It’s Not Your Imagination: The MTA Runs Less Subway Service Than It Did 10 Years Ago

Subway service today is atrocious, that much is clear. During rush hours, crowding and delays have reached crisis proportions, and off-peak, the wait for a train can seem interminable.

There are a number of culprits, including the failure to adequately maintain and upgrade track and signals, and the profusion of unnecessary timers slowing down trains. But one simple factor doesn’t get mentioned enough: During off-peak hours, the MTA doesn’t run as many trains as it used to.

The service reductions mainly stem from the financial crisis of 2008, when MTA revenues nosedived. While Albany enacted an MTA funding package in 2009 to prevent a total collapse of service, the agency balanced its budget with a round of deep service cuts in 2010.

For subways, the cuts mainly affected off-peak service. It’s a logical way to allocate resources when budgets are tight, but those times are also when subway ridership has recently seen significant growth. Off-peak service still hasn’t been restored to its former levels, so more people are riding the subway at times when the MTA is running less service than it provided 10 years ago.

These service cuts are especially painful for people who work outside conventional office hours, including New Yorkers doing shifts on nights and weekends. Let’s look at a few examples to see how these systemwide service cuts have contributed to the diminished utility of the system.

Back in 2008, the midday A train came as frequently as every six minutes during on weekdays. Similarly, on Saturdays, going northbound, service every eight minutes began at 6:30 a.m. and lasted until about 5:30 p.m. That’s 11 hours of frequent, useful A service. On Sundays, too, the MTA delivered, with trains running every eight minutes in the late afternoons, getting people home promptly before the week began again.

Today, during weekday midday hours, the A runs a measly seven or so trains per hour — once every nine minutes. On Saturdays, the window of eight-minute headways lasts about nine hours, not 11. And on Sundays, service every 10 minutes is as good as it gets. Keep in mind that the A splits in two at Rockaway Boulevard, so what may be barely-adequate on the main line equates to 20-minute headways on the branches to Lefferts Boulevard and the Rockaways.

On the R, weekend trains ran every eight minutes for 10 hours on Saturday, and six of Sunday in 2008. But today, the line runs no more than every 10 minutes on the weekends.

Most disturbing is the J. The 2008 version of J train service often arrived every eight minutes during off-peak hours. Today, the only time the J arrives more frequently than once every 10 minutes is during the weekday rush.

This is just a sample of the service reductions. While the MTA has restored some of the service cut in 2010, especially rush-hour service, off-peak service on most if not all subway lines remains below the level of 10 years ago. It has become the new normal.

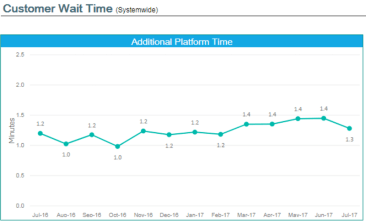

More recently, other service reductions have been forced by weekend work. The MTA’s flagging rules (which govern train operation while workers are on the tracks) mandate that all operators begin slowing to 10 mph as much as a quarter mile before a work zone. This reduces track capacity significantly, and if the MTA predicts that a line will be facing these changes more regularly — for example, on Queens Boulevard, where work upgrading the signal system is underway — the agency may preemptively cut service.

These cuts could be mitigated if the MTA was open to adjusting service patterns during longer-term projects. But instead of embracing flexibility, the agency is content with a status quo in which construction work detracts from service quality more than it has to.

In most cases, bringing scheduled service back to the levels of 2008 doesn’t even raise questions of how to juggle maintenance needs and subway frequency. It’s just a matter of allocating resources.

Yet when restoring cut services is brought up, the MTA often cites a lack of demand to justify doing nothing. This ignores perhaps the most basic truth of transit — that people do not flock to infrequent services. It also ignores history: Until recently, the MTA did run off-peak trains more frequently. If that was good for New York in 2008, why isn’t it good for New York in 2018, when more people ride off-peak?

Some of the problems plaguing New York’s transit system are entrenched and complex and will take some time to fix. Restoring off-peak service to 2008 levels isn’t one of those problems. Reversing these service cuts wherever possible would do wonders for system utility and perception. This is New York, where every minute counts.