How to Get New York Regional Rail Right

A through-running regional rail system for greater New York can help hundreds of thousands of people each day. When mapping out how to deliver that with new infrastructure, we need to get the details right.

The Regional Plan Association’s recently released Fourth Regional Plan calls for massive investment in greater New York’s transit infrastructure, including multiple regional rail tunnels. Has RPA mapped out a vision for regional rail that should guide New York and New Jersey for the next few decades? Yes and no.

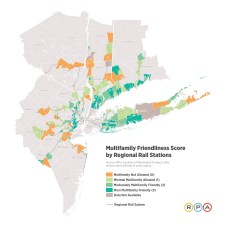

The RPA’s core concept is to unify the region’s three commuter rail systems — the LIRR, Metro-North, and New Jersey Transit — with through-running service making new transit trips possible. Northern New Jersey residents, for instance, would have seamless service through Manhattan to Long Island or Connecticut, rather than terminating at Penn Station.

Broadly speaking, this is exactly what long-term regional transit planning should aim for, but the Fourth Plan’s specifics are lacking.

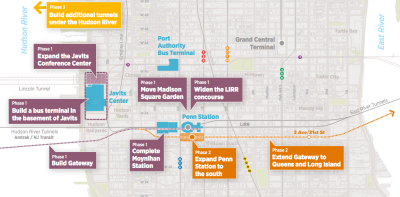

Building on the proposed Gateway tunnel between New Jersey and Penn Station, which the region’s political leadership firmly supports, RPA maps out two trunk lines through Manhattan, going east-west (under 31st Street) and north-south (under Third Avenue), with a station at the intersection:

Looking at the market for regional rail and how new infrastructure can accommodate it, there’s a better way to deliver a useful through-running network — with better service at less cost. Here’s how.

The Market for Through-Running

Subways and buses will always be the most important types of transit in the New York region, since most people either work in Manhattan or in their home county. But through-running regional rail could still serve a large number of people who don’t get much use out of existing commuter rail service.

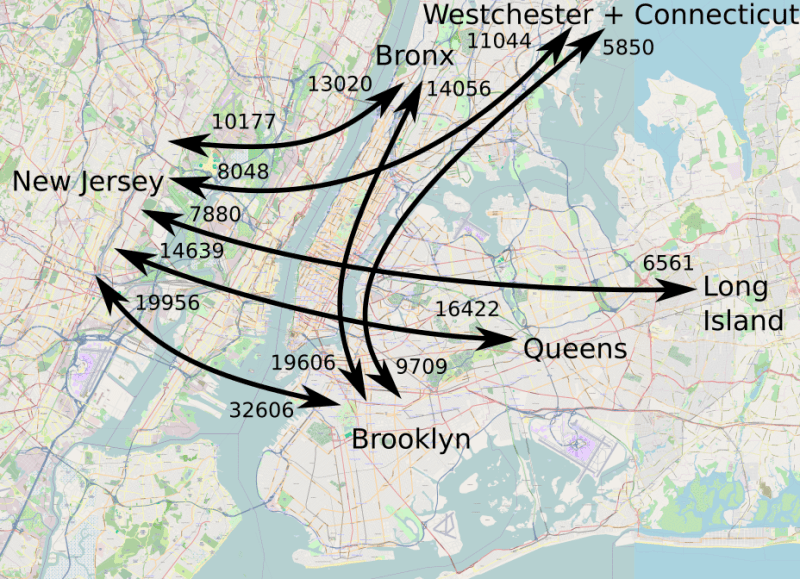

The Census Bureau has data on commuting between each pair of counties in the nation. Many commuters in the New York region pass through Manhattan and would be well-served by a seamless regional rail network (shown at the top of this post). For example, 32,606 people live in New Jersey or Rockland County and work in Brooklyn.

These travel markets combined have about 190,000 daily commuters who make 380,000 one-way trips each weekday. Currently, the total combined weekday ridership on the region’s three commuter rail systems is about 800,000, so this represents a potential 50 percent increase in ridership, before factoring in new development around stations.

Not all of these travel markets are equally strong candidates for regional rail. Between New Jersey and the Bronx, the Cross-Bronx Expressway is faster than trains through Manhattan could be. But some are very strong: Regional rail connecting to the downtown Brooklyn business district is likely to capture close to 100 percent of the current travel volume, plus additional trips as areas around suburban stations are developed.

How to Connect the Suburbs and the Outer Boroughs

Of the entire market for through-running regional rail, 43 percent of trips start or end in Brooklyn. This means that just running trains from New Jersey to Long Island and Metro-North territory is not enough.

Today, the only commuter rail service to Brooklyn comes from the east on the LIRR. To realize the potential of regional rail, new tunnels are needed, in addition to Gateway, with special attention to Brooklyn.

Based on expected travel volumes, I propose the following service map:

In this service map, there isn’t a one-seat ride between every pair of counties outside of Manhattan. That’s fine: There are still convenient connections from Long Island to Newark, or from Westchester to Brooklyn, which would involve cross-platform transfers at new stations in Sunnyside or Lower Manhattan. The single largest travel market benefiting from through-running, between Brooklyn and northern New Jersey, gets a one-seat ride, or a two-seat ride with a change at Secaucus.

This plan depends on three new underwater tunnels: the Gateway tunnel with a connection to Grand Central, a tunnel under the Hudson connecting Lower Manhattan with Jersey City, and one under the East River connecting Lower Manhattan with Brooklyn.

The RPA plan offers similar service quality, with one-seat rides to Brooklyn from Westchester, though not from New Jersey, whose commuters would need to make a cross-platform transfer in Manhattan. But it involves five new underwater tunnels — one more under the Hudson and one more under the East River than the map above.

(The map also includes a controversial tunnel to Staten Island, which is home to 49,000 Manhattan-bound commuters and 29,000 Brooklyn-bound ones. For the purposes of discussing through-running service, this tunnel can be ignored — it’s an expansion that is not necessary to the core network.)

Why Penn Station and Grand Central Should Be Connected

Missing from the Fourth Plan is a direct connection between Penn Station and Grand Central, which remains technically feasible and could enable through-running services without building as much tunnel mileage as RPA calls for.

Tracks linking Penn Station and Grand Central would also put two centrally located stations on the same line. This adds significant value because it gives commuters a choice.

Two projects already in the works are based on this value proposition: East Side Access is going to offer Long Islanders a choice between Penn Station and Grand Central, and Penn Station Access is going to do the same for Metro-North riders on the New Haven Line. A direct connection between the two major stations would also offer a choice to commuters in New Jersey and on the other Metro-North lines.

The more suburban commuters heading to Midtown have this choice, the better service will function, because peak loads will be more evenly distributed, as Montreal-based transit advocate Anton Dubrau has pointed out.

Right now, every full commuter train arriving at Penn Station or Grand Central has to completely empty, which crowds each station’s narrow platforms. With two stations, only half the passengers would get off at each, so trains would clear faster. This is only possible if the same train serves multiple city center stations.

Most successful regional rail systems have multiple stations in the center of the city for these reasons. In Paris, which should be the model for New York and other large cities, there are several central stops on each regional rail line, serving legacy train stations and business centers within the city. The same is true in other big cities with through-running service, such as Tokyo and Berlin. In the United States, Philadelphia’s through-running regional rail system has three central stops.

The Fourth Plan recognizes the need for multiple center city stations. However, RPA’s Midtown East station is at Third Avenue and 31st Street. Unlike Grand Central, this location is not within the peak employment area of Midtown and only connects to the 6 train (not the 4/5 express trains or the 7). As a result, most people would continue to disembark at Penn Station during rush hour, leading to the same platform crunches as today.

Getting the Details Right

There’s an extensive market within the New York region for through-running regional rail. The RPA’s Fourth Regional Plan recognizes this by calling for the integration of LIRR, Metro-North, and NJ Transit service. But the details of how to deliver that with new infrastructure need more work.

At rush hour today, full trains empty at Penn Station, crowding the platforms and passageways. A connection to Grand Central presents an opportunity not just to offer through-service, but to give passengers more choice about their Manhattan destination, and decongest Penn Station’s platforms in the bargain.