A Whole Lhota Excuses About High MTA Construction Costs

New York is not the unique global case that apologists for excessive capital construction costs make it out to be.

New York City’s sky-high subway construction costs are finally getting some much-needed attention from elected officials. But with pressure mounting to reform MTA capital construction practices and bring costs down, the agency is falling back on familiar excuses.

Leading the call for reform are City Council members Ydanis Rodriguez and Helen Rosenthal, who have pressed for a commission to investigate the causes of MTA construction costs that routinely outstrip comparable costs in peer cities by multiples. In response, MTA Chair Joe Lhota sent a letter earlier this month to Rodriguez and Rosenthal detailing some explanations and reassuring them that the agency is already working on reducing costs.

Is Lhota’s response adequate? In short, no — his explanations and proposed solutions both fall flat.

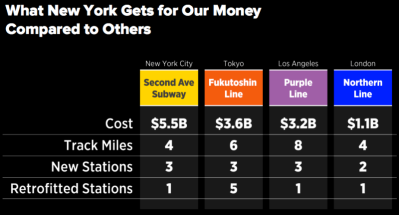

The fundamental issue at stake is that building subways in New York is several times costlier than in the rest of the world. The Second Avenue Subway and the 7 line extension to Hudson Yards cost around $1.5 billion per kilometer, and the LIRR’s East Side Access project (still in progress) is even costlier, about $4-5 billion. Meanwhile, the most expensive subway tunnel outside New York, London’s Crossrail, costs about $1 billion per kilometer, and the normal European range is $100-300 million. New York has a lot of explaining to do, and Lhota’s analysis doesn’t pass the smell test.

The biggest pushback I receive whenever I talk about New York’s high construction costs is always, “New York is special.” Much of Lhota’s response falls into that trap as well.

He talks about “fragile older buildings,” “aging and historic buildings,” and “the relative age of New York City’s utilities.” This does not explain why it costs more to dig in New York, on the Upper East Side, which was developed in the late 19th century, than in central London and Paris, in areas that urbanized in the late Middle Ages. It does not explain why the Second Avenue Subway costs 10 times as much as an under-construction line in Athens that brushes up against city walls built in antiquity.

Some of Lhota’s other explanations fall into the same “New York is special” category, on different dimensions: size and density. Lhota says that “high ridership imposes additional expense” because “our new stations need to be bigger.” But recently-built stations in Tokyo and London are bigger, and ones in Paris are almost as big. He says that New York has a high cost of land acquisition because its density is so high, but central London is more expensive than the Upper East Side could ever be.

Lhota does touch upon real issues confronting the MTA, but these are only partial explanations. He mentions, for instance, that 24/7 subway operations complicate track maintenance. This is indeed a cost driver that the city needs to find ways around. But it doesn’t explain the high cost of new subway lines, which are not built on active track.

For new tunnels, Lhota does offer one plausible factor: that the MTA needed to take particular care to avoid construction impact on Second Avenue by excavating the stations out of narrow holes. This is different than most subway construction today, which involves boring tunnels for the tracks while digging the stations out in the open (“cut-and-cover”).

To avoid street disruption, the Second Avenue Subway’s stations took much longer to build than if the MTA had used cut-and-cover. It’s a dubious tradeoff: while only about half the width of Second Avenue was taken at station sites, the disruptions lasted a lot longer than they would have otherwise. In the future, to reduce costs the MTA should use cut-and-cover to build stations.

But Lhota is not proposing cut-and-cover or other specific ways to save money. Instead, he is proposing more nebulous solutions. Some look like they could be useful, such as better investigation of underground utilities to reduce geotechnical surprises and curb cost overruns. But they don’t add up to making New York subway construction costs on par with Paris or any other European or Japanese city.

One of Lhota’s ideas might actually be counterproductive: “maximum use of ‘design-build'” procurement. While design-build has been credited with preventing overruns on projects like the Tappan Zee replacement bridge, the jury is still out.

The lowest tunneling costs in the world are in Spain. Madrid built subways around the turn of the millennium for $60 million per kilometer, and Madrid Metro’s then-CEO, Manuel Melis Maynar, wrote about how cities can maximize efficiency. He warned against design-build, arguing that contractors who were not involved in design would be more flexible and more willing to make small changes, which are inevitably necessary.

Unfortunately, the takeaway from Lhota’s letter is that MTA still seems indifferent to solving its capital cost problem. It is not plausible that the MTA is already doing everything it can to build efficiently — if that were the case, we would be seeing evidence of progress in the form of lower costs. While Lhota makes a handful of good points, they are buried beneath chaff that suggests the MTA’s leadership isn’t really interested in learning from the world’s best practices.