DOT Seeks Better Designs for Intersections

"Offset crossings," which the city piloted last year, may become more common on the city's protected bike lane routes.

You may be safer than you think.

A city intersection design that’s much reviled by cyclists because it forces them out of protected lanes and into a “mixing zone” with fast-moving cars remains one of the safest ways to deal with crossroads, a new Department of Transportation study reveals.

At the same time, a promising, Dutch-inspired intersection design that cyclists feel more comfortable about has flaws that will require tweaks before being rolled out widely, the city also discovered.

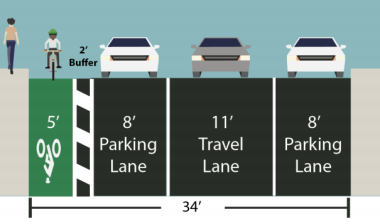

It’s all part of “Cycling at a Crossroads” [PDF], a detailed analysis of intersections of car lanes and protected bike paths, a persistent challenge for planners. Certainly, protected bike lanes have proven to be a life-saver all over the city — so safe, in fact, that almost all of the entire remaining safety challenge for them is at intersections, where 97 percent of collisions occur.

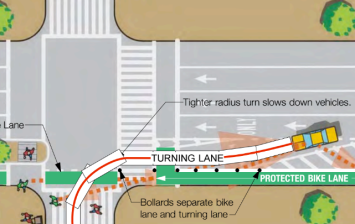

The study is part of an effort by the DOT to fix that problem — an initiative that dates back to April, 2017, when a truck driver turned into and killed 31-year-old Kelly Hurley, as she cycled in the First Avenue protected lane. After that death, DOT created something called “offset crossings,” a type of semi-protected intersection, and installed them at West 70th Street and Columbus Avenue and West 85th Street and Amsterdam Avenue.

Such intersections seek to reduce conflict between motorists and cyclists by forcing drivers to slow down to make a sharp turn that puts passing bike riders directly in front of them rather than over their left shoulders.

“We’re trying to give [cyclists] more precedent,” DOT Bicycle and Greenway Program Director Ted Wright said of the Dutch-styled design. “We’re treating them like pedestrians.”

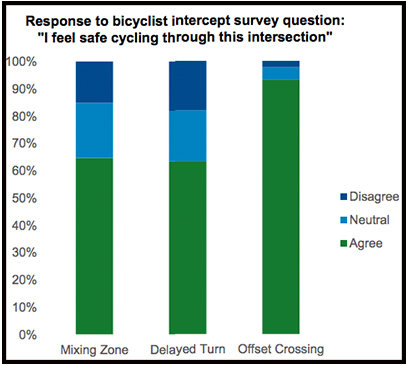

The DOT says that 93 percent of cyclists feel comfortable in such intersections — versus 65 percent at “mixing zone” intersections — but the study revealed flaws in the design.

For one thing, “Drivers are turning at a higher speed than preferred leading to short reaction times and more potential crashes,” the report says.

Also important: the design seems to be tricking bicyclists into thinking they must yield to the driver.

“This is likely related to the short reaction time, where bicyclists are unsure whether a driver will yield to them and thus make a cautionary stop,” the report says. “It is also not designed to allow for bicyclists to go behind the turning vehicle, the typical movement at mixing zones, likely increasing the number of bicyclists stopping for turning traffic.”

Such intersections will likely be tweaked before they are rolled out widely, the report says.

In the meantime, the study suggests that DOT continue to improve mixing zone intersections, which requires cyclists and drivers to navigate shared space. Many cyclists say they feel terrified in mixing zones — and such intersections had the highest rate of serious conflicts between drivers and cyclists, who sometimes go straight and sometimes veer around cars — but statistics show they have become safer in some key ways.

DOT has started shrinking the size of the mixing zone itself, and partly as a result, mixing zones have 30 percent fewer cyclist injuries than an intersection design called “fully split phase” — which gives cyclists and drivers their own red, yellow and green signals.

“The higher crash rate at fully split phase locations may be partially explained by risky behavioral issues such as red-light running [when drivers have the green light],” the report said. Also, this particular design is often used at higher-risk locations — where mixing zones might perform even worse.

In addition to offset design, the DOT has another pilot effort called “delayed turn” that gives cyclists a head start with a green light, but then gives turning drivers a blinking yellow. This design shows promise, but …

“Overall, the conflict rate between turning vehicles and bicycles is the lowest of the four treatments,” the report said, “but … conflict at the start of the flashing yellow arrow phase needs further evaluation.”

The biggest problem? No matter what intersection design, large majorities of cyclists in protected bike lanes say they don’t know which vehicle has the right of way at intersections. In a mixing zone, only 36 percent of cyclists said they knew who must yield. In an offset crossing, that rises to 42 percent — still far too low for DOT comfort.

(Hint: the turning vehicle must always wait for the cyclist going straight — but many drivers don’t yield, causing conflicts.)

“You have an inherent conflict where you have a vehicle [the bike] going straight, and vehicle [the car] making a right turn around that other vehicle,” Wright said. “All this stuff here — the massive amount of information that’s in this report — can be broken down to solving that riddle.”

— with Gersh Kuntzman