Community Boards: The Roadblock to Safer Streets

DOT has held back installing many safety improvements due to parking and other car-culture gripes from out-of-touch community board members.

If you’re wondering why your street doesn’t have a bike lane, you might want to check with your local community board.

Chances are these local leaders — appointed by elected officials to represent their neighbors on zoning, traffic, and other close-to-home issues — have stood in the way of making your neighborhood streets safer for people walking and biking.

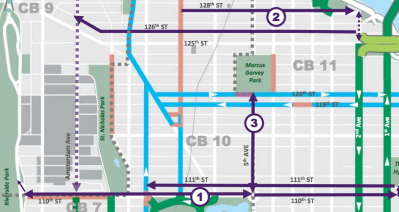

Take the recent example of Manhattan Community Board 9, which has held up the implementation of traffic-calming and painted bike lanes on upper Amsterdam Avenue for two years. In the time since, New Yorkers have continued to be injured or killed on the stretch — including Erica Imbasciani, 26, killed by a drugged driver last Friday.

Speaking to reporters Tuesday morning, CB 9 leaders doubled down on their opposition to the project, which would remove a lane of car travel, but also add turning bays to speed up traffic. Board leadership refutes that assessments, insisting that DOT’s efforts will slow down cars.

“You’re… removing a lane. And that’s what we don’t want,” CB 9 Transportation Committee Chair Carolyn Thompson told DOT officials in December 2017. (Thompson has also said she does not believe city and Census data showing that roughly 80 percent of the households in her district do not have a car.)

Municipal law requires only that DOT notify boards of redesign plans; the city is not required to oblige the whims of community boards on life-saving street changes. On many occasions, in fact, it has defied them: On Skillman and 43rd avenues in Sunnyside and Woodside last year, as well as on the second phase of its ongoing Queens Boulevard redesign.

Those decisions were made by Mayor de Blasio, however, and only after months of back-and-forth with local community boards whose members likely never intended to support DOT’s redesign efforts.

In the case of the Skillman/43rd protected bike lanes, DOT officials endured months of community board meetings, town halls, workshops, and behind-the-scenes confabs despite the leadership of Queens CB 2’s repeated statements against the project. The eight-month process only served to buoy DOT’s case to the mayor that it had done the satisfactory amount community outreach to move forward.

In other cases, DOT has totally acquiesced to community board concerns. Take the painted bike lane the proposed for Franklin Avenue south of Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn. The redesign did not remove any parking or travel lanes, but the agency nixed the bike lane in favor of extra-wide parking lanes at the behest of Brooklyn CB 9.

DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg has defended the de Blasio administration’s community board practices, while conceding that the back-and-forth slows progress towards safer streets.

“It’s a great forum to bring projects, to hear community concerns, to find people who care deeply about their neighborhoods, to get local input,” Trottenberg said in 2015. “We don’t agree 100 percent of the time.”

Meanwhile, a number of safety redesigns remain captive in the community board process — with lives like Imbasciani’s hanging in the balance. Council Member Antonio Reynoso has been particularly harsh towards DOT’s consensus-building effort, scolding Trottenberg at a public hearing last year for allowing community boards to “dictate how and when bike lanes should be built based on anecdotes and personal experiences instead of expertise.”

“No more community board conversations,” Reynoso added. “Use safety to dictate exactly what you should be doing. It’s frustrating. … You always go to these community boards, and council members give you trouble. Just stop coming to us and build them where you think they are appropriate. The Police Department would never ask a community board for permission to operate in a building if they thought drugs were being sold there. No, they just do the work because they think it’s appropriate.”

In that case and the cases listed below, the community boards’ opposition to safety improvements was based on the narrow concerns of drivers, who represent a minority of New Yorkers.

“Anecdotes and personal experience dominate decision making in community boards, not data,” Reynoso told Streetsblog in October. “There are folks that sit on transportation committee[s] that have no idea about transportation policy or any experience with it. Their background is that they care about parking.”

Here are other projects besides Amsterdam Avenue that are stuck in community board purgatory:

Queens Boulevard

DOT’s safety overhaul of the former “Boulevard of Death” — arguably the iconic redesign of de Blasio’s Vision Zero initiative — has stalled east of Yellowstone Boulevard, where it is caught up in the battle over the city’s plan to build a new jail in nearby Kew Gardens, Gothamist reported last week. The opposition centers around concerns from beleaguered small business owners mistakenly attributing their struggles to a lack of parking.

Dyckman Street

In Inwood, the future of protected bike lanes on the main east-west corridor remains uncertain seven months after Mayor de Blasio’s DOT nixed them on one side of the street after pressure from the local community board, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, and Rep. Adriano Espaillat. Opponents specifically said they don’t like the bike lane because it makes it harder for drivers to double-park.

Flushing

And in Flushing, DOT is planning months of outreach, including with Queens CB 7, before installing simple painted bike lanes. That plan is already facing opposition from board members.

“You can’t be serious with all of the truck traffic and parking that the hospital needs because they park all over our neighborhood,” CB 7 member Kim Ohanian reportedly told DOT officials earlier this month. “I’m sorry but I cannot and will not ever support this plan, you’re planning on putting a bike lane on my street in front of my house.”

Church Ave. and Ocean Parkway

Just south of Prospect Park, Brooklyn Community Board 12 has so far refused to endorse safety plans for the deadly intersection of Church Avenue and Ocean Parkway.

Unsurprisingly, their inaction has had consequences: On March 25, a 63-year-old pedestrian was injured and hospitalized after being struck there, Bklyner reported.