There’s Got to Be More to the L Train Shutdown Plan Than What the MTA and DOT Have Shown So Far

Replacement service won't work without dedicated busways on surface streets.

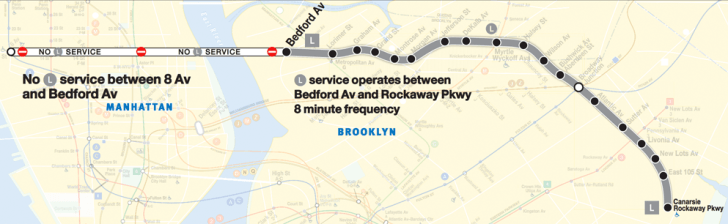

Starting in January 2019, service on the L train west of Bedford Avenue will be suspended for 15 months to allow for Sandy-related repairs. The only way to keep hundreds of thousands of people moving is to dedicate significant street space to buses on both sides of the East River. But at a presentation to elected officials on Friday, the MTA and DOT did not indicate that bus lanes are part of their plan, except on the Williamsburg Bridge itself.

There’s still time for the agencies to flesh out more transit-priority treatments for the L train outage, but the signs so far are troubling. In the Friday presentation, the MTA forecast that about 70 percent of the 275,000 daily L train trips affected by the shutdown will be diverted to other subway lines, with the rest relying on buses, bikes, car services, or ferries, DNAinfo reports.

For subway passengers throughout the city — not just L train riders — this should set off alarms. At a time when crowding-related train delays are reaching crisis levels, the MTA and DOT should be aiming to run fast, high-capacity bus services to attract displaced riders to the greatest extent possible and avoid placing unnecessary strain on the subways.

Several stations that L train riders would be expected to use instead are ill-equipped to handle an influx of riders, according to BRT Planning International’s Walter Hook. The 7 train advocacy group Access Queens has also noted that Long Island City’s Court Square station, where riders would be expected to transfer from the G to lines connecting to Manhattan, already suffers from bottlenecks and inadequate entryways [PDF].

The MTA and DOT presentation includes three shuttle bus routes: from Bedford Avenue to Bleecker Street, Grand Street to Bleecker Street, and Grand Street along First and Second Avenues to 14th Street. These routes are shorter than the ones advocates have proposed, but that could be for the best, since it will allow the MTA to run a given number of buses more frequently.

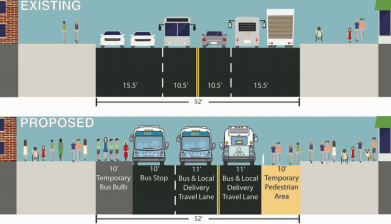

On the Williamsburg Bridge, one lane in each direction would be reserved for buses and trucks, and another two-way pair would be reserved for motor vehicles with at least three occupants. But the presentation did not mention any bus lanes elsewhere, according to Edward Baker, communications director for Assembly Member Joe Lentol, one of the elected officials briefed last week.

On-street busways are an essential part of any L train plan. Without dedicated, car-free space for buses on 14th Street and the streets approaching the Williamsburg Bridge, the new bus routes will get bogged down in traffic, speed and reliability will suffer, and fewer people will use them. Subways will get more crowded, traffic congestion will get worse, and people will end up making fewer trips.

That’s not lost on Lentol. “Assemblyman Lentol, throughout the planning process, has stressed the importance of having efficient shuttles, which would likely require dedicated bus lanes,” Baker said in an email to Streetsblog.

DOT and the MTA may still be working on the details of a plan for surface streets. A public proposal is expected this spring, followed by a final plan in the fall.

But given Mayor de Blasio’s tepid response to the L train situation so far (he’s emphasized ferries as a solution, but in a whole day the new ferry route linking Williamsburg to East 20th Street will carry about one train’s worth of passengers), as well as the MTA’s apparent hesitance to plan for high-capacity bus service, the omission of a transit-priority plan for surface streets in last week’s presentation is a distressing sign.