “What sucks is [that there are]people for whom it really is an extra hardship.”

Transit Center researcher Philip Miatkowski recently surveyed nine different staffers from nine different agencies at different points of the stop spacing reevaluation process, and is writing a report evaluating and comparing their methods. Survey participants were split on whether they preferred to eliminate stops citywide or route-by-route.

Cincinnati Metro, which is still early in the process, has opted to do a citywide marketing blitz even as it only makes changes on a few lines.

But that can have its pitfalls. Namely, it can have the adverse effect of drawing out concerns and complaints from people who rarely, if ever, ride transit. In the Seattle region, King County Metro began its efforts with a large media blitz, but eventually changed course.

“It was really gutting up their time and resources,” Miatkowski said of the outreach effort. “They really only want to hear … legitimate reasons to keep a stop. They felt that because they did a media blitz, they were getting all these excessive complaints that were taking up their time.”

King Country Metro has, along with the city of San Francisco, taken the proactive step of stationing bus “ambassadors” at eliminated stops along changing routes. Those ambassadors hear and respond to rider concerns directly, in multiple languages, and are available to walk riders to the next-closest stop, showing them that the extra walk isn’t all that bad.

Ultimately, politicians and community organizations must be brought on board early, according to Miatkowski.

“People in elected office rarely ride transit, and they only hear the negative parts — like, ‘Hey, my bus stop got moved!’” he said. “Most people don’t see the benefits because they don’t ride transit.”

This is the latest in a new Streetsblog series called “Best Practices,” which aims to provide New York State and City policymakers with examples of how their counterparts elsewhere have solved problems and made their communities more livable. The series is archived here.