City Requests More Authority to Impose Safety Standards on Private Trash Haulers

The Business Integrity Commission says it lacks the legal power to enforce much-needed safety protocols for an industry with a deadly track record.

In the nine years Orrette Ewen worked for Sanitation Salvage Corp., a Bronx-based private hauling company, he was regularly forced to work 16-hour shifts, making up to 1,000 stops a night. He’d desperately try to stay awake behind the wheel, and sometimes have to drive trucks with shoddy brakes that he’d repeatedly warned his bosses about.

“It’s scary,” he said, following a City Council hearing about the private trash hauling industry. “It’s a scary situation knowing you could hurt someone.” (Management at Sanitation Salvage Corp. didn’t return a request for comment before publication.)

Sanitation Salvage is one of many carting companies that haul trash for New York City businesses. Oversight of the industry rests with the Business Integrity Commission. But BIC lacks the statutory authority to enforce safety protocols, agency officials said at Monday’s hearing — a situation they want council members to rectify.

Private carters haul garbage generated by offices, restaurants, retailers, and other businesses. All told there are 7,800 trucks in the industry’s fleet.

Their drivers have killed 43 New Yorkers since 2010, according to data released today. The number of deaths has varied between two and seven each year — including seven so far in 2017.

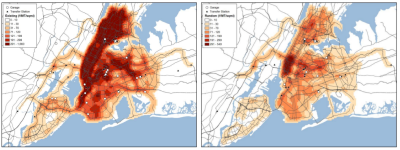

That’s much worse than the Department of Sanitation’s safety record. The city operates a fleet of about 5,500 sanitation trucks to haul residential waste, and DSNY drivers haven’t caused a fatality since 2014, officials said Monday. (One reason for the difference, according to DSNY, is that its routes are shorter — unlike private carters, which can send a single driver to cover a huge area, DSNY drivers cover limited geographic zones.)

BIC Chair Dan Brownell told lawmakers his agency is working on an industry-wide safety manual that will be released in the coming months, but that he lacks the authority to require companies to follow the new protocols. He asked lawmakers to craft legislation that would broaden BIC’s regulatory power.

“It is likely we will need mandatory measures in place to ensure that companies are actually using the materials and creating their own safety plans,” Brownell testified.

With that enabling legislation, BIC will be able to restrict the number of hours drivers can work a day, mandate safety training, and require companies to install side-guards, which can prevent pedestrians or cyclists from being run over by a truck’s rear wheels.

As it stands, Brownell said, the commission can’t even mandate the suspension of a driver who kills someone.

The current law grants the commission only “nebulous powers to establish standards for ‘compliance with health and safety measures,'” he said.

Brownell pointed out that when BIC was created 20 years ago, its main purpose was to run background checks to root out potential mob ties following a wave of criminal prosecutions.

Since 2015, BIC has shifted its focus to include traffic safety for the vehicles under its oversight umbrella, in sync with Mayor de Blasio’s Vision Zero initiative. Since then, the agency has regularly issued safety bulletins to all the private carting companies, revived a defunct advisory board to discuss safety issues, hosted symposiums, and offered financial incentives to companies who install side-guards on their trucks.

But so far private carters have taken BIC up on the offer to retrofit just 88 of the 7,800 trucks they collectively operate.

City Council Member Antonio Reynoso, who chairs the Sanitation Committee, said BIC has to do better and that its safety symposiums and email blasts amount to a “dog and pony show.”

“People are dying, things aren’t safe,” he said.

Reynoso said the council would consider expanding BIC’s safety oversight powers. He also noted that the city’s proposed zone collection system for private carters would cut down on truck traffic and make routes simpler, leading to safer streets, but that implementation is slated to take about six years.