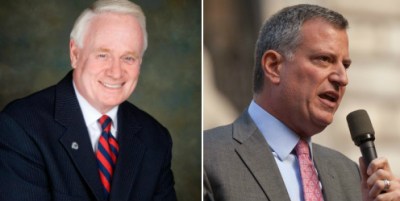

The Restoration of NYC Principal Parking Perks Reveals the Warped Priorities of Placard Culture

In a pair of Bloomberg-era decisions, an arbitrator and a judge agreed that school administrators were entitled to free parking on the job, and said taking transit to work was a hardship for DOE employees.

Siding with New York City school administrators who sued to retain their parking perks, an arbitrator and a judge agreed that free parking was a right enshrined in the principals’ union contract, and ruled that taking transit to work was unfair to Department of Education employees.

The 2009 and 2010 rulings, which City Hall sent in response to Streetsblog’s request for information on the de Blasio administration’s decision to issue tens of thousands of additional parking placards this year, speak to the biases of legal authorities who’ve made placard perks difficult to dislodge.

A little background: In 2008, Mayor Michael Bloomberg cut the number of DOE parking placards from 63,000 to around 11,000, aligning the number of permits with the number of on-street parking spots allocated to schools. The reforms were enacted to reduce traffic and illegal parking around school buildings. Under the old first-come, first-served system, permit holders who drove to work but couldn’t find a reserved school spot were free to park virtually anywhere without fear of being ticketed.

After some resistance, the United Federation of Teachers acknowledged the old system was broken and agreed to the reduction in placards. But the union that represents principals and other administrative staff, the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators, sued the city to get placards for its members reinstated. The Bloomberg administration proceeded to defend its placard policy in court.

The stalemate continued until this spring, when, as a result of “arbitration and negotiations,” the de Blasio administration agreed to reissue placards to CSA members as well as every other DOE employee who has a car and wants a permit.

City Hall would not explain whether its hand was forced or the placards were reissued voluntarily, so Streetsblog filed a FOIL request for records related to this decision. We’re still waiting, but the city has sent older documents from the CSA case.

A 2009 finding by arbitrator Ralph Berger [PDF] held that the placard reductions were in violation of the CSA’s collective bargaining agreement with DOE. The union claimed parking privileges were subject to contract negotiations, since “the availability of free parking for employees while at work is an economic benefit.”

Berger concurred, but his decision did not grapple with the monetary value of parking placards and how that could be replaced by other means, like a mode-neutral commuting benefit. (Union members who ride transit to work get tax-free MetroCards, a benefit worth far less than free guaranteed parking.)

Instead, Berger viewed parking placards as an irreplaceable benefit, and wrote that revoking them “constituted a significant and adverse alteration of … working conditions.”

Berger cited the case of Joseph Clausi, an assistant principal who testified that “when he had a parking permit, he arrived to work by 7 a.m. for a 7:25 a.m. start,” but that “without a parking permit, he has to arrive by 6:00 a.m. to find parking.”

To be sure, Berger based his ruling on several factors, but one of them was the belief that not having unfettered access to free parking was prima facie evidence of hardship. “The very fact that City parking spaces are so limited and sought after,” he wrote, “made it especially beneficial to have the opportunity to park in a free Department-designated spot.”

Here’s Berger referring to testimony from a CSA member who stopped driving to work:

Department Placement Officer Braulio Navarro testified that he has worked for the Department for nine years and that every year he has received a parking permit. The permit allowed him to park in on-street parking spaces designated for Department employees. Since the Department took away his permit, he now uses public transportation to commute to work. Navarro testified that it used to take him 40-45 minutes to drive to work, but “now it takes me about two and half hours, two hours” each way … He also stated that he had used the permit to park when he had meetings away from his office. Navarro now uses public transportation, or walks to get to these meetings. The walk can take him 45 minutes to an hour.

Without carte blanche parking privileges, in other words, Navarro joined the millions of New Yorkers who take transit to their jobs.

When the Bloomberg administration challenged Berger’s decision, CSA filed suit. In 2010, Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Joan A. Madden agreed with the arbitration award [PDF], rejecting the city’s counterclaim that Berger overstepped his authority and that the award violated a public policy.

Madden’s ruling also betrays a windshield bias. The judge cited precedent from a dispute between New York City Transit and TWU Local 100, which held that arbitrators violated public policy when they found fault with the authority’s policy of firing workers who violated safety rules.

“Here, the issue is not safety,” Madden wrote, “but the delegation of parking permits.”

But there is a compelling public interest in limiting parking placards, which increase traffic and congestion and are routinely abused in ways that do jeopardize people’s safety.

After the de Blasio administration increased the number of placards in circulation this year, tens of thousands of DOE employees are again competing for roughly 11,000 on-street spaces. Crosswalks, bus stops, no-standing zones, and other areas where parking is prohibited are again fair game for DOE staffers who can’t find a legal spot.

City Hall still owes New Yorkers a full explanation of why it allowed parking placards to proliferate again.