All Eyes on Van Bramer After Town Hall on Sunnyside Protected Bike Lanes

DOT held a town hall on the protected bike lane plan for Skillman and 43rd avenues in Sunnyside last night, and after much testimony, the key question remains the same: Will Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer support this critical street safety project for his district?

Van Bramer called for a redesign last year after a driver struck and killed Gelacio Reyes as he biked home from work at 43rd Avenue and 39th Street. But when DOT put forward a plan to protect people biking on 43rd and Skillman, local merchants complained about the conversion of curbside parking to make room for the bike lanes, and Van Bramer said he didn’t support the project.

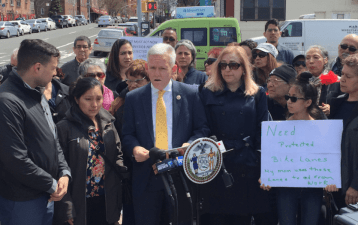

A year ago, Van Bramer stood with Reyes’s widow, Flor Jimenez, to demand the city make 43rd Avenue “safe for every single New Yorker, every single moment of every single day,” specifically with protected bike lanes. Protected bikeways on 43rd and Skillman would provide a safer bike route to and from the Queensboro Bridge for thousands of Queens residents.

At the town hall yesterday, Jimenez addressed the crowd of about 300 people, speaking in Spanish with the help of a translator. Fighting back tears, she urged the city to redesign the streets for safety.

“If something can be done, please do it, so there are no more families left as we are now,” she said.

DOT has adjusted its plan since November, mainly to appease the cantankerous merchants by repurposing fewer curbside parking spaces [PDF]. Some of those changes will also result in a safer design — at a few intersections, for instance, the plan now calls for DOT’s new bikeway intersection treatments (the agency calls them “off-set crossings”) instead of mixing zones.

The people who were opposed to the project before, however, remained opposed.

“Our concerns have not changed from the proposal that was presented in December,” said Gary O’Neill, owner of the Aubergine Café on Skillman. “Protected bike lanes do not guarantee safer streets, but it will mean a loss of business. The only guarantee with a protected bike lane is a loss of parking, not just for businesses but for the community as a whole.”

O’Neill is wrong on a few counts. The safety record of protected bike lanes is unambiguously positive, with reductions in traffic injuries averaging 20 percent after implementation.

There is no evidence, meanwhile, that claiming a few parking spaces to make walking and biking safer is detrimental to local merchants. New York has been implementing protected bike lanes on commercial streets for more than a decade. There are always some skittish merchants like O’Neill, but retail activity on streets like Kent Avenue in Brooklyn and Columbus Avenue in Manhattan continues to flourish.

Other attendees were convinced the plan would be a net benefit. Anna Thea Bridge, who lives on Skillman and owns a car, was won over by the shorter crossing distances for pedestrians. “I came here very much on the fence, without an agenda,” said Anna Thea Bridge, who lives on Skillman and owns a car. “This is compelling — the idea of having to get 28 feet across as opposed to 44.”

Orlando Gonzalez, who also lives in the neighborhood and owns a car, said that even though “parking is a pain, no doubt,” he has more pressing priorities. Gonzalez wants the redesign so he can feel safe carrying his child on his bike. “When I’m by myself, I weave in and out of traffic, and I bypass the double-parked cars,” he said. “But when I’m [biking] with my son in the back, the bicycle becomes a lot heavier. It’s harder to move, and it’s just awfully scary.”

All eyes are now on Van Bramer, whose support could make the redesign a reality. At the end of the town hall, he told the audience he remained undecided. “Nothing is a done deal, this is a proposal,” he said. “I listened to every single word that every single person said here today.”