Step One Toward Fixing the Subway: Be Honest

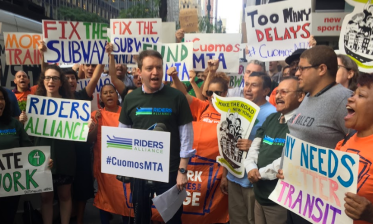

Governor Cuomo won't get far if the MTA isn't candid about the subway's problems and what it will take to fix them.

The New York City subway is not in good shape. High-profile breakdowns and a tangible increase in severe delays have brought widespread attention to years of decline in service levels. Train breakdowns are on the rise, and service is slowing down. After a long period of growth, subway ridership recently stalled and appears to be declining in 2017 despite the opening of the Second Avenue Subway.

The MTA has for the most part been running on autopilot. Senior management tries to avoid taking responsibility, and planners are afraid of doing or saying anything that would invite scrutiny from the media or their superiors.

This paralysis is accompanied and enabled by a lack of candor about what is going on. Some of the subway slowdowns involve slow orders on the tracks for maintenance, while others involve poor train maintenance. The MTA blames most delays on overcrowding, a claim that was uncritically parroted in the New York Times. But while crowding may be a problem, it has become a fallback excuse, cited whenever the MTA cannot identify another reason for a delay.

There are steps the agency could take to improve service relatively soon, but to make them happen, Governor Andrew Cuomo and his MTA CEO, Joe Lhota, will have to step in and put their authority at the MTA to good use. So far, however, they have done no such thing.

Cuomo wants to be perceived as taking action, so he recently declared a state of emergency, which according to one inside source at the agency has gotten MTA managers scrambling, but without any real purpose. That was preceded by his announcement of “genius” grants, judged by tech people who are mostly not in the transit field.

Lhota, for his part, was just appointed to the CEO position and has to catch up with the changes in New York’s transit situation since he left his first stint as MTA chief in 2013 to run for mayor. He’ll be getting up to speed while retaining his full-time job as an executive at NYU Langone.

What would it look like if Cuomo stopped making empty gestures and started exercising real leadership at the MTA? Here are three steps that, in the medium run, could make a difference for subway service.

First, Cuomo and Lhota should bring in outside experts for real, substantive transfers of knowledge, not the superficial stagecraft of last week’s event with the CEO of RATP, which runs the Paris Metro. Instead of one-time meetings and photo-ops, Cuomo and Lhota should hire people with experience running trains in large, complex subway systems, such as Tokyo or London, and give them space to study New York City Transit’s operations and make specific recommendations. This is likely to involve multiple people working together for a period of months before they can offer concrete suggestions for more efficient operations.

Second, they should declare speed a priority. The MTA has been too hasty to sacrifice service quality for dubious safety rationales. After two fatal crashes in the 1990s, the MTA installed signal timers to reduce train speed. But one crash had nothing to do with speed, and the other involved a train exceeding the speed limit. The MTA also has large and growing safety margins near work zones — stretches of track with slower speed limits. Some safety margins are necessary, but the MTA has gone too far, to the detriment of good service.

Third, instead of his flashy, tech-focused “genius” grants, Cuomo should have the MTA reevaluate routing and scheduling. The solution to a problem may involve a software fix, but it may just as well involve a change in where and when trains run. One option is pruning branches. New York is unique in how complex its subway branching is, and it should look into disentangling lines, even at the cost of removing some one-seat rides. Alternatively, the MTA could change the frequency guidelines to ensure trains that share tracks have the same frequency, even if one route ends up more crowded than the others, to maintain even headways. Having one line that comes every five minutes and another that comes every six minutes share tracks is a recipe for baking “ladies and gentlemen, we are being delayed because of train traffic ahead of us” into the timetable.

The thread tying these three solutions is honesty — honesty about the state of the system, about tradeoffs, and about the scale of effort required.

There is no silver bullet. But neither is the solution some grand undertaking requiring billions of dollars and a monument named after Cuomo. Everything on the above list should take months, not years.

Real tradeoffs will be necessary. It’s possible, for instance, that improving maintenance will require more extensive nighttime shutdowns than under today’s Fastrack initiative, which itself was controversial when it began in 2013. Lhota has indicated openness to this idea.

The changes may also lead to some pushback from the unions. Before he can make millions of New Yorkers less angry about the subway, Cuomo will probably have to make some people angrier. He’ll have to finally invest political capital in improving transit in New York.

Cuomo and Lhota have a choice: They can promise sexy quick fixes and cross their fingers that things will somehow work out (they won’t), or they can be honest with transit riders and get started on useful medium- and long-term solutions.