Whose Job Is It to Fix the MTA? 3 Reasons to Point Your Finger at Cuomo

Comptroller Scott Stringer came out with a big report yesterday about how New York City contributes more to the MTA than you might think. Add up all the fares, tolls, dedicated taxes, and public funding that originate from the city, and it comes out to $10.1 billion per year.

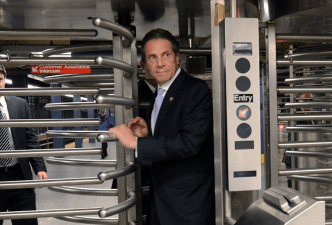

With Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio tussling over who should pony up and cover the massive hole in the MTA’s five-year capital plan, the Stringer report was taken to be a news cycle win for team de Blasio. The thing is, there are much better reasons to point your finger at Cuomo instead of the mayor.

The share of MTA revenue coming from NYC is actually about what you would expect, since, as Stringer’s report also points out, the MTA spends $9.86 billion annually on services and infrastructure benefitting New York City residents. There’s still about $270 million that flows from city sources to the commuter railroads serving the suburbs — and that’s an imbalance that should get fixed — but in general, the MTA budget isn’t broken because New York City pays more than its fair share.

It’s broken because there’s a huge hole in the capital program and the one person who can really do something about it — Cuomo — is sitting on his hands. (If the core problem was too much revenue coming from NYC, then the Move NY toll reform plan wouldn’t be much of a fix, since most of the revenue would come from New York City drivers. But Move NY is, of course, a stupendous improvement over the status quo, because it attacks the capital plan deficit while unclogging the city’s crippling traffic jams and speeding up buses.)

So yeah, lay the blame for MTA rot on Cuomo. But blame him for the right reasons…

1. It’s His Agency

The MTA is chartered by the state of New York. The chair of the authority serves at Governor Cuomo’s pleasure. Any major MTA policy decision made in opposition to Cuomo’s wishes is pretty much unthinkable.

2. Cuomo Controls the Money

The mayor of New York cannot negotiate contracts with the MTA’s labor unions, reach backroom deals to slash dedicated MTA revenue streams, sneak backdoor MTA budget raids into the state budget, or direct MTA capital construction managers to build stuff more efficiently. The governor can.

Yes, the mayor can cajole the MTA into building major projects using funds controlled by the city, like Bloomberg did with the 7 train extension, but that doesn’t mean the mayor has substantive power over the agency’s capital spending. If the mayor could dictate how the agency invests in its infrastructure, this monster never would have happened…

3. East Side Access

East Side Access is the new LIRR terminal under construction beneath Grand Central, and it’s the most expensive and time-consuming expansion project in the MTA capital plan. According to the latest estimates, it will cost $10.8 billion and wrap up some time in 2023, at least $6.5 billion over budget and 14 years behind schedule.

The primary beneficiaries of this huge public expense will be commuters from the Long Island suburbs who’ll get to make more direct trips to the office and back. But on Long Island, not-in-my-backyard resistance is obstructing efforts to expand the capacity of the LIRR Main Line and rezone areas near stations for more compact development — limiting the benefits of East Side Access. All the while, the island’s state legislators are waging a non-stop campaign to slash the MTA’s dedicated taxes coming from their districts.

Deciding which MTA construction projects get in the pipeline is, to a large extent, a political process, with four appointees wielding veto power over the capital program. The governor, the Assembly speaker, the State Senate majority leader, and the mayor of New York each control one vote. All four have some leverage, but the governor, with his power to reward or punish the two legislative leaders by steering deals in the state capitol, has the most. The mayor, who’s not part of the three-men-in-a-room gang and has to beg Albany for even the most innocuous policy changes, has the least.

So who should be shouldering the responsibility for seeing this $10 billion LIRR station through to completion — the governor or the mayor?

The State Should Act First

Both the state and the city used to contribute much more to the MTA capital program than they do today. In the eighties, it was Governor Mario Cuomo who initiated a rapid pullback in direct funding. The state went from contributing 20 percent of the MTA capital budget in 1983 to zero in 1992.

The city pulled back too. Even with de Blasio’s recent commitment to budget $657 million for the $32 billion plan over five years, the city won’t come close to the 9 percent contribution it used to make.

If the city and state both returned to the level of support in the 1980s that began to lift the transit system out of its downward spiral, the MTA would be much less reliant on debt, and straphangers would be much better off. For all the reasons listed above, though, the governor should be pressured to make the first move.

The MTA is not the mayor’s agency, and New York needs to know it has a good-faith partner in Albany before sticking its neck out. So far, Andrew Cuomo hasn’t shown any reason to believe that he’s a governor you can trust on transit.